Earlier this summer, I wrote about the transcript of a talk I read called “Coming of Age at the End of the World: Eco-Grief, Affective Resilience, and The Climate Generation.” The talk was given by Sarah J. Ray, a professor at Humboldt State University and the coordinator of its Environmental Studies Program. Ray’s narrative turned on this realization: a number of her students, highly idealistic, having moved through the ES curriculum and come to grips with the depth of the climate problem, were showing up in her office, feeling hopeless and paralyzed. Some were breaking down in tears. This was happening so often that she made the phenomenon the focus of her research. How to understand it? How to develop ways to deal with it in the classroom?

In my post, I explored the concept of climate trauma but only mentioned in passing the part of Ray’s talk that concerned practical application. Her investigation of these matters had included studies in the psychology of education from a number of perspectives. “What do these educational psychology worlds tell us?” she asked. “They tell us that emotions are central to student success, centering emotions is a matter of educational equity and inclusion, and the emotions of collected efficacy, pride, and desire for the future are necessary for cultivating resistance.”

The centrality of emotions, educational equity and inclusion, the cultivation of resistance—Ray’s remarks hit home.

I don’t currently teach environmental studies–I teach the US History survey, mostly. But US History is an emotion-evoking course, and maybe even, for some, traumatic. “Students need to know their history,” I’ve often heard it said, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to be pleasant. History students who have identified with American ethno-nationalism may be irritated by feelings of guilt and may react defensively. Students of color and others who’ve been othered by that same ethno-nationalism may feel angry or humiliated or have a sense of bitterness renewed. No matter how hard one might strive, in accordance with the scientific method, to take a position of disinterest, it’s hard not to feel history personally when that history is one’s own.

Some students, I gather, are very verbal about their emotional needs and responses–requesting trigger alerts and calling for safe spaces and whatnot. My students aren’t making those requests (not that I’ve informed them of the option). They stay pretty tight-lipped most of the time. I tend to chalk this up to ill-preparedness, shyness, lack of confidence. But I don’t rule out other explanations. I’m always looking for ways to open them up, always considering how my own classroom behaviors may be encouraging or stifling their willingness to speak out, but I have to admit that I allow little if any space in my lesson plan for the reactions mentioned above. Ray’s research informs her that “emotions are central to student success,” but in my classroom students are mostly left to deal with their feelings on their own.

In his 1992 book, Ecological Literacy, David Orr discusses the tasks of the liberal arts. Among them, he says, is “to provide a sober view of the world, but without inducing despair.” Since I began to teach in the humanities, Orr’s quote has been a kind of guiding star from me. Ray’s talk has made me revisit it.

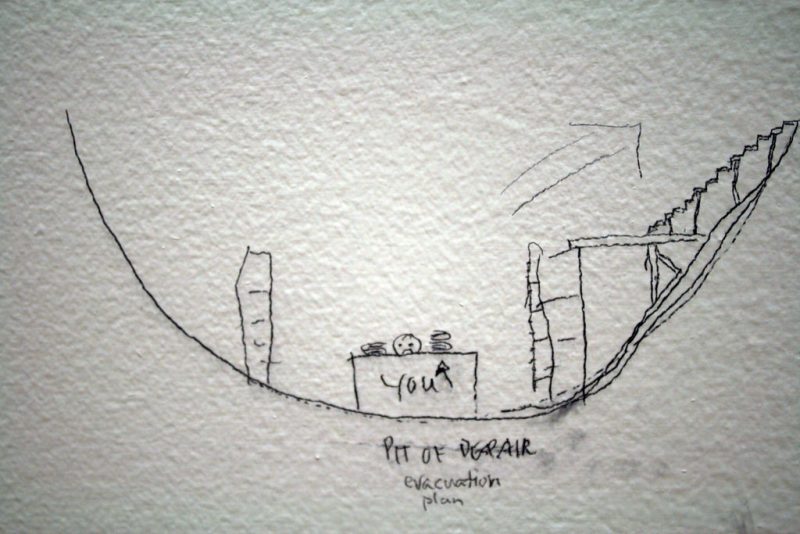

Pit of Despair Evacuation Plan. Image by Quinn Dombrowski of Berkeley, USA

For one thing, I can see how I do plenty for the soberness. History is not an uplifting topic, American or otherwise. Brutal exploitation seems to be the default setting for humankind. An arc of justice is barely discernable, if one even exists. Sometimes my students will admit that they find history a downer. Their response is a typical mix of fatalism and cynicism. “History always repeats itself.” “People treat other people like crap.” These are intelligent responses. They are intelligent responses in a society—indeed, a worldview–built on the underlying message: “Get yours while you can.” I want students to think past these responses—I don’t want to simply reinforce them. But do I actually do anything to try and achieve that outcome? What do I do explicitly not to induce despair?

This isn’t the same thing as giving students hope, though it’s often put that way. I think Ray would agree. “I’m not really interested in hope,” she said. “I’m interested in affective resilience.” What does that mean? Facing reality, rather than, say, feel-good propaganda, exacts an emotional price. Resilience allows us to pay it from a healthy account. I believe that building academic skills, and especially critical thinking—(which calls for some disinterest!)–builds what Ray calls resilience. I might even say that I’m emotionally invested in that belief. But how upfront am I about that investment?

Here’s another way I’m interrogating Orr’s advice that we provide a sober view of the world without inducing despair. Again, it concerns demographics. If one’s students are white, especially white middle and upper class, I can see how some sobering might be required. Entitlement paints a rosy picture. My students are majority urban Latino and African American. Many if not most know poverty, by proximity if not firsthand. I can’t say for sure, but it’s hard for me to imagine that they don’t already have a sober view of the world. I can’t say for sure because of my own privilege. I’ve struggled economically, but I’ve never felt the threat of poverty so as to narrow my most important decisions to the strictly economic. If I can’t relate to my students’ points of view—racially, economically, culturally, or simply because I’m a good deal older than they are—how can I tell how sober their view of the world really is? Maybe this too could be aided by more transparency in regard to the emotional content. A line from Ray’s talk seems relevant here: “Centering emotions is a matter of educational equity and inclusion.”

The last part of Ray’s quote that I wrote out in full above refers to “cultivating resistance.” Resistance and resilience are similar-sounding words, and reading through Ray’s talk, I kept hearing one in place of the other. But they aren’t the same thing. Resilience—affective resilience was the term—is the capacity to effectively process despair, which in turn makes resistance possible. Resistance, in this sense, is political. It’s action and that action is collective. Another piece of Ray’s application was to offer students teaching in the history of social change and to teach them social change theory. There’s a lot more in her advice, in other words, for a teacher of history to chew on.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I am not in the classroom but spent a good chunk of my life in one. It seems to me that a good question to ask is, how could things have gone differently? Using the imagination about alternative possible worlds can help people think about what might be possible now. History is not a given fate, we make it (Good time to read Bellamy or Gilman). Therefore, we can choose something else in the future. This speculative approach might make some historians uncomfortable but I think it would help students not think everything is set in stone which of course leads to fatalism and despair. What if every freed slave had been given 40 acres and a mule? Could the constitution be reconsidered for a new age? If so, how? Just a thought.

Ideas worth thinking about–thank you!

Anthony, this is beautifully written, as ever. Thanks for foregrounding the intangibles of teaching — and that’s a crucial part of it, intangibility. Being emotionally present for one’s students, but also beyond their reach (and vice versa, certainly.)

I have been wondering how or whether my teaching style will reshape itself in some major way as I begin a job at a completely different institution with very different student demographics than those I’ve taught most recently. There are some commonalities: lots of first-generation college students and non-traditional students, maybe more so even than at UT Dallas — perhaps even on a par with a community college in the DFW area. At the same time, very few international students, including almost no Asian students. The percentage of Latino and Black students is about the same as at UTD, while the percentage of white/non-Hispanic students is quite high.

At the same time, something like 63% of Tarleton students receive need-based aid compared to 50% of UTD students (this per US News), and the average starting salary for graduates of Tarleton is about $10,000 lower than UTD graduates. And, unlike UTD, where the student body skews male, the student body ratio among Tarleton undergrads is 55% women to 45% men. So this is a less advantaged student body — less economically advantaged, more conservative, more regional, more rural.

So in a way I feel like I already know these students going to this rural college in the middle of cattle country, in the middle of farmland — it reminds me of where I grew up, and who I grew up with, and who I was, and who my friends were and what seemed possible to us.

But I won’t really know them until we can take each other’s measure. I’m very interested — and not a little anxious — to figure out how I will come across as a prof in this new place, and what my students will need from my teaching that I will have to learn or re-learn how to offer.

Thanks so much for taking the time and finding the words to identify this crucial work of the professor, a work that takes place in a register that’s often not even legible. How do you convey moral courage? How do you speak the truth boldly and handle hearts gently at the same time? And if you just wave your hand and say it’s not a professor’s job to have any truck with hearts, we’re only working with minds, and we can’t worry about whatever lies beyond pure intellection — well, you’re gonna be awfully confused about this job, and will probably do some damage to hearts and minds both.

“Handle with care” — that’s the implicit label on every class roster. I think as long as we’re careful — as you are careful here, even careful to acknowledge how in the dark you may be about who your students are and what they need — we are on the right track.

Hope so anyhow.

Anthony – Thanks for the nice essay. You’d probably appreciate an article I read this morning by Nathaniel Rich, “Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change,” NYT 8.1.18.

Appreciate the Rich link, Bill. On my queue.

FYI, at The Intercept, Naomi Klein writes about “the unfathomably large blind spot” in Rich’s NYT Magazine’s piece: https://theintercept.com/2018/08/03/climate-change-new-york-times-magazine/