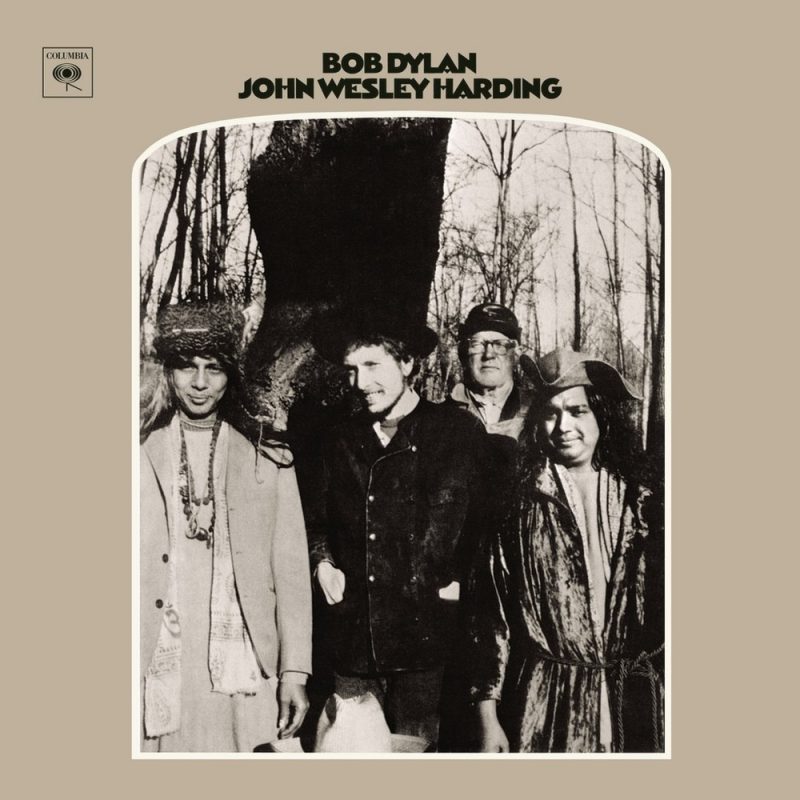

As we mark the fiftieth anniversaries as so many events from a consequential year, let’s include the release of Bob Dylan’s eighth record, John Wesley Harding. Recorded in Nashville in the fall of 1967, it became available to listeners the following January. Along with so many other events, it adds to the perception of 1968 as a turning point year.

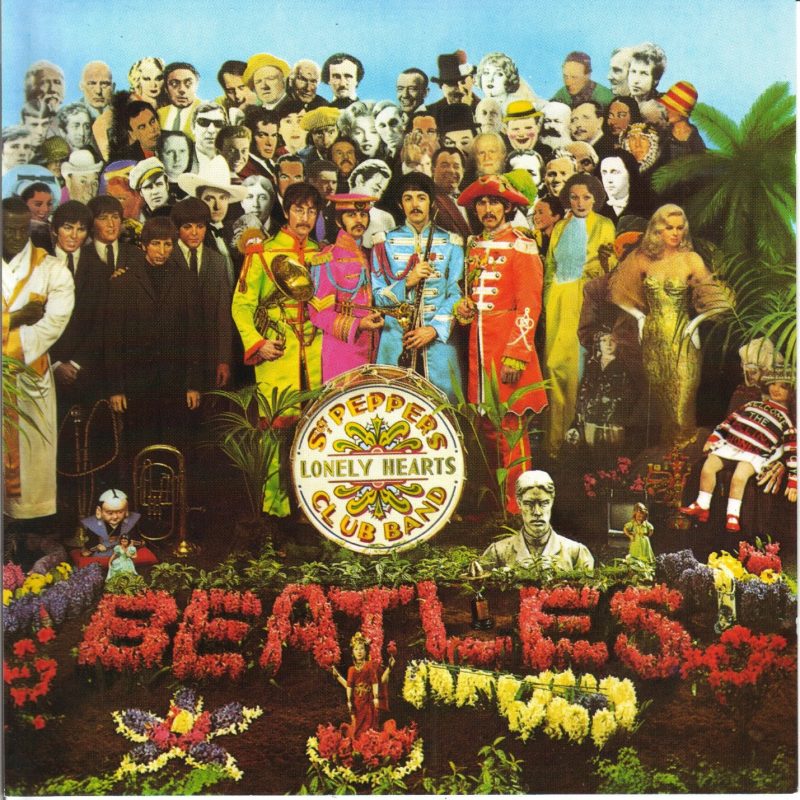

To say that the record was eagerly awaited may be something of an understatement. After breaking from the folk movement and “going electric” in 1965, Dylan had released three ground-breaking records in quick succession. They injected a modernist spirit into popular music, and as an answer to the British Invasion, reclaimed turf lost for the Americans. Dylan’s streak was stopped short, however, by a motorcycle accident, and no new material had been available for a year and half. During that period, The Beatles had released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and pop had entered its psychedelic phase. How would Dylan respond?

This is the way Dylan scholars typically situate John Wesley Harding

This is the way Dylan scholars typically situate John Wesley Harding

, and it makes sense. I was alive and paying attention during the emergence of hip-hop in the 1980s, listening in astonishment to a local radio show that tracked releases week by week. One artist’s single upped the ante on another artist’s previous single, musically, lyrically, and in terms of what this new sound would entail. A genre was being created before our ears–it was a very exciting time. So it’s not hard for me to imagine the excitement surrounding the releases of artists such as Dylan and the Beatles in the sixties and to feel them in real time as commentaries on each other.

Dylan’s answer to Sgt. Pepper

couldn’t have been more contrary. To the Beatles’ embrace of classical motifs and instruments, non-blues tonalities, complex structures, and pastiche, Dylan responded with a subdued collection of songs, Spartan in their instrumentation and arrangements. These were “terse parables,” a disavowal of psychedelia’s “rococo tendencies” and “the season of hype,” as critics have put it. “I was determined to put myself beyond the reach of it all,” Dylan said of the Summer of Love and its trappings, “I … didn’t want to be in that group portrait.” The quote brings to mind Sgt. Pepper‘s elaborate cover art, with its pantheon of historical figures, Dylan included among them.

Dylan: “I … didn’t want to be in that group portrait.”

But the summer of 1967 wasn’t only the Summer of Love. It was the summer of urban racial unrest, the Summer of Vietnam, and Dylan’s record wasn’t a reaction to Sgt. Pepper alone but also to the political radicalism of the period. Two questions were on the table, one might say–the first concerning psychedelia as an aesthetic choice and the second concerning militant activism as a political one. With John Wesley Harding

, Dylan seemed to turn away from both choices.

This was something of a repeat for Dylan. At the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, he’d “betrayed” the folk movement from which he’d emerged by playing with an electric blues band. He was “Judas,” as at least one audience member called out during the tours that followed, because he’d turned away from serious social matters and sold out to commercialism, to pop. The move was defensible as a statement of artistic freedom. Dylan didn’t want his message pre-ordained; he didn’t want his topics restricted to “protest”; he wanted to express himself freely. It was during this period that Dylan rose to fame as a kind of bad boy-genius-provocateur, unafraid of being an asshole, in his songs or in his life. The classic cinema verité documentary, Don’t Look Back, captures the beginnings of this manic period.

Since then, however, protest and resistance had only intensified. The reception of the Tet offensive and the reception of John Wesley Harding were chronologically parallel events. Dylan wouldn’t simply stay on the sidelines of the Movement, the new record seemed to say. He would retreat even further from the fight. Yet if this can be understood as a second betrayal of perceived political obligations, it was different from the first. Rather than staking a claim for expansive individual expression, as he had the first time, Dylan seemed to be checking his own aesthetic and all the entitled rock star behaviors that had gone along with it.

Sonically, lyrically, Dylan sounds penitent, chastened. Gone were the rock and roll drums and stinging, electric guitars. Gone were the long, word-packed lines. Dylan had been writing with great metaphorical flexibility. If the lines themselves were sometimes obscure, the songs themselves weren’t. They were about immediate emotional states–love, longing, sorrow, frustration, anger, ridicule, spite. Most of the time, you knew what he was talking about; he was just doing it in an elaborate way. On John Wesley Harding, it wasn’t the lyrics that were obscure; it was the stories they told that were remote and mysterious.

“All Along the Watchtower,” the album’s best known song (ironically, via a psychedelic cover version by Jimi Hendrix), can serve as an example. On one level, like most of the other songs on the record, it’s a story song without a chorus in the ballad tradition. But it’s as if the bulk of verses had been removed and the remaining ones reordered. It stops where it starts; it seems half lost in time. Were these songs from the American Old West or from the Ancient Near East? Their stories seemed just as at home in antiquity as they were in modern times.

John Wesley Harding‘s songs are not confessional in the way many of Dylan’s other songs were or would be, not confessional in the way the singer-songwriter era, soon to come, would be. These songs are confessional in a religious sense. Their protagonists have been tempted; they’ve transgressed. All of them men, they’ve damaged relations–with other men, perhaps with God, but mostly with women. Now they need to repair and atone. Sometimes the need is acted on, sometimes it’s ignored; other times it’s merely presented, and the ending is unresolved.

The cosmos is governed by powers far greater than our own, these songs suggest. Difficulties are eternal and consolation temporary, found only in humble pleasures. This is all framed in a kind of rural, retrograde religiosity. Against these chastened, mythological songs, Vietnam, civil rights, and all the rest shrink in significance. Todd Gitlin writes about what I’m trying to say here at the end of his book The Sixties. “Musical imagination … was trying to conjure a separate peace. The personal and muted was more appealing than the political and outré. No more floating free in far out space.” With John Wesley Harding as a model, the sympathetic followed suit: The Byrds with Sweetheart of the Rodeo and The Band’s first two records, the second of which included their hit, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.”

I bring this up because of a lively discussion held some time back on the S-USIH Facebook page as to whether “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” is a Lost Cause song. It is, but to say that it is doesn’t say enough. It speaks to what’s troubling about the move toward the cosmic interior. The line between sympathizing with the opposition and supporting it begins to blur.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Paul Nelson had the best description of the album in his review of Nashville Skyline:

In (John Wesley) Harding, Dylan superimposed a vision of intellectual complexity onto the warm, inherent mysticism of Southern Mountain music, rather like certain French directors (especially Jean-Luc Godard) who have taken American gangster movies and added to them layers of 20th-century philosophy. The effect is not unlike Jean-Paul Sartre playing the five-string banjo. The folk element gains a Kafka-esque chimericality, and the philosophy a bedrock simplicity that leaves it all but invisible and thus easy to assimilate. “Down Along the Cove” and “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” exceptions to the above and the record’s last two songs, are almost a microcosm of the geography to come.

forgot. album was released December 27, 1967

Andrew, you’re right, that Nelson description of JWH is a terrific one, though I’m not sure I can go along with the Sartre/banjo line. Thanks for sharing it. As for the official December 27, 1967 official release date–yes, that’s correct, but in regard to my argument, a technicality. My understanding is that this record hit stores in the new year. One source says February. I think it’s safe to say, in terms of reception, this was a 1968 record. Also, Columbia did very little to promote it, at Dylan’s request. In any case, there’s a whole lot more to this that I don’t get into. What Dylan was doing during much of 1967, out of the public eye, prior to the recording of JWH–producing a great deal of music, it turns out–is one of the most important parts of his story.

Agreed there’s a whole lot more but what is it and what’s it worth.

Anyway, not sure that facts are technicalities, I think of them more as historical building blocks or foundations.

“. . . The Band’s first two records, the second of which included their hit, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” except “though not a chart hit for The Band, ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’ did become a popular radio track, before the song’s first cover, by Joan Baez, went Top Five in 1971.

“The classic cinema verité documentary, Don’t Look Back, captures the beginnings of this manic period.” I think Eat the Document is more about and does a better job at showing this from the opening snort to the end.

“Dylan didn’t want his message pre-ordained; he didn’t want his topics restricted to “protest”; he wanted to express himself freely.” His topics never were restricted; just think of the love songs and transcendental things he wrote during that early period. Anyway I’m not sure Bob ever wrote protest songs the way Phil Ochs wrote them

“So it’s not hard for me to imagine the excitement surrounding the releases of artists such as Dylan and the Beatles in the sixties and to feel them in real time as commentaries on each other.” The release of an album was a much different kind of event in the 60s than it is now. In the documentary It was Twenty Years Ago Today, Paul McCartney and Roger McGuinn talk abut this kind of competition or communication with songs,

Also not sure of what a “1968 album” is: Anthem of the Sun. Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Music From Big Pink. The White Album. Astral Weeks, Beggar’s Banquet?”

Have read literally hundreds of books about Dylan and have never seen anything mentioned about JWH not being available until February 1968.

Maybe Bob just wanted to see if he could do an album of song without choruses.

Ever seen the Watchtower that overlooks Lake Mohonk in New Paltz, New York, (near Woodstock). Bob probably drove by it once or twice maybe. Maybe he was imagining stories taking place in and around that Watchtower. Who knows. Maybe Ricks.

Maybe it has nothing to do with how the song-poem makes you feel, which is its real importance. This ain’t Paradise Lost after all.

The basement and Woodstock were important for a number of reasons

Andrew, I appreciate these observations. There are many directions from which to come at this topic. I can see that you write from a good deal of expertise. By the way, we’re always looking for guest posts at the blog if you ever have something you’d like to submit.

As for the issue of the release date, it’s hardly worth arguing about. A couple of your comments, however, verge on accusing me of not understanding what a fact is or even of making stuff up. Maybe you didn’t mean it that way, but let me offer a few quotes in my defense …

“When it finally appeared in February 1968,” writes Andy Gill of JWH in Bob Dylan: Stories Behind the Songs 1962-69 (Carlton, 1998), “psychedelia was at its floral peak …” The Dylan Companion, edited by Elizabeth Thompson and David Gutman (Delta, 1990) refers to JHW as Dylan’s “1968 album.” “By the time John Wesley Harding was released in 1968, the hostile youth …,” writes David Yaffe in Bob Dylan: Like a Complete Unknown, (Yale UP, 2011).

Of course, as you point out, there are hundreds of books on this topic, and many refer to late December, 1967, if not the official (whatever that means) date of December 27, 1967. On the other hand, The Bob Dylan Complete Discography, compiled by Bruce Hinton (Universe, 2006), lists the record this way:

John Wesley Harding

US Release January 1968

UK Release February 1968

But this is hardly worth arguing about because it’s beside the point. I’m not making a claim about an official release date. I’m talking about the record in the context of its initial reception. The chronological facts that would apply in this case would be answers to questions like, When was it generally available in stores? When did it first chart (March 1968, says one source)? Were any singles released, and when? When was it reviewed? I don’t have these dates at my fingertips, but logic suggests that they would not likely be the last five days of 1967 but would be distributed over the several months of 1968. That’s what I meant by “a 1968 record.” And in any case, however you measure this, the record is fifty years old.