Editor's Note

Today we have a new post in Matthew Linton’s series on the intellectual history of country music. Matt has previously written about gender, empire, and class, and today he looks at the history of Black country musicians as they encounter or evade the issues raised by performing in a genre that has historically been coded as (very) white.

Previous posts in this series have been:

- Can a Country Girl Still Survive? Female Country Musicians as Chroniclers of Rural Poverty

- Good Wives, Honky Tonk Angels, and Cuckolded Cowboys: The Feminisms of Kitty Wells, Tammy Wynette, and Nikki Lane

- Countrypolitan Nationalism: Ernest Tubb and Hank Snow’s Audiopolitics of Empire

Matt is graduating (this weekend!) from Brandeis University. His dissertation, Understanding the Mighty Empire: Chinese Area Studies and the Construction of Liberal Consensus, “traces the development of university China studies and its relationship to the New Deal-style liberal politics between 1930 and 1980.” For more information, please visit his website.

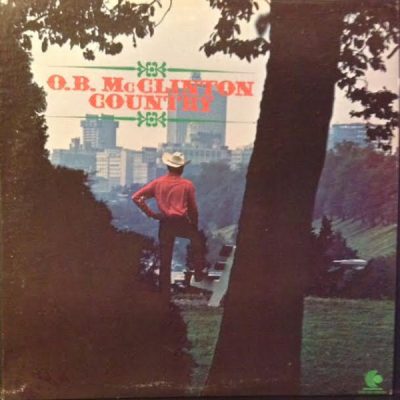

In 1987, country music novelty singer O.B. McClinton released “The Only One

In 1987, country music novelty singer O.B. McClinton released “The Only One

” which explored the complexity of being a black country music artist. The song told the story of McClinton traveling to a country bar to sing, only to be questioned for being a black artist in a genre dominated by white artists. He told one particularly antagonistic bar patron, “I’ve always been country/though Lord my skin is black” and when he was told he was no Hank Williams Jr. – who had risen to prominence during the 1980s peddling a white supremacist version of outlaw country – he responded by complimenting Williams as “what a singer” though noting that he was a different breed from Williams, “the only one,” a black country artist. Naturally, McClinton wins over his antagonist through his adherence to the country tradition and talents as a singer. They have a drink symbolizing McClinton’s acceptance by white country audiences.[1]

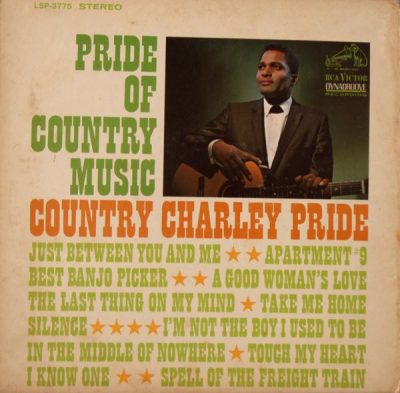

“The Only One” is not simply a racial parable, however, but also a winking reference to another, more famous, black country musician: Charley Pride. Though his most successful years were behind him, Pride was country music royalty by 1987. Between 1968 and 1980, Pride was one of Nashville’s commercial juggernauts; scoring eight number one country hits between 1968 and 1971 alone. During that time, he won three Grammys, three American Music Awards, and three Country Music Association honors along with becoming the first African American man to perform at the Grand Ole Opry since DeFord Bailey in 1941. “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin’” (1971) even crossed over to pop radio reaching number twenty-one on the Billboard charts in 1972. It has become a country classic and has been covered by a host of country legends including George Jones, Conway Twitty, and Alan Jackson.

Ironically, given his status as the only prominent black country artist, Pride’s success was owed to his ability to bridge divisions between country traditionalists (termed “hard country”) and an emerging country-pop fusion (called “soft country”). Pride respected his country forefathers and faithfully covered classics like Hank Williams’ “Kaw-liga.” At the same time, his biggest hits incorporated lyrical themes and musical styles from soft country. Most of his lyrics were about love, jettisoning the honky-tonks and cowboy and railroad tropes of his hard country contemporaries. Though his songs foregrounded the guitar, Pride incorporated the lush strings and female background singers that defined soft country crooners like Ferlin Husky.[2] Every country music fan could find something recognizable in Pride’s music and this universality allowed him to cross the “musical color line.”[3]

Ironically, given his status as the only prominent black country artist, Pride’s success was owed to his ability to bridge divisions between country traditionalists (termed “hard country”) and an emerging country-pop fusion (called “soft country”). Pride respected his country forefathers and faithfully covered classics like Hank Williams’ “Kaw-liga.” At the same time, his biggest hits incorporated lyrical themes and musical styles from soft country. Most of his lyrics were about love, jettisoning the honky-tonks and cowboy and railroad tropes of his hard country contemporaries. Though his songs foregrounded the guitar, Pride incorporated the lush strings and female background singers that defined soft country crooners like Ferlin Husky.[2] Every country music fan could find something recognizable in Pride’s music and this universality allowed him to cross the “musical color line.”[3]

References to race have been conspicuously absent from Pride’s music from the beginning of his career until today. Unlike McClinton who called himself “the Chocolate Cowboy” and joked about his exceptional status as a black country artist, Pride cultivated a colorblind narrative of his upbringing that studiously avoided his blackness while tying him to a stock story of economic uplift shared by many of his contemporaries. Born to sharecroppers in Mississippi, Pride first gained attention for his athletic exploits, pitching for several Negro League baseball teams during the 1950s. After a series of injuries ended his career, he moved to Montana working construction while singing at local bars and honky-tonks. He quickly outgrew the small Montana music scene, moving to Texas in 1967. He claimed race never hindered his musical career. “But people didn’t care if I was pink,” Pride said in a recent interview, “RCA signed me, and all of the bigwigs, they knew I was colored, but unanimously they decided that they were still going to sign him.”[4] These claims are despite evidence that RCA withheld Pride’s race from promoters and radio DJs because they feared racism would limit Pride’s ability to reach a wide country audience.[5] In the same vein, Pride’s face was not featured on his first several records as RCA hoped to keep his race a secret from record buyers. As historian Charles Hughes notes about Pride and colorblindness, his success as a black musician in a genre dominated by whites demonstrated “country listeners’ racial tolerance and the Nashville industry’s open-minded professionalism” even in an era of widespread white backlash against integration and racial equality.[6]

It was not race, but class, that Pride claimed was his primary barrier to music success. Like his contemporaries Dolly Parton and Loretta Lynn, Pride spoke of a childhood growing up in grinding poverty in the rural south. He bought his first guitar at age fourteen after he was drawn to country music when hearing Hank Williams, but financial needs compelled him to pursue athletics and, later, construction. Emphasizing the primacy of class, allowed Pride to foreground commonalities with other country artists (as well as many country music listeners) and to sidestep fraught discussions of race. In other words, Pride was just another poor southerner made good.

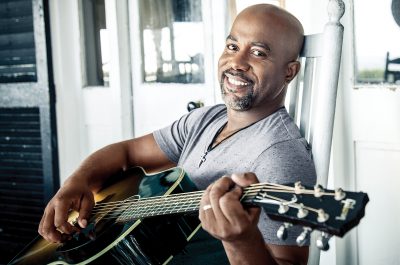

Pride’s stardom and acceptance by the white country music establishment crafted a colorblind narrative that other black musicians could follow. A famous recent case where race and country music intersect involves former Hootie and the Blowfish frontman, and multi-platinum country music star, Darius Rucker. Rucker pivoted to country music after the popularity of Hootie and the Blowfish waned in the early 2000s and he released two failed neo-soul solo albums. His album Learn to Live (2008) went platinum and made him the first African American musician to top the Billboard country music chart since Pride in 1983. In 2009, Rucker became only the second African American artist to win a Country Music Award in a major category. Like Pride, Rucker’s success hinges upon his music’s ability to create a broad country music consensus between younger-skewing pop-country (sometimes called “bro-country”) and adult contemporary audiences. Rucker’s hit singles, including “It Won’t Be Like This for Long

Pride’s stardom and acceptance by the white country music establishment crafted a colorblind narrative that other black musicians could follow. A famous recent case where race and country music intersect involves former Hootie and the Blowfish frontman, and multi-platinum country music star, Darius Rucker. Rucker pivoted to country music after the popularity of Hootie and the Blowfish waned in the early 2000s and he released two failed neo-soul solo albums. His album Learn to Live (2008) went platinum and made him the first African American musician to top the Billboard country music chart since Pride in 1983. In 2009, Rucker became only the second African American artist to win a Country Music Award in a major category. Like Pride, Rucker’s success hinges upon his music’s ability to create a broad country music consensus between younger-skewing pop-country (sometimes called “bro-country”) and adult contemporary audiences. Rucker’s hit singles, including “It Won’t Be Like This for Long

” and “Come Back Song,” are about universal themes of love and loss.[7] It’s telling that Rucker and Pride have become friends with Rucker acknowledging in a recent interview that he consults with Pride about how to navigate the challenges of being a black man in country music.[8]

A polarized political climate and the ubiquity of social media have made it difficult to skirt issues of race and country music, however. After persistent racial harassment from a Twitter user in 2013 telling him to “leave country music to white folk,” Rucker shot back calling the user an “idiot” and taunting them with his Grand Ole Opry membership. Rucker tried to downplay the incident, saying it was not representative of country music fans, but did acknowledge that racist harassment had followed him throughout his career. While Rucker has been applauded for his willingness to chastise racists on social media, he has been criticized for his willingness to associate with accused racists in the name of a shared Southern identity. As Amanda Petrusich noted in a recent piece in The New Yorker, Rucker cast members of the reality television show “Duck Dynasty” in his music video for “Wagon Wheel” despite the patriarch Phil Robertson’s racist comments to GQ magazine.[9] Both incidents show the difficulty of sidestepping race when you’re a black country musician with a predominantly white audience.

Kane Brown

How Rucker navigates the pitfalls of being a black country star will be instructive to a rising multiracial generation of country stars like Kane Brown and Lindi Ortega. Just as social media has complicated country music’s colorblindness, it has also eroded the hard genre definitions that allowed country’s whiteness to persist. Americana, with its close ties to traditional black American music like blues and soul, has absorbed many of country’s most promising young independent voices. On the other end of the spectrum, hip-hop and pop influence has crept into pop-country fueling cross-over hits like Maren Morris’ “The Middle,” Justin Timberlake’s “Say Something,” and Kane Brown and Camilla Caballero’s “Never Be the Same.” Even Beyonce has tried to cross-over with “Daddy Issues,” a collaboration with The Dixie Chicks. With this new influx of diverse talent into country music, it stands to reason that Rucker will no longer be “the only one” and instead one of many.

Notes

[1] There’s a brilliant inverse of this song by Latimore, a soul artist during the 1970s, called “There’s a Redneck in the Soul Band” (1975) which depicts a black audience stunned by a funky white boy playing in a predominantly black soul band. For a fascinating discussion of this song and its racial symbolism see, Charles L. Hughes, Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American Soul (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015): 1-3.

[2] His cover of “Mountain of Love” (1981) was probably the apogee of his soft country sound.

[3] Hughes, Country Soul, 15.

[4] Brian D’Ambrosio, “For Charley Pride, Red Ants Festival will be a homecoming,” Last Best News (July 24, 2014): http://lastbestnews.com/site/2014/07/for-charley-pride-white-sulphur-festival-will-be-a-homecoming/. (Accessed December 26, 2017)

[5] Country Music Hall of Fame, “Charley Pride,” https://countrymusichalloffame.org/artists/artist-detail/charley-pride.

[6] Hughes, Country Soul, 129-130.

[7] He has also excelled in two of the most important areas in the era of music streaming: covers and Christmas music. Rucker’s most streamed song on Spotify (by 100 million streams no less) is a cover of Old Crow Medicine Show’s “Wagon Wheel” and songs from his album “Home for the Holidays” is featured on many of Spotify’s most popular Christmas playlists.

[8] Joe Bargmann, “Will Darius Rucker Break Country Music’s Color Barrier Once and for All?” Dallas Observer (July 5, 2016): http://www.dallasobserver.com/music/will-darius-rucker-break-country-music-s-color-barrier-once-and-for-all-8445362. (Accessed May 6, 2018)

[9] Amanda Petrusich, “Darius Rucker and the Perplexing Whiteness of Country Music,” The New Yorker Magazine (October 25, 2017).

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Matt, thank you so much for this post. As music literacy goes, I’ve been playing catchup most of my life — except for hymnody and schlocky Christian radio from the 70s and 80s. Fortunately for the first, unfortunately for the second, I am more than literate.

Anyway, I was in grad school before I learned the term “blue-eyed soul” — had no idea Van Morrison was an Irish dude. [No worries — I have since listened to more Van Morrison than my heart can bear.] So I always appreciate a real connoisseur’s overview of a genre or subgenre.

I wonder if you could comment on how the critical reception of Charley Pride in his genre compares with the reception of, say, Teena Marie in her genre. My guess is that even among those whose interest is purportedly the art itself, Charley Pride has had the tougher time of it. But I don’t know. Hoping you do!

Blue-eyed soul was the Righteous Brothers if Shindig! means anything. It was racial code for white singers who sounded black.

It was Bob Dylan who wrote “Wagon Wheel.” He wrote it for the Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid soundtrack. It wasn’t used and never finished. Dylan wrote it under the title “Rock Me Mama.” The guy from Old Crow added to it much later. Dylan wrote it in 1973. You can find it on many Dylan bootlegs of the Pat Garrett sessions such as Peco’s Blues.

I might go so far as to argue that there is no longer any such thing as what used to be known as country music. It’s suburban faux semi-rural music that comes from under a cowboy hat in a subdivision and all sounds the same. That’s just me.

Think I’ll go dust off my Carter Family records. A jolt of “Mystery Train” is just what i need.

Hi LD,

Thank you for the thoughtful comment. I am not an expert in Teena Marie by any measure, but I will try to answer your question about critical reception as best I can.

Pride’s critical reception was initially positive, but has faded over time. As I mention briefly in the piece, Pride’s success came from his ability to satisfy hard country and soft country audiences. This included critics who were won over by his blending of traditional and pop sounds. Pride’s race could have been career ending, but his label hid his race from country DJs and record store owners. By the time most critics became aware of Pride’s race, they were already fans of his music. Pride, for his part, was more than willing to meet critics who may have harbored racist attitudes halfway. He downplayed racism in the country music industry and pursued this colorblind narrative discussed above.

Though Pride was a critical darling during the 1970s, his place as a black country musician is often more remembered than his music. Despite piling up hits in the 1970s and early 1980s, “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin'” remains his only classic country song. His blend of hard and soft country was influential in spurring the late 1980s boom with artists like Garth Brooks and Alan Jackson combining traditional lyrics with pop production. Still, since his peak was between eras and he was not representative of a larger movement (like Waylon Jennings and Outlaw Country, for example), Pride’s music has declined in influence during the 2000s.