Editor's Note

This is the fifth in a series of guest posts by Rebecca Brenner, a doctoral candidate (ABD) in early American history at American University in Washington, DC. She has served as Secretary of the Society for US Intellectual History since June 2017.

by Rebecca Brenner

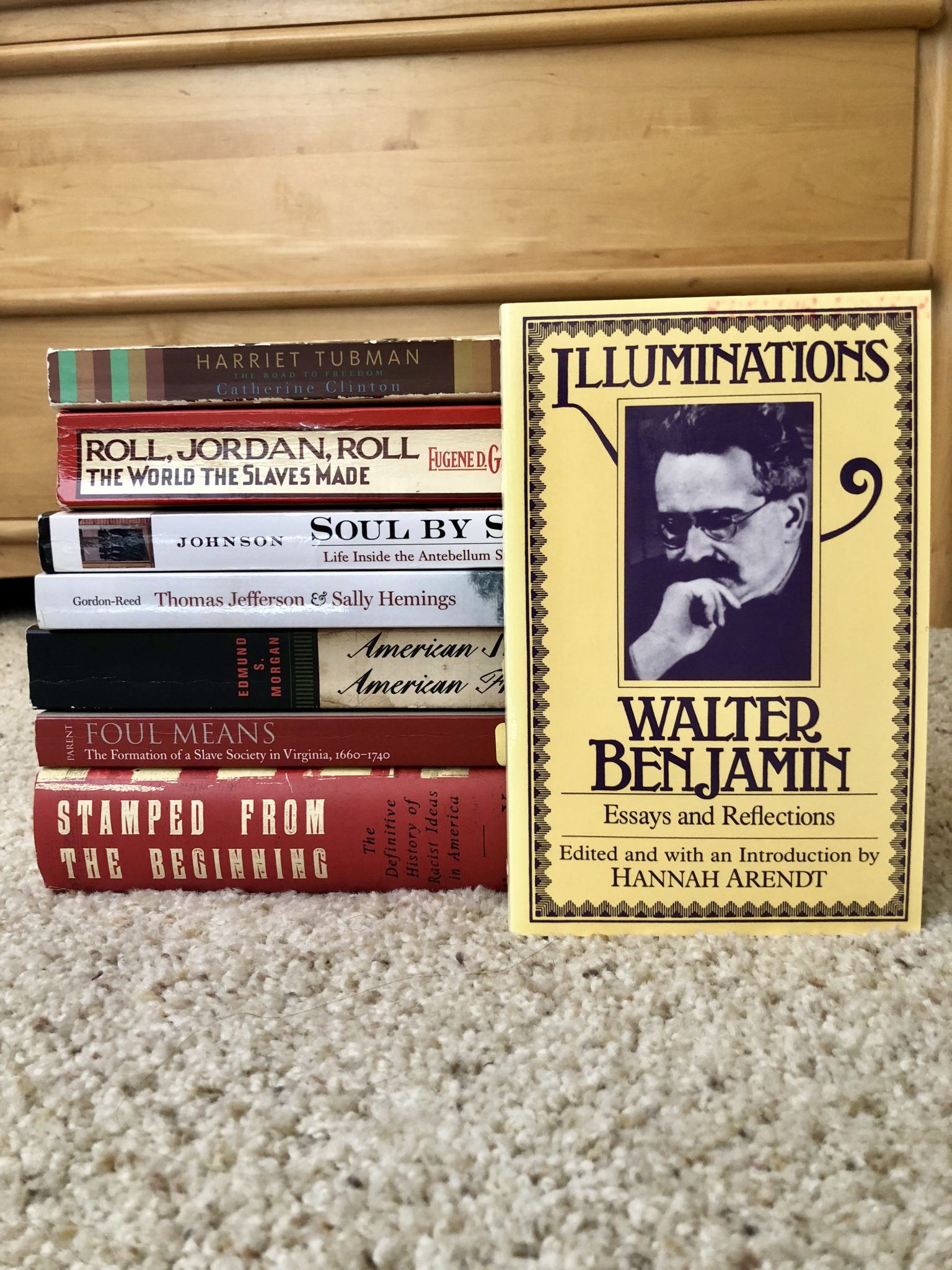

Social theorist Walter Benjamin famously urged historians to write “against the grain.” He meant that marginalized populations left few evidentiary trails and that it becomes historians’ responsibility to work around this limitation. Recently, scholars of early African American history have written “against the grain” in the Benjamin sense. I argue first that early African American historiography witnessed the rise and fall of what Walter Johnson dubbed the “agency trope.”[1]And second, moving beyond the agency trope demanded shifts from trusting slaveholders’ records, to reading slaveholders’ records “against the grain,” and ultimately analyzing non-slaveholder sources about slavery “against the grain.”

In context, “historical materialists” are the ones brushing “against the grain.”[2]Benjamin writes: “Historical materialism wishes to retain that image of the past which unexpectedly appears to man singled out by history at a moment of danger.”[3]Essentially, historical materialists apply history to improve desperate situations. Then: “Whoever has emerged victorious participates to this day in the triumphal procession in which the present rulers step over those who are lying prostrate. According to traditional practice, the spoils are carried along in the procession. They are called cultural treasures, and a historical materialist views them with cautious detachment.”[4]Applying Benjamin’s words to the historiography of enslaved African Americans, “cultural treasures” are the official records that survived. Historical materialists are the historians studying a world in which most of the participants could not leave records. However, writing history “against the grain” means not only pursuing unobvious sources, but also applying history to alleviate danger. This last point applies to recent historians who replaced the agency trope.

Eugene B. Phillips’s 1918 American Negro Slaveryand Stanley Elkins’s 1959 Slavery each dehumanize enslaved persons by relying on slaveholders’ writings, which instead should require “cautious detachment.” Phillips claims that slaveholders treated enslaved persons well and that slavery was only economically inefficient. Through slaveholders’ records, he attempts to argue that slave-owners provided for the people who lived and worked on their plantations. Needless to say, the “cultural treasures” that proponents of slavery left behind reveal a limited perspective. Then in 1959, Elkins argued that slavery infantilized people, rendering them helpless. Phillips’s claim of slavery’s mere economic inefficiency and Elkins’s pseudo-psychological diagnosis of infantilization both dehumanize men and women who were enslaved.[5]

Eugene B. Phillips’s 1918 American Negro Slaveryand Stanley Elkins’s 1959 Slavery each dehumanize enslaved persons by relying on slaveholders’ writings, which instead should require “cautious detachment.” Phillips claims that slaveholders treated enslaved persons well and that slavery was only economically inefficient. Through slaveholders’ records, he attempts to argue that slave-owners provided for the people who lived and worked on their plantations. Needless to say, the “cultural treasures” that proponents of slavery left behind reveal a limited perspective. Then in 1959, Elkins argued that slavery infantilized people, rendering them helpless. Phillips’s claim of slavery’s mere economic inefficiency and Elkins’s pseudo-psychological diagnosis of infantilization both dehumanize men and women who were enslaved.[5]

Edmund S. Morgan and Anthony S. Parent explore slavery’s origins. Morgan’s 1975 American Slavery, American Freedom relays how “slavery and freedom… grew together.”[6]He uses colonial Virginia as a window into the paradox that freedom and slavery enable each other. Bacon’s Rebellion marked the point where whites used racism to divide poor whites from enslaved African Americans. Parent’s 2003 Foul Means builds on Morgan by considering the “role of slavery in Virginia’s social formation from 1660 to 1740, when the Old Dominion assumed its distinctive character.”[7]Parent writes: “Foul are the means of making slavery… Foul is the rationale for the ‘casual killing of recalcitrant blacks: that murderous violence was necessary to check their obstinacy and the legal fiction that such murder was not felony homicide because slaveholders’ self-interest in property precluded a propensity for malice.”[8]Reading Parent and Morgan together, foul were the means of American freedom. They explain how and why white Virginians started treating African Americans as if they were subhuman. While they each used traditional sources, Morgan and Parent slowly begin to push against the grain.

Eugene Genovese’s 1972 Roll, Jordan, Roll and Walter Johnson’s 1999 Soul by Soulare emblematic of the agency trope. Historical agency refers to an ability to influence the course of events. Roll, Jordan, rolltraces daily life on a plantation, highlighting the limited acts of resistance. In Soul by Soul, Johnson moves the discourse away from plantations by focusing on the slave trade itself in New Orleans. Johnson analyzes what he interprets as the central paradox of the antebellum south: slave-buyers attempted to dehumanize other humans. He compares late-nineteenth century narratives of former slaves to early-nineteenth century slaveholders’ records. Each chapter leads to the actual sale, which Johnson uses as a window into the system itself. Like Genovese, Johnson emphasizes individual acts of resistance.[9]

Just four years after publishing Soul by Soul, Johnson pivots and takes the field of African American historiography with him. His 2003 “On Agency” contends that restoring the agency of enslaved men and women is inadequate at best and harmful at worst because many historians congratulate themselves for not being racists, while people of color endure slavery’s legacy. Self-congratulatory behavior defies Walter Benjamin’s warning to treat “cultural treasurers” with “cautious detachment” because the historical institution of slavery continues to benefit white people. Johnson departs from his own work and from the scholars who influenced him by unpacking the “canonical” agency trope, stating that enslaved people were obviously human and therefore did what humans do: resist.[10]Furthermore, the agency trope “reduces acts of resistance to manifestations of a larger, abstract human capacity,” thereby overlooking the tangible consequences.[11]

“On Agency” especially critiques Roll, Jordan, Roll and Johnson’s own Soul by Soul. For Johnson, the limits of Genovese’s Marxist definition of revolution cause Genovese to claim that enslaved men and women lacked revolutionary aspiration. Additionally, Genovese writes that they were unwilling to revolt due to plantation culture. And finally, Johnson critiques Genovese’s separation of collective from individual resistance.[12]But perhaps he reserves the strongest critique for his own work: “If we are to draw credibility by doing our work in the name of the enslaved and then seek to discharge our debt to their history by simply ‘giving them back their agency’ as paid in the coin of a better history… I think that we must admit we are practicing therapy rather than politics: we are using our work to make ourselves feel better and more righteous.”[13]Johnson admits that his emphasis on African American humanity in Soul by Soulwas selfish. He resolves to focus on broader systems with consequences today. “On Agency” writes against the grain by vowing cautious detachment toward the self-congratulatory agency trope.

Historians such as Catherine Clinton and Thavolia Glymph have transcended the agency trope by bringing African American women into the narrative through innovative methods. In Harriet Tubman, Clinton presents Harriet Tubman not only as a mythical figure, but also as a courageous human being. Clinton’s biography of Tubman resembles the restoration of humanity narrative, but she uses circumstantial evidence to spotlight an extraordinary woman in African American history.[14]In Out of the House of Bondage in 2008, Thavolia Glymph analyzes white women’s role in oppressing Black women. Notably, Glymph’s analysis of Works Progress Administration slave narratives’ biases enables their use as sources.[15]Clinton relays Tubman’s exceptional story, and Glymph exposes white women’s agency in perpetuating slavery, which are both more nuanced than the agency trope.

Annette Gordon-Reed’s scholarship reads history against the grain through the use of circumstantial evidence and by taking seriously the perspectives of men and women who were enslaved. Gordon-Reed’s 1997 Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemingsdoes not claim that Jefferson definitely fathered children with Hemings, but instead crafts a convincing argument that this was indeed the case. She applies her legal training to use circumstantial evidence and logic, concluding that previous historians’ racism hid the truth. Building on her first book, Gordon-Reed’s 2008The Hemingses of Monticello points out that exclusively telling founders’ stories negates the stories of the Hemingses and other Black perspectives. Most recently in 2016, Gordon-Reed and Peter Onuf’s “Most Blessed of the Patriarchs”: Thomas Jefferson and the Empire of the Imagination chronicles Jefferson’s self-perception, while integrating the Hemings story.[16]Gordon-Reed’s scholarship retains the spirit of the “historical materialist” in Benjamin’s Theses VI and VII.

“On Agency” argues for analyzing “structures of exploitation,” which River of Dark Dreams

and The Internal Enemy both achieve.[17]In 2013, Johnson’s own River of Dark Dreams analyzes the institution of slavery to illuminate its place in the global economy. Johnson traces records of property to reveal the daily realities that enslaved people faced when slaveholders treated them as property. He draws on charts, graphs, other financial records, and other sources, all tying slavery closely to the rise of global capitalism. Connecting slavery with American capitalism implicates the north, too, suggesting widespread complicity in the institution.[18]In these ways, River of Dark Dreams epitomizes both innovative sources and moving beyond the agency trope. Also, in 2013, The Internal Enemy by Alan Taylor argues that enslaved people sought freedom, slaveholders subdued them, and British troops exploited this tension during both the American Revolution and the War of 1812. Enslaved men and women tried both successfully and unsuccessfully to seize freedom when outside parties, mainly the British, presented opportunities. The letters and other materials of refugees in Nova Scotia from slavery comprise the bulk of Taylor’s research.[19]Both 2013 monographs focus on broad structures, each hastening agency trope’s downfall by reading and writing against the grain.

Most recently, Stamped from the Beginning by Ibram Kendi rereads an enormous quantity of primary sources against the grain to create a new interpretation. Kendi writes: “Self-interest leads to racist policies, which lead to racist ideas leading to all the ignorance and hate. Racist policies were created out of self-interest. And so, they have usually been voluntarily rolled back out of self-interest.”[20]He introduces a new vocabulary for distinguishing among “racist,”” assimilationist,” and “anti-racist” ideas, and all people serve as carriers of these ideas.[21]For the early republic, Kendi focuses on racist Thomas Jefferson and assimilationist William Lloyd Garrison as “tour guides.”[22]While “On Agency” claims that many people are too proud of supposedly not being racists, Kendi demonstrates that all people are capable of carrying racist, assimilationist, and anti-racist ideas, and self-interest largely determines which ideas people carry.[23]Stamped from the Beginning epitomizes the engagement with contemporary issues that Walter Johnson’s “On Agency” and Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History both demand.[24]

“Against the grain” means innovating new sources or reading old sources innovatively, as well as moving beyond the agency trope, in the context of early African American historiography. The “cultural treasures” from the “triumphal procession” refer to how Philips and Elkins each used sources from the people who oppressed others to illuminate only the perspectives of those with power. Morgan, Johnson, Gordon-Reed, Clinton, Glymph, Taylor, and Kendi, among others, have written history “against the grain,” with rising intensity at each historiographical milestone.

__________________

[1]Walter Johnson, “On Agency,” Journal of Social History(Fall 2003)

[2]Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History, Thesis VII, http://pages.ucsd.edu/~rfrank/class_web/ES-200A/Week%202/benjamin_ps.pdf.

[3]Benjamin, Thesis VI.

[4]Benjamin, Thesis VII.

[5]Ulrich B. Philips, American Negro Slavery(1918); Stanley Elkins, Slavery(1959); Stanley Elkins, Slavery (The University of Chicago Press, 1959)

[6]Edmund S. Morgan,American Slavery, American Freedom (New York: W W Norton & Co, 1975) 6.

[7]Anthony S. Parent, Foul Means: The Formation of a Slave Society in Virginia, 1660-1740 (University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

[8]Parent, 266

[9]Eugene D. Genovese,Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York: Vintage Books, 1972); Walter Johnson, Soul By Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Harvard University Press, 1999).

[10]Walter Johnson, “On Agency,” 115, http://www.havenscenter.org/files/OnAgency.pdf.

[11]Johnson, “On Agency,” 117

[12]Johnson, “On Agency,” 117

[13]Johnson, “On Agency,” 121

[14]Catherine Clinton, Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom (New York: Little & Brown, 2003).

[15]Thavolia Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

[16]Annette Gordon-Reed, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy (University of Virginia Press, 1997); Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008); Annette Gordon-Reed and Peter Onuf, “Most Blessed of the Patriarchs”: Thomas Jefferson and the Empire of Imagination (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2016).

[17]Johnson, “On Agency,” 121

[18]Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (Harvard University Press, 2013).

[19]Alan Taylor, The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013).

[20]Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (New York: Nation Books, 2016) 506.

[21]Kendi, 2-4.

[22]Kendi, 8.

[23]Johnson, “On Agency,” 120

[24]Johnson, “On Agency,” 121

0