My somewhat solipsistic entry point for these reflections on Machiavelli is an undergraduate paper that dates from 1977. The hastily written six-page paper argued, unoriginally, that Machiavelli adhered to two moral codes. These were Christian (or Judeo-Christian) morality and a civic morality, or a morality of the state, that could override Christian morality when the “necessity” of maintaining power, or the goal of political stability, demanded it. The graduate student teaching assistant who read and graded my paper was not persuaded; Machiavelli, in his view, rejected Christianity in favor of the civic virtues embodied in the ancient Roman republic. The grader commented in the margin: “If there are higher ends that surpass those of Christian morality doesn’t that constitute a rejection of the latter?”

I no longer think, if I ever did, that the question whether Machiavelli adhered to two conflicting moralities is particularly interesting. One might also question, of course, whether the “morality of the state,” however defined, is actually a thing, i.e., whether it’s a moral position at all.

However, my paper’s main flaw was that it neglected to discuss the key contextual element of The Prince, namely Machiavelli’s preoccupation with the difficulties faced by the “new prince,” the ruler who seizes power rather than inheriting it, or who comes to power via an alliance with a foreign state. Here Machiavelli likely had in mind the position of the Medici, newly restored to power in Florence in 1512, after eighteen years in exile, thanks to Spanish military force.[1] As J.G.A. Pocock observes, however, the level of abstraction in The Princeis such that “it is never possible to say exactly how far [it] is intended to illuminate the problems faced by the restored Medici in their government of Florence…. Il Principe…would seem to be…inspired by a specific situation but not directed at it.”[2]

Addressing the new ruler, Machiavelli warns him that “you [will] make enemies of all those whom you have injured in annexing a principality, yet you cannot retain the friendship of those who have helped you to become ruler, because you cannot satisfy them in the ways that they expect. Nor can you use strong medicine against them, since you have obligations to them.”[3] As Machiavelli’s generalizations and injunctions pile up, it becomes clear that “strong medicine” will likely have to be used against someone(or someones), albeit selectively and in a way not calculated to stir up hatred among the majority of the prince’s subjects. Nonetheless, “it is impossible for the new prince to escape a name for cruelty because new states are full of dangers.”[4]

Machiavelli peppers the new prince with a lot of advice: commit cruelties in one fell swoop rather than bit by bit; don’t use mercenaries; keep yourself fit and prepare for war by hunting; and so on. Probably the most famous advice is in Chapter 18, where Machiavelli tells the prince to be like both a fox and a lion, i.e. clever (or cunning) and strong, and not to rely on strength alone.

In that same chapter Machiavelli writes that the new prince “must be prepared to vary his conduct as the winds of fortune and changing circumstances constrain him and…not deviate from right conduct if possible, but be capable of entering upon the path of wrongdoing when this becomes necessary.”[5] The least sensational part of this sentence is the most significant: namely, the counsel to tack to the winds of fortune, where fortuna, in Pocock’s words, “symbolizes pure, uncontrolled, and unlegitimated contingency.”[6]

However, the recommended flexibility is extremely difficult to pursue: people tend to stick to modes of behavior that have worked well in the past or that they find naturally comfortable. “[O]ne does not find men who are so prudent that they are capable of being sufficiently flexible: either because our natural inclinations are too strong to permit us to change, or because, having always fared well by acting in a certain way, we do not think it a good idea to change our methods.”[7] Thus Chapter 18 gives advice that, according to Chapter 25, cannot be put into practice.

Whether the advice to adjust to circumstances can be followed or not, its source seems to lie in Machiavelli’s paramount concern with political stability[8]and with the question of how an innovator (Pocock’s word) can maintain power by securing his own legitimacy rather than relying on custom or tradition. Doubtless one reason for Machiavelli’s concern with stability is that his own life was directly affected by political turmoil. Moreover, he clearly deplored the relative weakness of most of the Italian city-states and their vulnerability to outside invasion. Hence The Prince’s concluding chapter, “Exhortation [to the Medici] to liberate Italy from the barbarian yoke.”

There are as many interpretations of Machiavelli as there are philosophical, historiographical, and methodological tendencies. I am not a Machiavelli scholar and thus not well positioned to anoint a favored interpretation. That said, I think it’s worth emphasizing that, like all books, The Princeis a product of a particular time and place. It may or may not be intended as a send-up of the mirror-of-princes genre of its day, but in any case it is not an advice book for CEOs, despite its occasional placement in the business section of bookstores, or a self-help tract. If you’re having trouble navigating your own winds of fortune, The Prince probably won’t help you. By all means read it – after all, how many books in the canon are this short? – but don’t go looking for something that isn’t there. That’s a recipe for disappointment.

________________

[1]See Quentin Skinner, Introduction to The Prince, ed. Q. Skinner and R. Price, Cambridge U.P., 1988, p.xii

[2]J.G.A. Pocock, The Machiavellian Moment, Princeton U.P., 1975, p.160

[3]The Prince, ed. Skinner and Price, p.7

[4]The Prince, trans. and ed. Harvey Mansfield, 2nd ed., U. Chicago P., 1998, p.66

[5]The Prince, ed. Skinner and Price, p.62

[6]Pocock, Machiavellian Moment, p.156

[7]The Prince, ed. Skinner and Price, p.86

[8]See Bernard Crick, Introduction to Machiavelli, The Discourses, Pelican Classics, 1970, p.22

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks to L.D. Burnett for posting this for me.

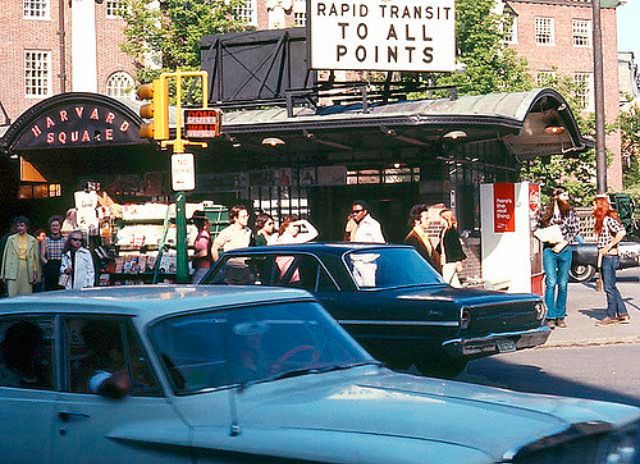

L.D. chose the accompanying photograph. I probably would have gone with a standard, boring head shot of Machiavelli, but being the editor of a blog has (and should have) its privileges.

P.s. The course in question was a large-ish lecture course on the Renaissance, Humanities 115 as it was styled in the catalog. My attention that semester was elsewhere, which probably explains why, if memory serves, I read The Prince and wrote the paper all in the space of a sleepless 36 hours or so. Well, it’s all water under the bridge (and if you don’t like that cliché, substitute another).

I read this with interest, Louis, thank you.

Thanks Anthony.

Louis, I couldn’t help but choose this picture, with that signage and the people beneath it, each one navigating with or against the winds of fortune. And I love the 1970s, visually, musically, historically. Such an under-rated decade.

Pocock discussed Machiavelli’s use of both cooking metaphors and navigation metaphors to describe how people deal with contingencies, and of course your title picks up on the latter usage.

It reminded me of George Gray’s epitaph from Spoon River:

I have studied many times

The marble which was chiseled for me–

A boat with a furled sail at rest in a harbor.

In truth it pictures not my destination

But my life.

For love was offered me and I shrank from its disillusionment;

Sorrow knocked at my door, but I was afraid;

Ambition called to me, but I dreaded the chances.

Yet all the while I hungered for meaning in my life.

And now I know that we must lift the sail

And catch the winds of destiny

Wherever they drive the boat.

To put meaning in one’s life may end in madness,

But life without meaning is the torture

Of restlessness and vague desire–

It is a boat longing for the sea and yet afraid.

I guess that was Edgar Lee Masters’s stab at the sentiment behind the line, “I have measured out my life in coffee spoons.” I suppose one could argue that Eliot’s poem is the better one technically. But you know me: I am happy enough with middlebrow bards.

Anyway, thanks again for writing this post.

…that signage and the people beneath it, each one navigating with or against the winds of fortune.

Of course, I get it now! I should have looked at the photo more closely. The models of the cars suggest that the photo is from the early part of the ’70s, not the latter part — but anyway, very appropriate.

Btw, for a post at my own (no longer active) blog a few years ago, I had occasion to do a little research on the reception of Machiavelli, esp. in the 16th and 17th centuries. The literature is large, but in case anyone’s interested one ref. is R. Bireley, The Counter-Reformation Prince (1990). There is also some, albeit more rambling, discussion in a couple of Foucault’s lectures (collected in Security, Territory, Population, one of the translated vols. of his Collège de France lectures).

In case anyone wants to know what to read about M. in an introductory way, one might start with the entry, and good bibliography, on Machiavelli at the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. And also see some of the works Matt Crow mentioned in the previous comment thread.

Jacob Soll’s Publishing the Prince is another great reception study of Machiavelli.

Thanks, Louis–I learned a lot from this as it has been a while since I read The Prince. I was struck by your final point–that The Prince ought not to be mischaracterized as a business self-help book–and by the use of the word “innovator,” which as you pointed out, is Pocock’s term. That word immediately connected for me with Clayton Christensen’s idea of disruption from his book The Innovator’s Dilemma, which surely someone has called “a modern-day Prince.”

If it’s absolutely true that The Prince is not a business self-help guide, it might still be the case that the connection exists going the other direction: just as with Sun Tzu, hundreds of writers for business have thought of their books or articles as existing “in the tradition of” or as an updating of these classic (but not business-oriented) texts. While their appropriations may not be reliable (or even plausible), perhaps it is still not so easy to disentangle them?

Andy,

Yes, I think your point about the connections/appropriations is spot on.