On a prompt from a friend, I’ve been reading a little about pseudo-intellectual Jordan Peterson. In a New York Review of Books piece reviewing Peterson’s new book, 12 Rules for Life, I ran across this passage (bolds mine):

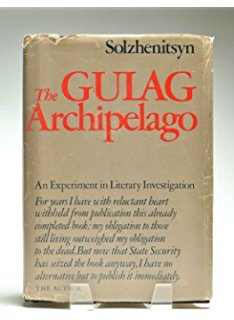

Peterson himself credits his intellectual awakening to the Cold War, when he began to ponder deeply such “evils associated with belief” as Hitler, Stalin, and Mao, and became a close reader of Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago [published in English in 1974]. This is a common intellectual trajectory among Western right-wingers who swear by Solzhenitsyn and tend to imply that belief in egalitarianism leads straight to the guillotine or the Gulag. A recent example is the English polemicist Douglas Murray who deplores the attraction of the young to Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren and wishes that the idea of equality was “tainted by an ideological ordure equivalent to that heaped on the concept of borders.” … Solzhenitsyn, Peterson’s revered mentor, was a zealous Russian expansionist, who denounced Ukraine’s independence and hailed Vladimir Putin as the right man to lead Russia’s overdue regeneration.

I was caught off-guard by the Solzhenitsyn reference. That said, my acquaintance with his work is thin, mostly to due to a few friends who were fans. One old friend was a huge Solzhenitsyn admirer. In politics, she was a right-leaning centrist, mostly a consequence of her evangelical Christianity. But she also held a number of left-leaning views, particularly in relation to the LGBTQ community. As an aside, she was also a Henry James super-fan. I never knew exactly what to make of the two allegiances, considered together. But I never forgot her curious attachment to Solzhenitsyn.

But, on Peterson and his ilk, what is the American right, and alt-right, getting out of Solzhenitsyn? Why bother? How far back does this go? When did it all begin?

A 2008 Guardian article, written a few days after Solzhenitsyn’s death, provides a few clues. First, it appears right-wingers may appreciate his trenchant critiques of Bolshevism, Marx, and Engels. Solzhenitsyn criticized how an atheist Marxism and Bolshevism suppressed the Russian Orthodox Church, which Solzhenitsyn defended and admired. That Church, he believed, was the fount of Russia’s traditions and culture.

Matthew Heimbach, undated.

This is, I think, key. We know that some American white nationalists and alt-right figures, such as Matthew Heimbach (of the Traditionalist Workers Party, right), admire the revived Russian nationalism and traditionalism that centers on Russia’s seeming racial homogeneity. The view of Russia as a “Motherland” friendly to white supremacy and anti-Semitism appeals to segments of the alt-right. With his admiration of the cultural effects of the Russian Orthodox Church, Solzhenitsyn also called for a larger Slavic state (pan-Slavism) that would include Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus—a call that Putin no doubt has found advantageous. In this coordinated political and religious ideology, Putin is seen as a “lion of Christianity.” To cement the connection he has fostered a close relationship with the Russian Orthodox Church. Heimbach, to live out this connection in America, was baptized into the Russian Orthodox Church. Putin, Heimbach believes, fights for “faith, family, and folk.” This view has also been imported to America through the World Congress of Families, which promotes right-wing Christianity. The WCF has advocated for the U.S. to adopt something like Russia’s 2013 anti-LGBT law. To the American right, then, Solzhenitsyn’s call for Russia to return to its Orthodox roots coincides with the right’s view that America return to to traditional Christianity and cultural mores.

Solzhenitsyn also evolved into a critic of Western individualism, materialism, and liberalism. He did so after having witnessed the disruptive effects that accompanied the reintroduction of capitalism into Russia. This aspect of his thought was cemented, for Americans, in a June 1978 commencement address at Harvard (video and transcript at this link). Here are some excerpts (bolds mine—pardon the length):

If I were today addressing an audience in my country, examining the overall pattern of the world’s rifts, I would have concentrated on the East’s calamities. But since my forced exile in the West has now lasted four years and since my audience is a Western one, I think it may be of greater interest to concentrate on certain aspects of the West, in our days, such as I see them.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, circa 1974, courtesy of Wikipedia

A decline in courage may be the most striking feature which an outside observer notices in the West in our days. The Western world has lost its civil courage, both as a whole and separately, in each country, each government, each political party, and, of course, in the United Nations. Such a decline in courage is particularly noticeable among the ruling groups and the intellectual elite, causing an impression of loss of courage by the entire society. Of course, there are many courageous individuals, but they have no determining influence on public life. …

The defense of individual rights has reached such extremes as to make society as a whole defenseless against certain individuals. It’s time, in the West — It is time, in the West, to defend not so much human rights as human obligations.

Destructive and irresponsible freedom has been granted boundless space. Society appears to have little defense against the abyss of human decadence, such as, for example, misuse of liberty for moral violence against young people, such as motion pictures full of pornography, crime, and horror. ..

The press too, of course, enjoys the widest freedom. (I shall be using the word press to include all media.) But what sort of use does it make of this freedom?

Here again, the main concern is not to infringe the letter of the law. There is no true moral responsibility for deformation or disproportion. What sort of responsibility does a journalist or a newspaper have to his readers, or to his history — or to history? If they have misled public opinion or the government by inaccurate information or wrong conclusions, do we know of any cases of public recognition and rectification of such mistakes by the same journalist or the same newspaper? It hardly ever happens because it would damage sales. A nation may be the victim of such a mistake, but the journalist usually always gets away with it. One may — One may safely assume that he will start writing the opposite with renewed self-assurance. … Hastiness and superficiality are the psychic disease of the 20th century and more than anywhere else this disease is reflected in the press. …

The American Intelligentsia lost its nerve and as a consequence thereof danger has come much closer to the United States. But there is no awareness of this. Your shortsighted politicians who signed the hasty Vietnam capitulation seemingly gave America a carefree breathing pause; however, a hundredfold Vietnam now looms over you. That small Vietnam had been a warning and an occasion to mobilize the nation’s courage. But if a full-fledged America suffered a real defeat from a small communist half-country, how can the West hope to stand firm in the future?

As humanism in its development became more and more materialistic, it made itself increasingly accessible to speculation and manipulation by socialism and then by communism. So that Karl Marx was able to say that “communism is naturalized humanism.” … One does see the same stones in the foundations of a despiritualized humanism and of any type of socialism: endless materialism; freedom from religion and religious responsibility, which under communist regimes reach the stage of anti-religious dictatorships; concentration on social structures with a seemingly scientific approach.

Even a mere cursory review of the highlighted passages above reveals what might resonate with the American right: criticism of weak politicians, disdain for hyper-individualism, concern for morality, contempt for the media, critique of a general loss of nerve in international affairs, concern for the decline from humanism to materialism, anti-Marxism, etc.

The Harvard address may indeed be the point after which Solzhenitsyn found friends on the American right. This 2014 article by Lee Congdon in The American Conservative

—which is a review of Daniel Mahoney’s The Other Solzhenitsyn— points to 1978 as the turning point. Mahoney’s work argues that Solzhenitsyn was a misunderstood patriot who loved his country—not an anti-Semite, a nationalist, an imperialist, or an authoritarian. Even so, Congdon, in contradistinction to Mahoney, does not dare to argue for Solzhenitsyn as a democrat. This is a point to be noted, perhaps, in relation to the alt-right’s admiration for Solzhenitsyn. They can use Mahoney’s defense of Solzhenitsyn as a democrat to insulate themselves from criticisms about the authoritarianism inherent in their actions and tactics.

Solzhenitsyn with Putin, undated.

To Solzhenitsyn, Putin’s emergence offered a remedy to these diseases. Putin was an alternative—as were the communal aspects of Russian Orthodoxy. Meanwhile, Solzhenitsyn’s unassailable anti-Communist and anti-Stalinist credentials insulate him from criticism that his work somehow denigrates liberty. Even if pan-Slavism and pro-Putinism imply the restriction of freedom, the invocation of Solzhenitsyn can cloak one’s authoritarianism in a widely respected author and his great works. Solzhenitsyn’s courage in the face of Soviet repression can never be denied.

If 1978 didn’t convince American conservatives that they’d found a friend in Solzhenitsyn, they had a confirmation of applicability in 1980 from one of the their great intellectuals. In that year Russell Kirk positively reviewed a new book by Edward Ericson, titled Solzhenitsyn: The Moral Vision (Eerdmans). Ericson recounted that review and his memories of it in a 2012 piece at The Imaginative Conservative. Here’s a sample (bolds mine):

In that aforementioned review, Kirk writes, “The purpose or end of humane letters is ethical: a point forgotten by most writers and reviewers nowadays.” And he specifies that “Solzhenitsyn’s great concern is the moral state, rather than the political state.” Then he aligns Solzhenitsyn with T. S. Eliot: “Like Eliot, Solzhenitsyn sets his face against both the dread tyranny of Communism and the ‘Western’ infatuation with sensual satisfactions, and trifling material possessions.” This leads to Kirk’s next observation: that “Solzhenitsyn’s moral vision is what Eliot called the ‘high dream’—the vision of Dante, the Christian extrasensory perception of true reality. Even more than Dante, Solzhenitsyn passed through the Inferno, and was purged of dross.”

And here’s this on conservatism and ideology—delivered without irony (bolds mine):

The subject about which knowing my Kirk best prepared me to appreciate Solzhenitsyn was the subject of ideology. I recall an argument that raged among conservatives at one long-ago time about whether conservatism was an ideology or not. Kirk said not. As I followed the argument among my betters, with each side populated by writers whose ideas had helped me, I concluded that Kirk was right. Although time has dimmed my memory of the details of the argument because I came to a settled conviction on the matter, I agree with him that conservatism, far from being an ideology, is a negation of ideology. Then I came to Solzhenitsyn, and one confirmation of our consanguinity was his rejection of ideology—not just Marxist ideology but ideology per se. Both Kirk and Solzhenitsyn saw ideology as rooted in utopian thinking and avoided that loose usage common today that employs the term ideology to refer to any well-developed perspective, or world view.

On this Ericson and Kirk obviously differ with the alt-right, Heimbach, Putin, and Peterson. The latter use Solzhenitsyn’s pan-Slavism and Russian Orthodoxy to buttress their political ideology of state-sponsored traditionalism, nationalism, and white supremacy. Solzhenitsyn is used, then, as some Marxists, or rather Stalinists, used Marx.

The Ericson piece draws further parallels between Kirk and Solzhenitsyn, most of which given by Kirk in his 1993 book, The Politics of Prudence. The idea of the “moral imagination” is an important theme in the rest of Ericson’s reflection. But how do we square that with what we know about the alt-right’s white supremacy and Putin’s authoritarianism?

Returning to Jordan Peterson, what do we make of things, in 2018, when an alt-right, neo-fascist finds inspiration in one of great books of anti-communist liberalism? Indeed, on the latter, David Remnick said the following, in 2003, about The Gulag Archipelag

o: “It is impossible to name a book that had a greater effect on the political and moral consciousness of the late twentieth-century.” He also called it a “masterwork.”

Given the praise from Remnick and Ericson, it would seem that today’s alt-right pseudo-intellectuals (or “intellectual entrepreneurs,” to Pankaj Mishra) are engaging in a little cafeteria Solzhenitsynism? Alt-right ideologues have to pick-and-choose, at least a bit, to find a political hero in Solzhenitsyn. Or maybe they read a “late Solzhenitsyn” and ignore his more nuanced early and middle career?

In any case, the answer to the question of when Solzhenitsyn became important to the American right, generally, was 1978. The story above explains why. But since Solzhenitsyn himself cannot object to the associations being made in his name, we’ll never know whether he approves, or disapproves, of the alt-right appropriation. It’ll be interesting to see how much longer this continues. – TL

11 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Recently I read an article by Timothy Snyder, “God is a Russian,” in NYRB 4.5.18, about Ivan Ilyin, an early 20th c Russian philosopher who apparently had some influence on Solzhenitsyn and, more recently, Putin. I think you’ll find it illuminating.

Thanks Bill! Apparently several of us are trying to understand this connection (or series of connections). – TL

For those also interested, here is the direct link.

Tim, this was a fascinating read. I have seen some overlap between dalliance w/ the Russian Orthodox Church and defense of “the canon” in my own research (teaser!).

What’s also quite interesting to me is the missiological shift in some evangelical / fundamentalist / Dispensationalist / Baptist (or anabaptist) circles (or the set of the Venn overlap of all four). When Billy Graham first went to Russia in the early 80s to hold a crusade, there was a great deal of excitement among that set, and a great deal of scorn for the Russian Orthodox church.

The sense was that as the officially recognized Church of an officially atheistic state, the Russian Orthodox church was spiritually dead inside and Russian Orthodox Christians were not really Christians because they had never heard the gospel. This was the judgment of many a mega-church pastor (including my parents’ pastor) who visited either the Soviet Union during Glasnost or Russia after the collapse of the USSR, and I would bet you could find this sentiment in missionary publications, newsletters, reports, etc.

After the fall of Soviet Union and the (purported) end of the Cold War, you begin to see a shift in missiological teaching at places like Fuller Theological Seminary and even Dallas Theological Seminary. It doesn’t happen all at once, but there’s a significant ratcheting down of the idea that “the Spirit” (meaning the Holy Spirit) was nowhere to be found in state-sanctioned churches and an embrace of the idea that the job of the missionary (or stateside evangelist) was not to decide where the Spirit could and couldn’t work but to follow the Spirit’s leading and go where the action is. So, rather than sending missionaries to “save” Orthodox Christians or Catholic Christians from the error of their ways when it comes to ecclesiology and soteriology, the idea was to send missionaries to partner with (trinitarian) Christian communities of any kind.

This shift reflects the rising prestige of Pentecostal theology. But it also reflects the end of the Cold War. I think recent polling and election returns have demonstrated, as perhaps nothing else could, that what holds self-identified “evangelicals” together is not a set of theological beliefs but a sense of ethno-nationalist identity. With the triumph of America in the Cold War, the state-sanctioned Russian Orthodox Church could be viewed not as a counterfeit of the “true” church (composed only of those who “have a personal relationship with Jesus Christ”), but as another means by which the triumph could be extended.

And this embrace of — or at least willingness to respect — the Russian Orthodox Church is happening at the same time that missiological instruction in seminaries is eschewing nationalist / Western supremacist overtones and becoming more respectful towards other cultures. Missiology as a theological discipline undergoes globalization, and the ethnonationalists, East and West, find each other in the backwash of that wave.

I confess to not having given much thought to the history and present study of missiology, esp. in terms of Protestantism generally. So your comments are obviously welcome. I had friends in college—members of Campus Crusade for Christ—who visited and were missionaries in Hungary and other Slavic countries. But none ever “crusaded” in Russia.

In relation to Catholic history and missiology, I’m now wanting to reframe those Cold War actions and interactions regarding the Papacy, especially John Paul II. I need to read some articles, for starters, on how JPII and other Vatican officials interacted “ecumenically” with the Russian Orthodox Church. I also need to read some work on the Catholic Church since the mid-1970s and Solzhenitsyn. I expect this newly emergent connection to the alt-right will color my view of those writings and interactions. – TL

LD – I wonder how they purport to reconcile “ethno-nationalism,” whether of the US or the Russian variety, with what seems here the hint of a globalizing perspective. It’s sweet to think the one might stand for or into the other, perhaps through the device of “the” individual’s personal relationship with Christ, but doesn’t that typically manifest as a sort of trinity of the cross, the flag and me; and don’t most real-world “beloved communities” express themselves in nationalist terms? Just asking.

“America for the Evangelicals, Russia for the Russian Orthodox” — that’s one way to reconcile ethnonationalism with a global solidarity among coreligionists, broadly construed.

Thanks for this post and the research that went into it.

Herewith some somewhat off-the-cuff views of Solzhenitsyn.

1) Have read a couple of his novels: The First Circle, which I don’t remember at all well, because it was very long ago, but I was impressed by it, and August 1914, considerably less successful as a novel and a part of a rather bloated historical trilogy as I recall, one colored to its detriment by his politics at that point, but there are some good passages in it just from the standpoint of the writing. Clearly a talented novelist. Displayed great personal courage early on when sent to a prison camp by the regime. That’s basically the only favorable things I have to say about him.

2) His politics, esp. in the later part of his life, were utterly, irredeemably terrible. Anti-democratic, ethno-nationalist, basically opposed to personal choice and liberty if it conflicted with his rigid notions of “morality” (one can see this in the ’78 commencement speech). Whatever moral authority S. might have had as a survivor of and chronicler of the Gulag was compromised by the ’78 speech and its sequels, as can be seen just from the excerpts given in the post. For example, he clearly knew little to nothing about the Vietnam War, but that didn’t prevent him from pontificating about it and other matters.

3) He lived in relative seclusion in Vermont for years after defecting to the West, not bothering to really acquaint himself much with the country in which he was living but offering periodic (though fewer and fewer, I think) denunciations of materialism, laxity in morals, etc.

4) I’m really not sure what the alt-Right today is getting out of S. as a practical matter, b/c I think, to be blunt, that the relative thinness of historical memory in much of the Western public means that a great many people barely remember who S. is, and, if they do, they don’t really give a **** about him. But I’ll tell you who, long before the alt-Right existed, very much liked the ’78 commencement speech, and that was much of the nascent neoconservative movement. Recall, for example, that the year following S’s ’78 speech saw the appearance of Jeanne Kirkpatrick’s notorious Commentary article “Dictatorships and Double Standards.” Recall that the neocon Committee on the Present Danger, set up to hype the continuing Soviet threat, was formed around that time. The stuff in the ’78 speech about the West’s loss of nerve and courage, etc. — the neocons just lapped that up.

Sorry to ramble; I’m done.

“Returning to Jordan Peterson, what do we make of things, in 2018, when an alt-right, neo-fascist finds inspiration in one of great books of anti-communist liberalism?” Since Peterson is quite clearly neither of the alt-right nor a neo-fascist, as any seriously honest investigation of his work would show (Mishra’s hatchet job in the NYRB certainly isn’t), the claim to the contrary cannot help but call the author’s judgment seriously into question.

Solzhenitsyn’s enduring popularity among right-wingers in Germany was my main motivation to study his Western reception in my PhD (“Alexander Solzhenitsyn: Cold War Icon, Gulag Author, Russian Nationalist?” ibidem /Columbia Universtiy Press, 2014). It turns out that people on the right in the West are not “misreading” the author, there are plenty of examples of nationalism, anti-Semitism, anti-feminism, revisionism, etc. in Solzhenitsyn’s work. To be sure, many of his readers like him for his anti-communism, but that does not erase these other aspects of his work. Unfortunately, the prestige of the Nobel Prize and his status as “moral icon” is used by right-wingers to give credibility to the revisionist views they share with Solzhenitsyn.

Interesting — thanks for posting this.