Editor's Note

This is one in a series of posts examining The American Intellectual Tradition, 7th edition, a primary source anthology edited by David A. Hollinger and Charles Capper. You can find all posts in this series via this keyword/tag: Hollinger and Capper.

This post examines some of the texts included in Volume I, Part Five: The Quest for Union and Renewal. Here are all the texts included in this section:

John C. Calhoun, selection from A Disquisition on Government (c. late 1840s)

Louisa McCord, “Enfranchisement of Woman” (1852)

George Fitzhugh, selection from Sociology of the South (1854)

Martin Delany, selection from The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852)

Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” (1852)

Abraham Lincoln, “Speech at Peoria, Illinois” (1854); “Address Before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society” (1859); “Address Delivered at the Dedication of the Cemetery at Gettysburg” (1863); “Second Inaugural Address” (1865)

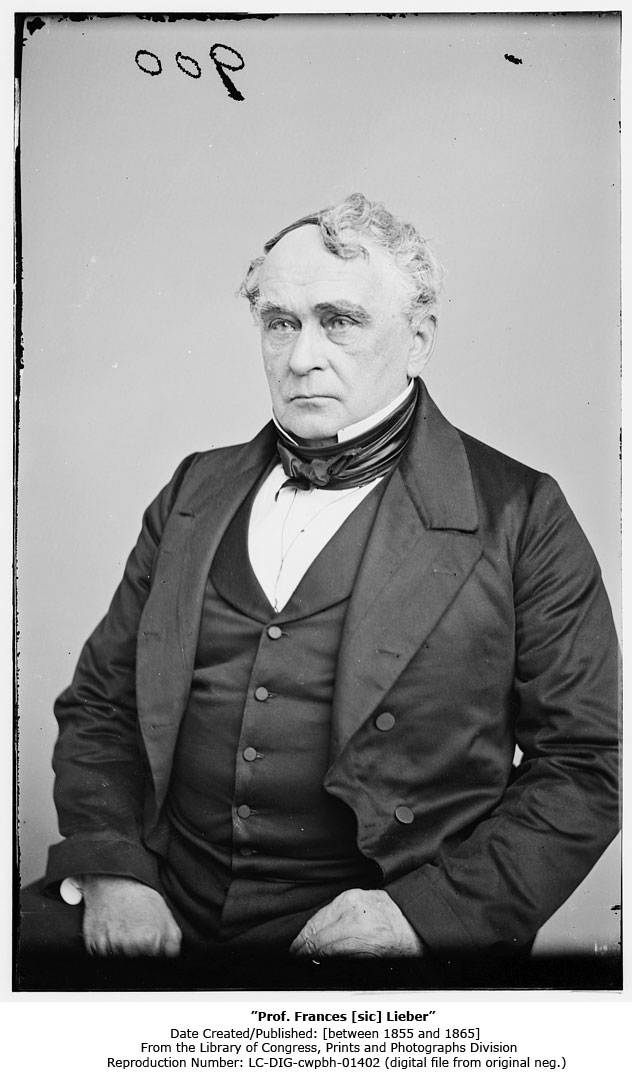

Francis Lieber, “Nationalism and Internationalism” (1868)

A new voice the chorus of American thinkers in this last section of the seventh edition of Hollinger and Capper: Francis Lieber. In this post I’ll say a little bit more about this author and why he is of particular relevance for my own work at the moment – and maybe for yours.

Lieber was a Prussian radical who emigrated to the U.S. in the 1820s, before the ’48-ers, but very much part of the broader community of German immigrants who embraced liberal democracy and free-soil Republican politics. Some of these ’48ers – most notably, perhaps, Carl Schurz – split with the Republican party during the election of ’72 and ran their own “Liberal Republican” candidate, Horace Greeley, for President against U.S. Grant.

Lieber’s presence in Hollinger and Capper introduces another strand in the history of American thought by highlighting the role that immigrants played in shaping ideas of nation and citizenship (including birthright citizenship) during and after the Civil War, and posits a membership of nation-states in a “commonwealth of nations” – a sort of “citizenship” of nation-states in a world community.

I’m reading about the ’48ers now thanks to the interesting overlap between two 19th-century ethnic stereotypes about Germans, represented to some extent by both Lieber and Schurz. The first is the emergence of the idea of the “freedom-loving German,” explored in Alison Clark Efford’s excellent study, German Immigrants, Race, and Citizenship in the Civil War Era (Cambridge, 2013). The second stereotype is that of “the German professor,” a character who loomed large not just in academe but also in popular culture. (Jo March grows up to marry not just a professor, but a Germanprofessor, in the sequel to Little Women.)

Lately, these stereotypes have intersected for me in the person of Schurz, who was not actually a professor, though he was a frequent lyceum lecturer. But Schurz “looked the part” of a professor, and that’s important, because what a professor “ought to” look like has often had a lot to do with who gets to be a professor.

Francis Lieber, on the other hand, wasa professor. He had been a student of Barthold Niebuhr and received his PhD at Jena, and he taught at South Carolina College and Columbia University

I recently came across some of Lieber’s early writing in a different sourcebook: the first volume of American Higher Education: A Documentary History, edited by Hofstadter and Smith. In 1830, Lieber gave an address to a conference of scholars gathered in New York to discuss the state and the future of higher education in America. Hofstadter and Smith reproduce a few pages from Lieber’s speech.

Most interesting to me were two arguments Lieber made about what should be taught in American universities and how professors should be compensated. Lieber argued that there was no need for “a Professor for the history of the United States alone.” Why? You’ll love this: “Every one in this country studies the constitution, and is naturally led to do so.” Sure, Francis. If historians were any good at predicting the future, I think Francis might have changed his mind about the need for specific instruction in U.S. history.

He was adamant about the need for historians, though. And he was equally adamant about how historians and other professors should be compensated. In the 19thcentury (and, apparently, in the 21stcentury), it was common to pay Professors a minimal wage, far less than what they could reasonably live on or support a family on. This was something like their base pay. Their actual pay, though, depended on student fees calculated based on enrollments in their particular classes. A popular professor would be a well-paid professor; a less charismatic or less accommodating professor would suffer pecuniary want.

Lieber believed that making the pay of professors depend upon the judgment of students was a horrible mistake:

A Professor of history might make his lectures popular, nay, he might treat generally parts of history, which are more entertaining than others; but whether he would thus most contribute to the purpose of his appointment is a very different question. The best is not always the most popular. Indeed, I have seen students fill a lecture room for the mere sake of entertainment, because the Professor interspersed his lecture (by no means the best of the university) with entertaining anecdotes. I recollect two such incidents.

Okay. That last sentence is kind of a tell: this isn’t just a general speculation on Lieber’s part. He’s resentful on behalf of some eminence grise (whom he admires) that another eminence grise (whom he does not admire) made his lectures funny enough to draw a crowd. “Shall we go hear the professor who puts us asleep, or shall we listen to the professor who keeps us awake?” One can hardly fault students for choosing the latter. Besides, nothing is more tedious than someone wrapping themselves in aloof inaccessibility as some sort of proof of genius.

Lighten up, Francis.

But Lieber moves from his own particular experiences to a more general observation:

would it not be making students judges of the professors? Competition is excellent, and the vital agent in all things, where the people interested are proper judges of the subject which interests them….But what would be the case in universities established on that principle? youths would judge of men, and in regard to that very matter, which they have still to learn; in which they, therefore, are incompetent, else, they would not need the instruction. I do not deny, indeed, that the intense study found in the German universities is owing in a great measure to the liberty of choice left to students, because liberty produces activity; but I do deny that it would be safe, to let the support of the Professor depend upon the judgment of the students. Have the greater men always been the most popular among the students? By no means….

What’s interesting about this passage, particularly for my work, is how it nicely illustrates the distance between 19thcentury liberalism and 20th

century neo-liberalism. There were still many arenas of life, including education, where “the market” was not considered to be a sufficient arbiter of value. Though individuals were rational actors exercising freedom of choice, the collective knowledge purportedly expressed by “market demand” was insufficient to assign pedagogic worth or educative value. What neo-liberals today call “classical liberalism” is of a rather more recent vintage.

Or is it? Lieber was arguing against a common practice: letting student demand decide the ceiling of professors’ salaries. That practice was mostly set aside as American higher education took its turn toward the modern research university. But we have turned again, back to the contingently employed professoriate, back to the expert in subject matter who must cobble together a living by not alienating either the employer or “the consumer.” So maybe it’s 19th

century liberalism that is the outlier here.

Either way, 19th

century liberalism is where the first volume of Hollinger and Capper ends, and where my argument – and, maybe, everyone else’s – begins.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I recall reading that Kant’s pay, in the early part of his career, depended entirely on how many students attended his lectures (students paid a per-lecture or per-course fee that went to the lecturer). So that was apparently the practice in 18th-cent German univs (for young lecturers before they got a chair of some sort), and elements of it apparently carried on into the 19th cent.

In my (putative) field, Lieber is probably best known for the Lieber Code, a code of conduct for soldiers and armies, e.g. w/r/t prisoners and non-combatants. A cursory search will, I’m sure, turn up a lot of refs and discussions (for anyone interested).

Louis, thanks for your comment. Kant and Saint Augustine both earned their living as lecturers on the same basic scheme. There’s a great passage in Confessions where Augustine talks about students not paying fees. By Kant’s time, there are the rudiments of an institutional interface to regulate / administer fees.

But I really do think that 19th c. liberalism is the exception here, not the norm. The professor as a salaried employee freed from the vagaries of the market is an effect of 19th c. liberalism. (Leslie Butler is good on this re: liberal reformers.)