Editor's Note

This is one in a series of posts examining The American Intellectual Tradition, 7th edition, a primary source anthology edited by David A. Hollinger and Charles Capper. You can find all posts in this series via this keyword/tag: Hollinger and Capper.

This post examines some of the texts included in Volume II, Part One: Toward a Secular Culture. Here are all the texts included in this section:

Asa Gray, selection from “Review of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1860)

Thomas Wentworth Higginson, selection from “A Plea for Culture” (1867)

Charles Peirce, “The Fixation of Belief” (1877)

William Graham Sumner, “Sociology” (1881)

Charles Augustus Briggs, selection from Biblical Study (1883)

Lester Frank Ward, “Mind as a Social Factor” (1884)

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, “The Solitude of Self” (1892)

Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” (1893)

Mark Twain, “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses” (1895)

William James, “The Will to Believe” (1897)

Josiah Royce, “The Problem of Job” (1898)

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Selection from Women and Economics (1898)

Henry Adams, “The Dynamo and the Virgin” (1907)

George Santayana, “The Genteel Tradition in American Philosophy (1913)

There are eras of U.S. history that set the table for the crucial debates and signal events that came immediately after them. Then there are eras of U.S. history that remodel the whole damn kitchen. The readings in the first section of Volume II of Hollinger and Capper – and, for that matter, the second section — come from the latter sort of era. And we are still cooking in that kitchen.

This is my favorite era to teach in the second half of the survey: this dizzying period of rapid epistemic, social, economic and cultural transformations between, oh, 1880 and 1920, or (more broadly) 1877-1924. We Americanists periodize this, clumsily, as “The Gilded Age and Progressive Era,” though “The Dawn of American Modernity” would work. I like Daniel Borus’s characterization best: this is the age of “Multiplicity,” modernity’s unmistakable calling card.

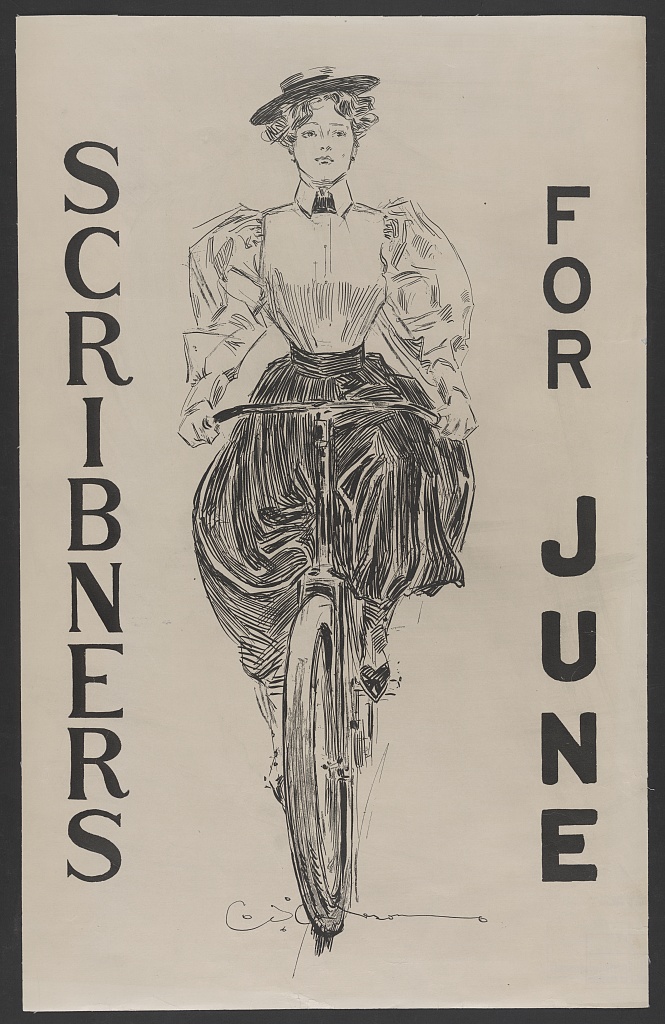

In this time period, as Susman noted, we witness the shift from character to personality. We see the New Woman on the cover of Scribner’s magazine, serenely riding her bicycle into the future. We get Houdini and Buffalo Bill and body-building and the Y.M.C.A. and basketball and Billy Sunday. We get burgeoning labor activism arrayed against the tentacles of the monopolist octopi, each arm of the monsters wielding the power of the state to protect their interests. We get Plessy v. Ferguson, alas, and Jim Crow settles in for a long, awful tenure — but also there is the New Negro, the NAACP, Garveyism, the Great Migration, the Harlem Renaissance.

We hear a genial and generous and humorous if occasionally moody invitation to the quest for truth from William James, a slightly more irascible call to the same from Charles Peirce, and the ever-hopeful democratically scientific and scientifically democratic exhortations of John Dewey, our Mr. Rogers avant la lettre. We get Santayana the cultured European cosmopolitan sneering at the effete effeminacy of the genteel tradition, as irony dies and is reborn again and again and again via the dynamo of modernity.

We stand amidst the explosion in the shingle factory. This was an unplanned kitchen remodel accidentally accomplished – or at least commenced – with dynamite.

Speaking of kitchens — as Elizabeth Cady Stanton does in her essay “The Solitude of Self,” which I discuss in more detail below — I just ordered a tiny dinette set from Amazon, a very small table and two straight-backed chairs, flat-pack furniture that I can haul in my car and put together by myself with an Allen wrench. This is one of many pieces of furniture-by-mail I will be receiving in the next few weeks as I get ready to split my time between our home and my pied a terre in Stephenville, Texas.

I have been hired as a Visiting Assistant Professor of History at Tarleton State University. It is a one-year appointment. This fall I’m teaching both halves of the survey, including an honors section of the second half. In addition to The American Yawp

, I’ll be assigning three monographs: Jackson Lears, Rebirth of a Nation; Mae Ngai, Impossible Subjects; and good old Andrew Hartman, A War for the Soul of America. In the spring I’ll be teaching some combination of survey sections and one 4000-level seminar on the History of American Education. (I haven’t settled that reading list yet – suggestions always welcome.)

I am very, very happy to have landed this job. I hope it turns into something more permanent, but I’m just glad I get to teach and write and join new colleagues and make new friends.

And truth be told, I would not have to schlep this furniture and assemble it all by myself. My wingman is ready to lend a hand, my folks would help me if I asked, my kids would help me. But after 25-plus years of marriage, three cross-country moves as a trailing spouse, innumerable compromises to (wisely and willingly) accommodate the career of the marriage partner with the higher earning power and the more stable job – after all that living, which has been so busy and so noisy and so pleasantly if exhaustingly kinetic, it was more satisfying than I expected it to be to hunt for my own apartment and file a lease application based on my own income and sign a lease with my own name alone as guarantor of payment.

So now, at the age of not-quite-fifty, I am furnishing my own apartment to suit my tastes and my needs alone – something I’ve never done before. During the few years when I lived alone or rented a room I lacked either the need to furnish my own place (think ratty, abandoned furnishings from the previous tenants) or the means to do so (think a pallet of blankets on the floor in lieu of a bed / sofa).

My 4-days-per-week of solitary living to suit my own schedule may be real enough, but absolute independence or isolation is really theoretical. Elizabeth Cady Stanton understood this in her speech on “The Solitude of Self,” included in this section of Hollinger and Capper. “In discussing the rights of woman,” she wrote, “we are to consider, first, what belongs to her as an individual, in a world of her own, the arbiter of her own destiny, an imaginary Robinson Crusoe, with her woman, Friday, on a solitary island. Her rights under such circumstances are to use all her faculties for her own safety and happiness.”

Stanton argues that women should be well-equipped to fend for themselves in life, because often they have to, and those who do not have inner resources to fall back on are “ground to powder.” She argues that women deserve to stand alongside men with the same opportunities, the same educations, the same standing as citizens and activists. She makes this argument in the language of democratic liberalism – self-sovereignty and equality – but also (though to a lesser extent) on the basis of biological difference. Women have a right to equal standing because of the experience that they and they alone must face: “Whatever the theories may be of woman’s dependence on man, in the supreme moments of her life, he cannot bear her burdens. Alone she goes to the gates of death to give life to every man that is born into the world; no one can share her fears, no one can mitigate her pangs; and if her sorrow is greater than she can bear, alone she passes beyond the gates into the vast unknown.”

Most of Stanton’s argument is based on common experiences of life which might fall by chance on men or women. But here she plays the Queen of Spades — not quite as terrifyingly as Pushkin does, but pretty dang close: if [some, most?] women are able to face the grim and (at that time) very real prospect of death in childbirth, they are certainly capable of facing all the other vicissitudes of life on equal footing with men.

The idea was not that every woman was or should be a Robinson Crusoe – or, remembering today the recent passing of the great American literary scholar Nina Baym

, not every woman had to be a Natty Bumppo or Thoreau at Walden (and let’s be real, the solitary Thoreau in Waldenwas a character as fictional as Crusoe). But every person should be equipped to survive on their own if necessary.

This fully-realized capacity for self-reliance, Stanton argued, would be for the good of society – that emerging world of multiplicity, of plurality, of perspectivalism, a world becoming too complicated for any single person or small group of people to understand or shape without help. To avoid social shipwreck, to avoid a world of stranded Robinson Crusoes, required all hands on deck: “Seeing, then, what must be the infinite diversity in human character, we can in a measure appreciate the loss to a nation when any class of the people is uneducated and unrepresented in the government.” This is yet another argument for pluralism – every human has a unique perspective and personality to bring to bear on the problems facing society. So the more inclusive our society becomes, the more wisdom becomes available to all for the common good. If we care about the collective good, we must care about the individual right of each person to fully flourish.

That is a very liberal argument and a very Pragmatic argument, which is no doubt in part why I like it. Looking back at the generations of women in my own family – back as far as the women who were very old ladies when my grandmothers were little girls, which is as far back as my inherited memory goes – I can trace the long, slow struggle of generations of mothers and grandmothers, aunts and nieces, sisters and girl cousins, to attain the conditions in which they and their sisters and their daughters could fully flourish.

I am in a good place – two good places, actually – not only to flourish, but to help create and sustain the conditions for others to flourish as well. For a few days a week, I’ll live in Stephenville and focus on the needs of my students and the goals of my colleagues and the aims of my own career. And for a few days a week, I’ll live in our enormous and newly-busy house in suburbia – home now not only to the two of us (a well-matched pair well-used to one another) and to our youngest child, but also to my oldest niece who has come to live with us while going to college, and (soon) my oldest child and their spouse-to-be, who will be staying with us for a few months after their marriage while they save up money for a home of their own. (We’ve got the square footage to spare; what we don’t have is a huge wad of cash.)

Reader, I cannot tell you how much joy it brings me to embark on this new stage of life – to be able to welcome new family into our household, to make room for the rising generation, to be “home base” for these bright young people preparing to strike out on their own. No Robinson Crusoes here; more like Swiss Family Robinson.

And for that very reason, reader, I cannot tell you how unbelievably grateful I am to have landed a job that will take me out of town four days a week to enjoy a little solitude of self.

0