Editor's Note

This is one in a series of posts examining The American Intellectual Tradition, 7th edition, a primary source anthology edited by David A. Hollinger and Charles Capper. You can find all posts in this series via this keyword/tag: Hollinger and Capper.

This post examines some of the texts included in Volume II, Part Two: Social Progress and the Power of Intellect. Here are all the texts included in this section:

Jane Addams, “The Subjective Necessity of Social Settlements” (1892)

Thorstein Veblen, selection from The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899)

Woodrow Wilson, “The Ideals of America” (1902)

W.E.B. Du Bois, selection from The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

William James, “What Pragmatism Means” (1907)

Walter Lippmann, selection from Drift and Mastery (1914)

Madison Grant, selection from The Passing of the Great Race (1916)

Randolph Bourne, “Trans-National America” (1916); “Twilight of Idols” (1917)

H.L. Mencken, “Puritanism as a Literary Force” (1917)

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., “Natural Law” (1918)

John Dewey, “Philosophy and Democracy” (1918)

Joseph Wood Krutch, selection from The Modern Temper (1929)

John Crowe Ransom, “Reconstructed but Unregenerate” (1930)

Ruth Benedict, selection from Patterns of Culture (1930)

Sidney Hook, “Communism without Dogmas” (1934)

Now we are in the heart of the batting order. This section of Hollinger and Capper’s second volume features not just important ideas and important debates, but names we recognize as important thinkers – nay, professional thinkers. This section of Hollinger and Capper gives us a straight dose of that character we have long debated and discussed at this blog: the public intellectual.

Yes, some of our authors were ensconced in – or at least salaried by – academe (on the other hand, Veblen was defiantly unensconceable), but they addressed and attracted broader audiences for their ideas, and the arguments they distilled in their implicit and explicit challenges to one another’s positions on the issues of the day reverberated in other arenas of American life. If I wanted to convince a dubious student of the value of the study of “social thought,” more particularly “American social thought,” this is the period I’d start with, and this is the section where I’d begin, my fondness for the dynamic whirl of modernity’s multiplicitous advent notwithstanding.

The thingness of “American social thought” – that it is or can be an object of inquiry, that there is a there there to be discussed and explored and understood – is self-evident to American intellectual historians or historians of American thought and culture. And at this point even non-specialists can recognize the thingness of “American social thought,” for it is a course catalog listing at many a college and university. American social thought has a slot in the curriculum, and even in small departments where the course is not offered every year, it is there, holding space, taking up a number that might at any moment be drafted into service, depending on the needs of the department or the school or the university.

But in what does the thingness of American social thought consist? Why does it seem so tangible, so consequential, when we come to these particular scholars and their polemics and debates and prescriptions and proscriptions?

The tempting answer to this question is that we can clearly see among these thinkers that social thought had high-stakes social consequences that they themselves had a hand in bringing about – or, to subvert any “great thinker” theory of intellectual history, we can see that these thinkers most clearly channeled or reflected the sensibilities of the era that we can also read in contemporary events. Jane Addams’s ideas about the value of settlement houses articulated and/or spurred an entire movement among middle class women and men. Her theory became widespread practice. Dewey’s educational theories became widespread practice. In an age of empiricism, Jamesian experimental pragmatism was not simply the interesting notion of one sensitive, sensible, and beautifully unsystematic philosopher – it was the modus operandi for his countrymen and his country.

This section, perhaps more than any other so far, features “eventful” writings – we can match these ideas up to the “one damn thing after another” of American history in their moment.

But – or and? – what distinguishes this period and these thinkers is not so much that their ideas had “social consequences” or reflected “broader social currents.” It’s that “the social” was immanent in their thinking. That is, their conception of American life, their notions of the political order as it was or as it should be, their gauge of what was or was not desirable or possible or respectable or worthy of sacrifice or dissent – all of these values found expression in decidedly collective terms. Though we can see the influence of Emerson on James, the Emersonian individual, the Thoreauvian lone protestor – and, for that matter, the Edwardsian single soul dangling on a spider-thread over the fires of eternal damnation – are all but forgotten. (Randolph Bourne takes the baton from Thoreau, but in some ways that sense of some lone courageous voice of dissent dies with him.)

What sets these thinkers apart as belonging to an age of their own is the one-another-ness of their conception of American life. But, you say, one-another-ness is not a new idea in American thought. Indeed, the Hollinger and Capper volumes begin with one of the most famous articulations of one-another-ness – interdependence, being in it together, being not an agglomeration of individuals but a complete society in which each part needs and is needed by the whole – in the Arbella sermon of John Winthrop. But in John Winthrop’s conception of the social order, that human interdependence is meaningful only insofar as it is an expression of the will of God and an undertaking for the glory of God.

What sets these thinkers apart as belonging to an age of their own is the one-another-ness of their conception of American life. But, you say, one-another-ness is not a new idea in American thought. Indeed, the Hollinger and Capper volumes begin with one of the most famous articulations of one-another-ness – interdependence, being in it together, being not an agglomeration of individuals but a complete society in which each part needs and is needed by the whole – in the Arbella sermon of John Winthrop. But in John Winthrop’s conception of the social order, that human interdependence is meaningful only insofar as it is an expression of the will of God and an undertaking for the glory of God.

By contrast, in these readings from the Progressive Era – for that’s the “event frame” to which this section of Hollinger and Capper respond – God does not seem to be anyone’s particular concern, except insofar as concepts of God might get in the way of justice and goodness in the here and now. (There is an exception, of course: this is precisely the sensibility that John Crowe Ransom attacks in “Reconstructed but Unregenerate.” However, Ransom’s dissent only serves to highlight the dominant intellectual current of the era.)

So it would be easy to read this section as evidence of the “secularization” of American life and thought.

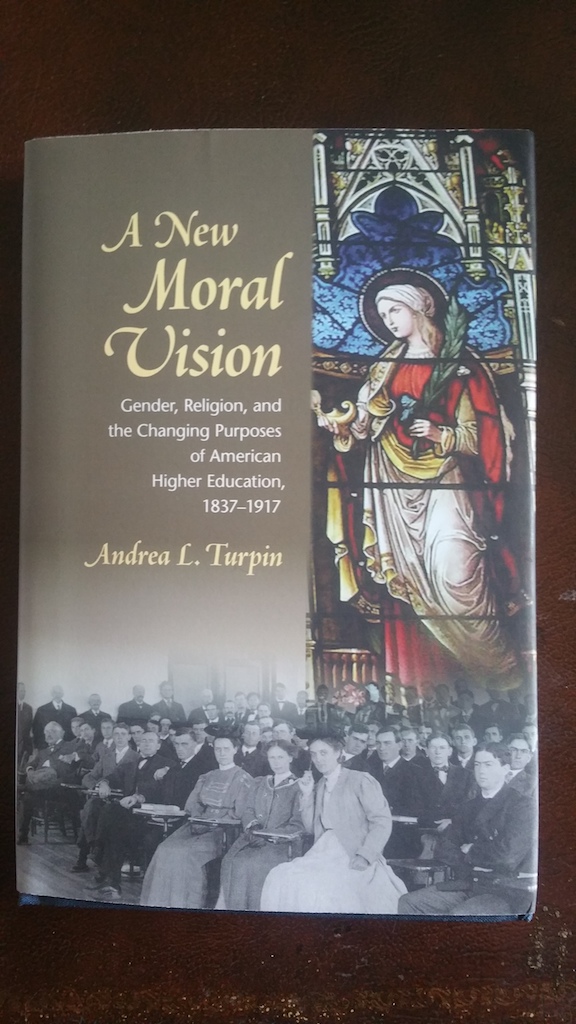

In her award-winning book, A New Moral Vision: Gender, Religion, and the Changing Purposes of American Higher Education, 1837-1917, Andrea L. Turpin suggests that the familiar idea of “secularization” can obscure as much as it clarifies (my words; not hers).* At least as far as we consider changes within American Protestantism or American Protestant culture broadly construed, Turpin argues that there was not so much a shift from the sacred to the secular as an axial reorientation of (broadly) Christian thought and belief from a concern with transcendence to a focus on immanence.

Evangelicalism and [Christian] modernism assumed that both people’s relationship with God and their relationships with fellow humans were broken and in need of repair, and they each incorporated spiritual approaches oriented toward restoring relationships on both planes. However, evangelicals emphasized vertical, God-oriented spirituality and modernists emphasized horizontal, interpersonal-oriented spirituality. Evangelicalism considered the break in the human-divine relationship the primary one: fix that and harmony on the interpersonal plane would follow because each person would have a new heart that wanted to obey God’s laws. Hence, what was needed first was repentance and faith in Christ, which was to say “conversion” or a “decision for Christ.” This conviction explains why evangelicals placed a greater emphasis on doctrine: relating rightly to an unseen being required thinking rightly about the nature of God. Modernism, meanwhile, considered the interpersonal break the primary one: the problem in people’s relationship with God was that they had not obeyed divine commands about how to treat one another; fix that and the relationship with God would also be repaired. Hence, what was needed first was a new commitment to following Christ’s teachings, often referred to as “a decision for the Christian life.” This conviction is why modernists placed a greater emphasis on spelling out interpersonal ethics: getting that part of spirituality right was the real key to a righteous life in all respects. Thus modernists often constituted the prominent leadership of the “social gospel” movement dedicatd to restructuring society along Christian principles, although some evangelicals also embraced the movement as an outworking of their faith in Christ, and many modernists interpreted interpersonal ethics in a more individualistic way (17-18).

This is a really intriguing and useful way of framing the shift to “the social” in expliciltly religious American thought, but also in American thought most broadly construed, especially when we consider American society as sort of generically Protestant.** Indeed, David Hollinger’s work argues that American society is much less generically Christian than we might think – that liberal modern mainstream Protestantism so infused the whole culture with its values and beliefs that the dissolution of that Christian movement’s formal institutional influence in American life is not a vanishing act, but a sign of full incorporation. A little leaven leaveneth the whole lump.

Now, H.L. Mencken might caterwaul at the thought of being part of a broad “leavening” of American life and culture with the values of a one-another-ness that sought to make sure that all’s right with God and man (Mencken and Veblen are in some ways two peas in a pod in this respect, though Mencken was more of a sour little spore), but his iconoclastic skepticism was the counterpart to Ransom’s traditionalist fideism – both were railing in common against the current of their era, and neither wished to be swept along with any commoners or anything common.

But let’s float along in that direction for just a bit. Let’s think about what the emphasis on one-another-ness and the de-emphasis on God-and-man-ness in American social thought implies. Let’s think about what it implies for historians of American social thought, since we’re still carried by the currents swirling around Mencken and Addams and Ransom and James.

How has a sense of one-another-ness shaped our professional lives and our place in society? Have we been sensible to that ethos? Have we embraced it? Have we resisted it? Have we instantiated it? Have we betrayed it?

I have often thought that the secular academy as an institution is like the church in all respects save one: we have every flaw and every virtue of the church to offer to the world, except for grace. That we cannot give. That is not our table.

I do not offer that observation in judgment, or as a suggestion that the secular academy needs to become “more like the church” (no thank you!), or that we are somehow failing in our work if we are not ministers of grace to one another or the world. Don’t misunderstand me.

But do understand me: I think the academy would do well to reflect on the importance of foregounding our (secular but no less valuable) one-another-ness, a sense of being “knit together” as a whole, not for the glory of God, who may or may not exist to us nor we to God, but for goodness’s sake. For goodness sakes! For each other’s sake and our own. For the world’s sake, if academe has any relevance in the wider world or any role to play in its much-needed improvement.

Here the corporal metaphors of Paul, from which John Winthrop borrowed his joints and sinews of affection, are relevant. (Then again, I think academe is institutionally the shadow-twin of the church.) You are one body with many members…When one member suffers, all the members suffer. When one member is honored, all the members rejoice together. I think we would do well to keep that in mind. For academe can be a very hell of egos, and there is no ego more hellish to be trapped in than one’s own. Much better, much more peaceful, to be here for one another, present to one another.

Think of the #MeToo movement in academe, and why it’s happening, and why it’s needed. An academic who harasses or bullies someone among us is not just hurting that person, nor is such an academic just hurting their own reputation (or “protecting” or burnishing their own reputation with their bullying); they are hurting all of us, they are implicating all of us, they are damaging the one-another-ness that we must hold on to if we are to do any good or know

any good through our work.

Because there is nothing else for the secular academy — or the secular age — but one-another-ness. There’s no one else’s grace on offer. It is all on you and me, and we are all we’ve got.

No heaven – or hell – in the here and now but who we are as and to one another.

__________________

*Side note: I would like to know what person or persons, what era’s famous text or famous debaters are responsible for injecting into our discourse this frequently used shorthand: “obscures more than it clarifies.” This is a common polite rejoinder in historiography, a verbal cue that we’re about to say that someone’s explanation misses the boat because it fails to account for, or doesn’t recognize, or conflates x, y, or z. It’s a verbal tic of historians, and I am interested, for mere curiosity’s sake, to know where we picked it up. There’s a whole history beneath that intellectual shorthand.

**Speaking of “the social” and the Social Gospel, I would suggest losing one of Randolph Bourne’s readings (or booting Joseph Wood Krutch) and using something by Walter Rauschenbusch.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this. The Progressive Era, as it is commonly known to us historians, has long been my favorite period to teach. It’s about the clash and confusion of ideas. I love discussing the advent of American modernity—and its unique thinkers, confusion about religion, and implications for literature, criticism, and culture overall. I appreciate you forwarding Turpin’s framing. It resonates. To me, all of this comes together in teaching the Twenties. If that decade “roars” for me, its an intellectual roar. – TL

Amazing post! Many thoughts and ideas in here. Thanks especially for the reminder to read A New Moral Vision, which I bought and expect to love. Fascinated by your explanation of Jane Addams as an intellectual not only through her academic sociology, but also through her social role. I think the same of Rebecca Gratz, who single-handedly transformed what it meant to be a Jewish American woman socially and spiritually in early American Philadelphia. In fact, the religious-to-secular — now disproven many times — obscured religious minority narratives in the U.S. Anyway, thanks again for a thought-provoking post and the reminder to read A New Moral Vision!

Thanks Tim and Rebecca —

Yes, this era roars — though for me it’s not just the ’20s, but the whole GA/PE. It’s as if the times begin to turn on a hand-crank, like one of Edison’s phonographs, or like a record on a Victrola gaining speed until the sound comes through clear — “He hears his master’s voice.” And how rapidly the whole era must have been turning, that we can still hear the sound of it now.

On Turpin’s book, I will have a post, elsewhere/when, about some crucial historiographic lessons and some crucial writing lessons I am picking up from this book. There are certainly multiple reasons that it was an award-winner, and now is a good time for me to read it. I’m (very busy NOT) writing a chapter that I thought I would love, but actually hate — because #MeToo, because harassment and bullying in academe, because, because, because. But it has been helpful and refreshing to follow along with Andrea Turpin. If she hate-wrote any part of this book, it doesn’t show. And there are lessons there too.

Anyway, thanks for reading and commenting.