To start off our series on Martin Luther King, Jr. and his intellectual legacy, I want to examine a sermon he gave at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in 1957. This speech, titled “The Birth of a New Nation,” is an intriguing look at how King and other leaders of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement of the late 1950s viewed the independence of Ghana and other African states as important to the global cause of freedom. King and other leaders often linked together independence movements in Africa and Asia to the struggle for civil rights at home. We should understand how this took place in a Cold War context—thus, some of the radicalism of explicitly anti-colonial campaigns led by African American radicals in the United States had lost considerable steam due to Cold War red-baiting by the 1950s.[1] It’s important to couch the speech in that context—along with Black America’s overwhelming interest in African, and world, affairs.

King’s speech is intriguing partly for its use of history. Make no mistake: often when Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke, he used every opportunity to educate his audience about American and world history. This will be a theme that will be picked up on with this weekly series. In “The Birth of a New Nation,” King mentioned the history of exploitation by outside powers of Africans, pointing out the entry of the Portuguese and then the British into the politics and internal affairs of the Gold Coast, the name for the West African region before it became Ghana. While Malcolm X often made these same links in his speeches, it seems King’s speeches and sermons—at least in a public memory context—are usually stripped of these links until his anti-war activism.

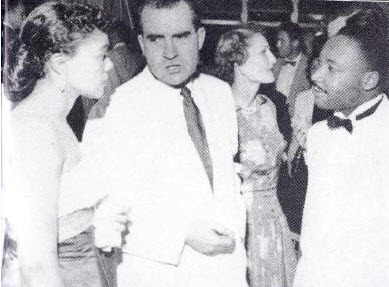

The relationship between King and Kwame Nkrumah, the central figure in Ghana’s independence, is also a critical part of this speech. It’s a reminder of the links King had with many figures across the African diaspora. Look at guests from U.S. there with King—Ralph Bunche formerly of the United Nations, longtime activist and socialist A. Philip Randolph, Howard University President Mordecai Johnson (the first African American president of the HBCU Howard), and Vice President Richard Nixon were on hand to see the independence ceremonies. King speaks highly of Nkrumah’s leadership, finding it to be an inspiring story for any freedom-loving people.

This photograph of the Kings with then-Vice President Richard Nixon was taken at Ghana’s Independence Day ceremonies.

King’s speech also includes a strong condemnation of British imperialism in Africa and elsewhere. Visiting London on the way back to the United States, the Kings had lunch with C.L.R. James—again, reminding us of the many links between intellectuals within the Black Diaspora. During his sermon, King condemned both the British government and the Church of England, whom he charges with the crime of sanctioning the international wrongs perpetrated by the British. His recollection of Winston Churchill’s immortal quote—“I did not become his Majesty’s First Minister to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire”—is used here to frame the joy of Ghana’s independence celebration with the understanding that a new day was on the horizon for the entire world. It was an end of the age of empire, and the start of dozens of new and independent nations. His criticism of Britain’s role in the Suez Canal Crisis of 1956 is another example of how King is looking at world affairs in the late 1950s.

Finally, King condemns Britain by using a phrase that is likely familiar to people who know King’s speeches from 1967-68. He speaks of God “break(ing) the backbone of your power” if Britain—and other colonizing powers—continue to brutally subjugate millions around the world. This line is a take off from Leviticus 26:19, which goes: “And I will break the pride of your power, and I will make your heaven as iron, and your earth as brass.” While Leviticus 26 is a warning of what happens to nations when they disobey God, the line is well known today for how King invokes it to condemn American involvement in Vietnam in the 1960s. Most notably, his “It’s a Dark Day in Our Nation” given on April 30, 1967 invokes the “break the backbone of your power” line. There, King relates American complicity in crimes in Southeast Asia to the nation’s own moral failings. In a sense, by reading King’s words on Ghana’s independence celebration, you can see how his thinking about American foreign policy is already developing.

Martin Luther King, Jr. refused to see colonialism abroad as separate from the racism issue at home. He argued that “there is no basic difference between colonialism and racial segregation.”[2] It is a disservice to King to merely see him making these links in the last eighteen months of his life. Nonetheless, the way King talks about Ghana’s independence is a signature moment in his public career of thinking deeply about local phases of global problems. While the African American left kept alive dialogue about the links between African Americans and Africa in magazines such as Freedomways and Liberator in the early 1960s, King was doing the same. His critiques also foreshadowed his own critiques of American imperialism. He was already willing, in the late 1950s, to criticize Cold War liberalism for its failures, both at home and abroad, to address issues of poverty, racism, and militarism.[3]

[1] Penny Von Eschen, Race Against Empire: Black Americans and Anticolonialism, 1937-1957 in particular emphasizes this point.

[2] Thomas J. Jackson, From Civil Rights to Human Rights.

(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), p. 81.

[3] Jackson, 82-84.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Robert, thank you so much for this rich and illuminating post. I started teaching on the Cold War today, and touched briefly on the Cold War context for civil rights struggles at home and liberation struggles abroad, though I’ll cover that more in subsequent lectures. I’ll be glad to assign my students to read this post, and others in the series.

Thanks for this. Am looking forward to the other posts in the series.

Robert: Thanks for this! I’ve leaving this comment, in part, to let you know that I’m following your series. Even though I originally wanted this blog to work toward a full understanding of ideas and intellectuals in our domestic setting, I *love* seeing posts with international connections. That larger context is so often crucial to understanding how things play out domestically with individuals, groups, and institutions. – TL