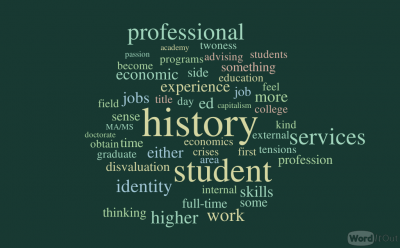

My first thought for a title on this reflection was “identity economics.” I wanted the title to convey something about the interplay of the history profession’s economic structure and the way I, and maybe some circle of we, identify as historians. But then I saw that there is a technical area of economics, titled “identity economics” and made concrete in a book of the same title by George Akerlof and Rachel Kranton. Since I did not intend to engage their work, I reworked my title into something both more awkward and specific.

My first thought for a title on this reflection was “identity economics.” I wanted the title to convey something about the interplay of the history profession’s economic structure and the way I, and maybe some circle of we, identify as historians. But then I saw that there is a technical area of economics, titled “identity economics” and made concrete in a book of the same title by George Akerlof and Rachel Kranton. Since I did not intend to engage their work, I reworked my title into something both more awkward and specific.

In the past month I have been thinking a lot about my history credentials and training, and how both play on my sense of what I deserve as an employed person in the U.S. economy. The occasion for my thinking is going from over-employed (my general state) to under-employed. This change occurred when I lost my full-time day job at the end of March. In our professional parlance, I’m now sort of “between jobs.” This designation minimizes the irritation and pain of losing my day job, but it always conveys two truths. First, I always have some low-level employment ongoing, courtesy of the fact that I like to teach on the side. Second, I’m job hunting and I will do something full-time, during the day, eventually.

The reason I am hopeful that something new will turn up is that my economic well-being does not depend on the history profession. Shortly after I began my graduate work in the field, I acquired a graduate assistantship in student services. For three years I helped students navigate the “dean’s appeal” process in Loyola’s former Mundelein College. I helped them to understand the appeals process, to think about evidence and narratives, and to write good appeal letters. I also had to convey decisions, sometimes adverse, after. As time progressed and our college became short-handed, I was also drafted into student advising (e.g., course selection, degree audits, and general counseling).

This work meant that when I finished my history doctorate in 2006, my first full-time position was in student advising. That came even though I had obtained extensive adjuncting experience in the Chicago area from 2002 to 2006. Since 2006, I have worked four years in history and eight in student services. But, on the latter, I often taught history courses on the side, to undergraduates, graduate students, and adult learners.

In short, and with apologies to W.E.B. Du Bois, I suffer from a kind of professional “twoness” or double consciousness. I feel a kind of economic oppression and, at times, a kind of professional disvaluation in my two chosen fields. The source of my twoness is not race, or course, but rather from capitalism in the history profession and a progressing hyper-professionalization in student services.

On history, the disvaluation comes from the fact that the field is generally not valued in American society at large. The churn of creative destruction, inherent in capitalism, looks not backwards but forwards. But the disvaluation also comes, for me, from the fact that, over time, experience in student services has become somewhat less valued in an age where the higher education credential (MA or MS) has become more of a passport into staff jobs. Historical thinking, inclusive of evidence selection and emphasis in narrative instruction, as well as instructional skills, translate to the academic side of student services. No doubt. But historians are not taught about budgets, student advising, law and ethics in higher ed, higher ed leadership, or policy. I happened to study the history of higher education for my own doctorate, but few history PhDs do that. Most enter the academy and profession with only a passing sense of its foundations.

Underscoring those other relevant topics explains why not every historian succeeds as department chair or moves up into a dean position. You have to both want those skills and obtain an avenue for acquisition. I have done this in student services, by luck and pluck. It has taken years of on-the-job experience. Nobody offered dual history/higher ed programs when I entered the academy in the late 1990s. Plus, meeting the requirements for a PhD/MA or MS, or an MA/MS in history/higher ed, takes a lot of time and money. How can they be integrated while meeting accreditation requirements for a degree with both programs?

My sense of twoness and disvaluation matters, I think, in a professional universe where “alt-ac” has become a buzzword, or signifier, for transferable skills. How do history programs teach advanced historical thinking and critical social science skills, with the required depth, and then expect to send graduates to non-history positions without also planting the seeds for a professional identity crises, or at least identity tensions, either external or internal? By external I mean that it is possible that hiring committees in either history or administrative jobs might not appreciate the “lack” of full-blown devotion in relation to other candidates. Your dual track might seem like a lack of commitment or passion to either field.

On internal professional tensions, I can speak from experience. Even now, as I type these words in my “between jobs” status, I feel the pull of both professions. I could do either full-time. My credentials and work experience in history (e.g. publications and teaching time) make me a strong candidate for assistant (or associate) professorships. And I am committed to that work. But we all know those jobs are few, and becoming more rare. Obtaining them requires a convergence of circumstances–sometimes called luck. On the student services side, my experiences more than total the knowledge learned in an MA/MS higher ed program. As a first-generation college student who almost failed out, but then managed to earn a PhD, I am drawn strongly to at-risk, underprivileged students. I long to advise and mentor them—to help them obtain their higher education dreams. I want them both educated and credentialed. They deserve all the cultural, social, and economic trappings of “the middle class,” at least. So I have a passion for student services.

For me this is less an identity crises than a professional tension. I feel tugs from both sides. I have experienced both failure and success in both venues. My future will be dictated by the circumstances of the moment.

I suppose this reflection is both a success story and a cautionary tale. You can foster skills and experience in two or more fields. The economic structure of the history profession almost demands this. The state of “the market” in history, when you enter it, will dictate your outcome. Or you can obtain work in your “alternate” area, as circumstances dictate. But you might never escape some inherent tensions. And those pushes and pulls might occasionally boil over into a professional crises, precipitated by either external or internal factors. A job loss may be one of those factors. Then the twoness you’ve obtained, and perhaps buried for a while, might resurface—cutting into your sense of unified identity. Or it might slice through barriers, enabling some future success. – TL

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Join the club. Very few people stay in one career track all of their lives. It’s becoming more rare which means most have to reinvent themselves at least every decade. Or juggle two careers like you have. I know others successful at two simultaneous careers. It’s exhausting changing gears. I had done it four times moving from one profession to another from scratch. Started out as a CPA, to non-profit director, author/speaker, to now here I am a historian on my own. The toughest economic gig thus far. These were not smooth transitions with lots of inbetweenness, if that’s a word. Every time, it’s been painful. One’s identity gets caught up in a situation only to have to discarded for a new one. Impossible to carry seniority/status earned in one to another. Nobody cares. What that means for me is that most of life, I feel like a freshman and in between this and that. So what is my “economic identity”, fluid, how about “professional non-conforming”? Best of luck to you.

Thanks for the comment, Lilian. History was my second career, but, as per above, that was quickly combined with student services. Hence, my dual priority since the year 2000—when I obtained that graduate assistantship—has been both history and student services. The percentages have shifted with various jobs since 2006. And it just so happens that, at this time and in this change, I’m sensing another shift possibility. But it would be great (right?!) if people felt more secure in the percentages and could map out career plans accordingly.

Another point of the post above is just to say that “alt-ac” creates some layers of professional security, but it also might also foster some identity insecurities. The tensions and pressures between our various selves will rise and fall according to circumstances that are outside our control. – TL

Great essay. I’m wondering if you found yourself thinking about this tension during your grad student days. Did you have a sense of this alt-ac twoness while you were working in student service/advising and writing your dissertation?