Editor's Note

This is one in a series of posts examining The American Intellectual Tradition, 7th edition, a primary source anthology edited by David A. Hollinger and Charles Capper. You can find all posts in this series via this keyword/tag: Hollinger and Capper.

This is the first post in a series devoted to reading and discussing both volumes of The American Intellectual Tradition (7thedition). This primary source collection, familiar to many a professor and student of American intellectual history, has been shaped by the careful editorial hands of David A. Hollinger and Charles Capper.

As part of the 2012 state-of-the-field forum published in Modern Intellectual History, David Hollinger contributed an essay explaining the reasoning that he and Charles Capper used in selecting the readings for the sixth edition of this work, and discussed the problems and challenges of choosing among many suitable alternatives. Thankfully, Professor Hollinger has made that essay freely available as a .pdf – you can access/download it via this link.

I encourage everyone to read that essay, not only for its applicability to our discussions here, but also as a valuable case study in the intellectual labor that goes into shaping anthologies more generally.

Anthologies – much like syllabi — are made, not found, and to construct an anthology is to carve a particular path through a field of inquiry. Sometimes that might mean following already deeply-scored trails, and sometimes that might mean striking out in a different direction. In this anthology, the editors do a little of both. As a result, Hollinger and Capper have very ably marked out a

trail through American thought, anAmerican intellectual tradition involving the contestation between faith and reason, piety and secularism, selfhood and the social order. If we choose to go in different directions – new directions, perhaps? – we are still profoundly grateful for the work already done. One has to start somewhere.

In fact, in this post I invite our readers to consider the starting point selected by Hollinger and Capper, and to speculate on what might happen to the path if we were to start the journey with a different thinker, or at least with a different text.

The first text in the anthology is John Winthrop’s now-famous 1630 sermon aboard the Arbella, known as “A Modell for Christian Charity.” This is the city-on-a-hill sermon, yes – but also the “Sweet sympathie of affeccions” sermon, the “some must be rich some poore” sermon. It is, in short, a densely tangled knot of several ideas that governed the choices of the first governor and other authorities of the Massachusetts Bay Company’s settlement.

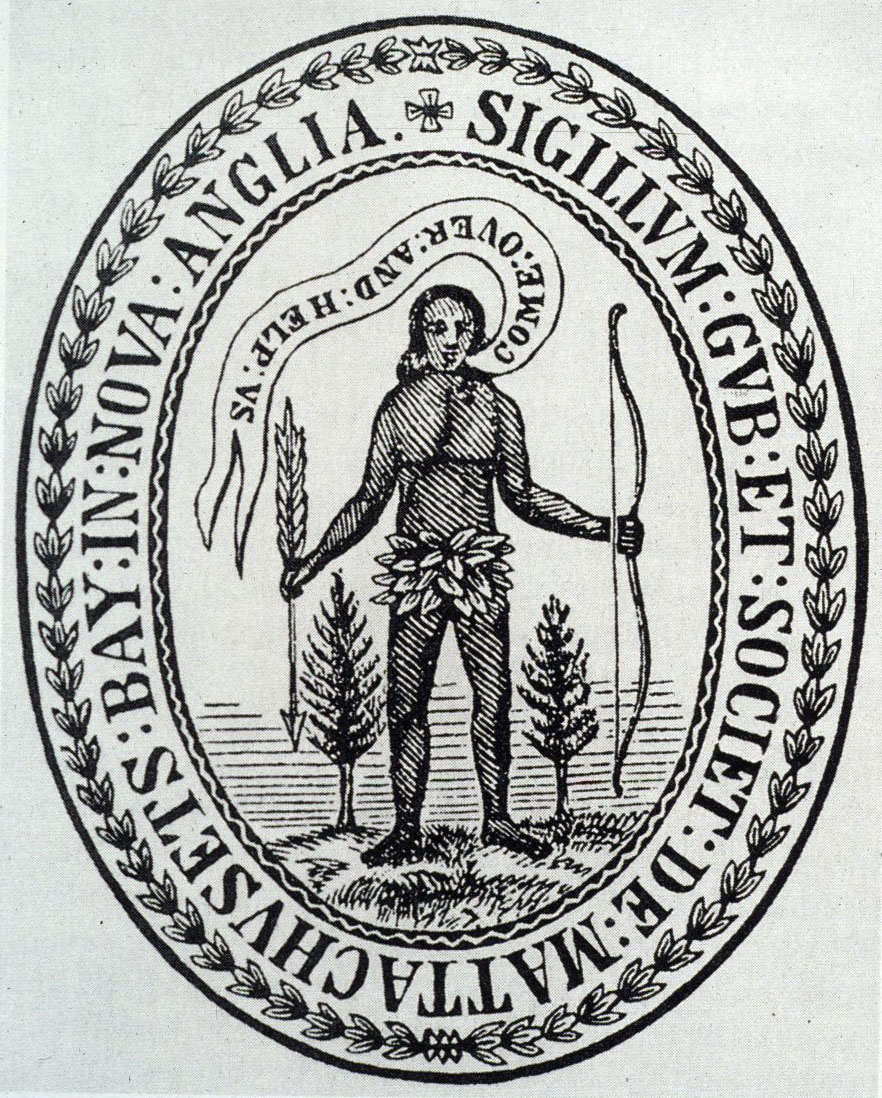

The Massachusetts Bay Company Seal (1629), courtesy of UC Davis

But does “the American intellectual tradition” start with the Massachusetts Bay Company? Should it? Beginning the anthology here is very much in keeping with the intellectual tradition of American intellectual history as an established field – Perry Miller’s framing of “the errand into the wilderness” casts a long shadow. But the foray of the Puritans in 1630 was not the first foray of English settlers to North America, or to that part of North America that eventually became the United States America, and certainly not the first foray of European settlers who managed to carve out a permanent city on what passed for a hill. I speak, of course, of St. Augustine, the oldest settlement founded by Europeans that has been continuously occupied ever since, established by the Spanish in 1565 as a base from which to pry off other European attempts at settlement, including the ill-fated Fort Caroline, a French outpost the Spanish sacked and destroyed when the palisades of St. Augustine must have been still oozing sap from being cut down in the swampy, mercilessly hot and humid paradise of La Florida.

However, while St. Augustine is perhaps a good place to begin in discussing European settlement of (what became) the United States, it is probably not the best place to start tracing out “the American intellectual tradition,” because the documents written in connection with that founding or the administration of that colony probably did not make their way into wide circulation, or even wide discussion, among the waves of settlers coming from England in the decades to follow. Those documents are housed in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, Spain. (The PBS “Secrets of the Dead” episode on La Florida is outstanding, and I would recommend it for anyone teaching the first half of the survey.)

Well, no one expects the Spanish Inquisition, and perhaps no one expects that the American intellectual tradition would begin not in English but in Spanish – though perhaps we should! Nevertheless, even setting aside the beginnings of a continuous European presence in North America and how writing from that or aboutthat settlement would have shaped the ideas of Anglo-American colonizers, it seems to me that 1630 is awfully late to begin the journey through American thought.

So where – or, rather, when – should one start instead?

I suggest starting in the 1580s, when Richard Hakluyt the elder and Richard Hakluyt the younger were both actively promoting the idea of planting an English settlement in North America. Hakluyt the elder’s 1585 pamphlet, Inducements to the Liking of the Voyage Intended towards Virginia in 40. and 42. Degrees, lays out an argument for settlement that is by turns missiological, mercantilist, virulently anti-Catholic, and imperialistically militant in scope.* Hakluyt provides a handy summary of his argument for a colony near the end of the document:

The ends of this voyage are these:

- To plant Christian religion

- To trafficke.

- To conquer.

Or, to doe all three.

There is the regnant conception of “America” that shaped attempts at English settlement and guided the English presence there for decades before the Pilgrims landed in 1620 or the Puritans landed in 1630. America (including Native peoples) was to be an outpost of Protestant Christianity, America was to be a source of enriching trade and strategically useful natural resources, and America was to be a foothold for an English empire.

Those three ideas strike me as equally important in shaping American thought and American culture. Those were for the most part the founding principles of what eventually became America, and they certainly run through “American thought” from 1607, when Jamestown became the first English settlement that would endure (barely) in the land.

Some of those ideas run through the sermons of John Winthrop as well. Before Winthrop preached aboard the ship to the group of settlers destined to found the “city on a hill,” he first had to persuade people to sign on to the Massachusetts Bay Company’s proposed venture. In 1629, Winthrop preached a sermon entitled “Reasons to Be Considered for Justifying the Undertakers of the Intended Plantation in New England and for Encouraging Such Whose Hearts God Shall Move to Join with Them in It.”** In this sermon, he lays out the logic undergirding the founding of the colony.

First, Winthrop says, “it will be a service to the Church” to plant “true religion” in North America as a bulwark against the satanic teachings of “the Jesuits.” As important as anti-Catholicism has been in American thought and life practically to the present, it is useful to acknowledge its presence earlier in the American tradition rather than later. From a brief for Protestant Christianity (of a Puritan sort, of course), Winthrop moves immediately to the economic reasons for the settlement: “This land growes weary of her Inhabitants…” There is no economic opportunity in England. There is rising poverty, rising vagrancy, the increasing enclosure of land, and no room for the growing population. But, Winthrop argues, there’s plenty of room in America. “[W]hy then should we stand hear striveing for places of habitation…and in ye mean tyme suffer a whole Continent, as fruitfull & convenient for the use of man to lie waste without any improvement.” Why indeed.

In that argument we see one of the most crucial ideas shaping American life from the beginnings of colonization: the conception of what is “waste” land, ripe for the taking, and what is someone else’s property. Ownership of the land is tied to the labor of improving it, and in that sense, the colonizers argued, they had a right to any land the Native people had not brought under cultivation or development. Winthrop makes this argument explicit later in the sermon when he sets up and then knocks down possible counterarguments to the venture of settlement. In fact, that is “objection 1”: “We have noe warrant to enter upon that land which hath been so long possessed by others.” Here we see at least the recognition of an argument that might give the would-be settlers pause: we would be interlopers laying claim to land that belongs to others. Not to worry, though, says Winthrop; it’s not reallytheirs: “That which lies common & hath never been replenished or subdued is free to any that will possesse and improve it…” This idea undergirds not only the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, but the conquest and settlement of every inch of the North American continent. “The land was ours before we were the land’s…” Thus spake the New Englanders…and the Virginians, and the Carolinians, and the Tennesseeans, and the Nebraskans, and the Californians.

Not all the New Englanders, though. Hollinger and Capper include a dissenting voice – well, actually two dissenting voices – in this first section of the anthology. We have Anne Hutchinson, on trial primarily for not only slandering a good number of the ministers of the colony but also for proclaiming heretical ideas. And we have Roger Williams, banished from the colony primarily for his dissenting ideas about religious freedom. It’s worth remembering, though, that in addition to asserting their own religious liberty, either by its exercise or by its theoretical defense, both of these dissenters were also in opposition to the Pequot War. American thought has grappled from the outset with the questions of who is a person, who is an American, and to whom “America” belongs.

Roger Williams asserted a radical answer to all three of those questions in The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience (1644), excerpted in Hollinger and Capper. In his discussion of civil peace, he remarks that “so many glorious and flourishing cities of the world maintain their civil peace; yea, the very Americans and wildest pagans keep the peace of their towns or cities…the peace spiritual, whether true or false, being of a higher and far different nature from the peace of the place or people, being merely and essentially civil and human” (46). Whatever “American” has come to mean in the history of thought, for Roger Williams, it was the name for the Native people usurped from their place by the Puritans who embraced the idea that land belonged to anyone who “improved” it in a way recognizable and familiar to Europeans.

There is perhaps no more consequential idea in the history of America. I say “perhaps,” because the idea of a chosen people with a divine mission is also quite consequential in the history of America. It is difficult to say which has been the more significant in shaping subsequent conceptions of the social order. Indeed, that might be a fruitful avenue of discussion. But both ideas were crucial to the founding and growth of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and both ideas are emphasized in Winthrop’s 1629 sermon, whereas only one of these ideas comes through clearly in the 1630 sermon.

I am not suggesting that Hollinger and Capper should replace one sermon with the other, nor am I suggesting that they should add one sermon alongside the other. If they did that, who would get the boot? (My vote goes for Charles Chauncy, bless his heart.) And in this series of posts, my own approach will be not so much to posit that there are other texts that shouldbe included in Hollinger and Capper’s anthology – it is, after all, theiranthology, and they have their own criteria of selection – as to consider what texts might be included in an anthology representing American intellectual life from colonization to the present. There is not one American intellectual tradition; there are American intellectual traditions, radiating out in all directions at every point along the pathway. In this series of posts, let’s consider together what might be the consequences of following some of those paths.

If you would like to contribute an essay to this series, feel free to contact me or any of our bloggers. All of us can run guest posts, and we would be happy to consider your contribution. (Here is the posting schedule for the series, with each date corresponding to a separate section of the two volume anthology.) All posts in the series, whether written by our regular bloggers or by guests, will be tagged “Hollinger and Capper,” so that clicking on that tag will pull up the whole discussion.

In the meantime, we can have a conversation via comments on this post. I would love to hear your thoughts.

Editorial note (added April 8, 2018): The first section of Hollinger and Capper’s anthology is entitled “The Puritan Vision Altered” and includes the following readings:

- John Winthrop, “A Modell of Christian Charity” (1630)

- John Cotton, selection from A Treatise of the covenant of Grace (1636)

- Anne Hutchinson [sic], “The Examination of Mrs. Anne Hutchinson at the Court at Newtown” (1637)

- Roger Williams, The Bloody Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience (1644)

- Cotton Mather, selection from Bonifacius (1710)

- Charles Chauncy, Enthusiasm Described and Caution’d Against (1742)

- Jonathan Edwards, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” (1741) and selection from A Treatise Concerning the Religious Affections (1746)

________

*In Envisioning America: English Plans for the Colonization of North America 1580-1640, A Brief History with Documents, 2ndedition (Bedford/St. Martin, 2017), edited by Peter C. Mancall.

**Envisioning America

, pp. 131-137.

15 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Gah! Committed a mortal sin for historians and left out a reference. I have added it above at the sign of the double asterisk.

Such a great question re: Hollinger/Capper. I used Bartolome de las Casas (and The Name of War) last semester to raise the possibility of “the construction and maintenance of white supremacy” as a/the narrative of American intellectual history. Even using the texts Hollinger and Capper selected to trace the accommodation of Protestant Christianity to the Enlightenment, there’s plenty to discuss when you also look for white supremacy.

That’s a fascinating choice of texts and a really interesting approach. Generally, I think it’s promising to envision “American intellectual history” hemispherically before narrowing our focus to “U.S. intellectual history.” There was a fully century of colonizing and colonial narratives circulating throughout Europe before the attempt of settlement at Roanoke — those narratives in translation, as well as “the Columbian exchange,” shaped English ideas and expectations of what a settlement in “the Americas” would mean long before one was attempted. At the very least, Thomas Hariot’s travelogue about Virginia seems like a useful place to start if we don’t want to consider Spanish or French texts in the original or in translation.

But if U.S. intellectual history is taking a more intentional hemispheric turn as a field, I am here for it! Let’s help it turn.

Winthrop’s “That which lies common & hath never been replenished or subdued is free to any that will possesse and improve it…” basically anticipates by 60 years Locke’s argument in the Second Treatise of Government (1689), something I confirmed by a glance at the online Stanford Ency. of Philosophy entry on Locke’s political philosophy (skimmed the section of that entry on ‘property’ until I got to a paragraph about Locke and the American colonies).

I wonder whether Winthrop bothered to find some Biblical (maybe Old Testament?) warrant or support for the view that land that had never been cultivated or “subdued” or “improved” was free for the taking, even if, say, someone else routinely hunted on it. (Possibly a v. silly question, I don’t know, but that’s one thing that comment sections are for….)

Louis, the editor of the Bedford/St. Martin’s edition where I encountered this text offered the following parenthetical note in the middle of Winthrop’s answer to “Objection 1”: [Winthrop goes on to prove a lengthy biblical justification for the Puritans’ right to the land.–ED.]

So the short answer is yes, Winthrop used the Bible to somehow back up his claims.

Thanks

De nada. BTW, I have a typo in the comment above (of course): should read “Winthrop goes on to provide…”

My forthcoming book on liberation theology is all about taking the hemispheric turn by looking at the connections between Latin America, black and feminist liberation theology that has a long history. When I taught the survey course in graduate school, I started with native American cosmology, rich in ideas for intellectual historians to explore. That cosmology was key in why native peoples had such difficulty in their encounter with Europeans, first being the Spanish. Ideas about communal lands, kinship, and relationship to nature were significantly different from the Europeans. I think those ideas combined with hispanic sources are still running through many communities within the US and represent a counter-narrative and politic.

Many do not know that Santa Fe, NM was founded in 1605, right before Jamestown, so maybe the ideas from Spanish colonial history needs to be a greater part of the story of these United States. What we need is a more “cosmopolitan,” in the best sense of the term, intellectual history of the U.S. We have not begun to dig into those sources. Raúl Coronado’s The World Not to Come: A History of Latino Writing and Print Culture does a magnificent job and we need more of it. We had a roundtable on this book on this blog, here is the link https://s-usih.org/2015/05/introduction-for-the-round-table-on-coronados-a-world-not-to-come/

Agreed. I teach the encounter between Natives, Europeans, and Africans as a three-way collision of cosmologies (not to mention a collision of physical worlds and embodied lives).

My very favorite class as an English major in undergrad was Native American Poetry (though “poetry” was simply a convenient genre label to get a course like this listed in the catalog at a university that had no Native American studies program). The course was first taught by N. Scott Momaday, and then by the poet Ken Fields after Momaday left Stanford. I still use a lot of the texts from that course in my own teaching (and in my own living). Some of the creation narratives from the Zuni are absolutely amazing (Nepayatumu man is my favorite) and no doubt continue to play a role in shaping the ideas and culture of the desert Southwest. And the stories from the Pacific Northwest collected in Coyote Was Going There always blow me away — “She deceived herself with milt” is brief, but incredible. There’s also an excellent translation of the Popol Vuh — not part of my undergrad syllabus, but something I picked up later — that I’ve used from time to time in classes.

The Bedford / St. Martin’s “Short History with Documents” series includes a volume called The World Turned Upside Down: Indian Voices from Early America. It has some good texts in it, though (as was often the case) many were translated or simply reported at the time by non-native interlocutors. Powhatan’s speech to Captain John Smith is a case in point. It’s early — circa 1609, published in 1612 — but is it really Powhatan’s voice on that page, or even an approximation of it? Hard to say. I might suggest something from that volume as a place to begin “the American intellectual tradition” — maybe the Iroquois creation story, though the transcription date is very late.

It seems to me that what may hamper many Americanists from thinking and working hemispherically is that our field has generally replicated our sad national affliction of not learning languages besides English. No place is more provincial than the center of an empire. But Spanish and French are absolutely indispensable if we’re going to really get a grip on the development of “American” thought from the era of conquest and colonization right up to the present, as I expect your work will show.

My next goal is to learn Portuguese. People have recommended Duolingo — I’m going to give it a try.

languages, languages! I can get through Portuguese since Spanish is my first language. What I want is German. The Germans had world wide intellectual influence. But their language is tough. It played a huge role in 19th century US because so many Americans went to Germany for their higher education in philosophy and theology. I think that graduate programs use to require two languages besides English. That would surely make the numbers of Ph.D.s awarded lower. You might know about that LD. Not knowing other languages definitely ties one’s hands (mind) in the range of study topics.

Patient readers, I have added an editorial note to the bottom of this post listing all the readings included in this section of the Hollinger and Capper anthology. I will include such a list in all my future posts in this series. My apologies for the omission.

I always begin colonial and first half of constitutional with continental scope, Native Americans and Spanish colonization, but never for first half of intellectual. How embarrassing! That’s changing. One text that might set up Hariot and Hakluyt nicely would be Vitoria’s De Indis, and that has a long life in political thought and international law so it would set up an imperial and continental focus from the beginning well. Great post.

This is a great question, and I look forward to following this series as it develops!

I also like the choice of either Bartolomé de las Casas or Hakluyt, but Ibram Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning also makes me wonder about using one of those early European texts justifying the slave trade, such as Gomes Eanes de Zurara’s The Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea. I’ve also taught Cabeza de Vaca’s account of his travels in a course on the history of the American West, and I thought that worked very well as a place to begin talking about European ideas about race, religion, and wealth.

But a part of me also would want to begin with John Donne’s Elegy XIX: To His Mistress Going to Bed, with its famous lines

License my roving hands, and let them go

Behind before, above, between, below.

Oh my America, my new found land,

My kingdom, safeliest when with one man manned,

My mine of precious stones, my Empery,

How blessed am I in this discovering thee.

To enter in these bonds is to be free,

Then where my hand is set my seal shall be.

The poem postdates most of those works mentioned above, but what a way to start a conversation about the European imagination of the American continents! Working through what it means for Donne to use “America” as a metaphor in this way could set the stage for valuable conversations about gender and force or domination as themes in American history.

“my America”

Challenge accepted. I will be incorporating Donne — and perhaps The Tempest? — the next time I teach the first half of the survey. And I think I will counterpose that text with Zuni poetry.

I am flying over the borderlands between Arizona and Utah right now, on my way to the Golden State, which is most deeply home for me, latecomer and interloper that I am.

“Oh, California, I’m going home. Will you take me as I am…?”

Yes. Always.

It’s not quite as on point as the Donne poem, but I’ll throw into the hopper the last stanza of Berkeley’s “Verses on the Prospects of the Arts and Learning in America” (“Westward the course of empire takes its way/ … Time’s noblest offspring is the last”), quoted in (among other places, I’m sure) Pocock’s The Machiavellian Moment. Part of a winding discussion in which Pocock, among other things, connects the apocalyptic-millennial strain to more secular ideas (see pp. 511ff.).

[And I hadn’t realized until a few minutes ago, probably b/c I’d never thought about it, that Berkeley CA is named after that Berkeley, who’s better known I think as a philosopher than as a poet.]