Editor's Note

We are about the task of defining, defending, and illustrating blackness.

This means that we are about the truth of this world. For we see blackness in America merging with the blackness and the brownness of the Third World and becoming the world. Which is another way of saying that blackness is a truth which stands at the center of the human experience, and that all who reflect the rays of that dazzling darkness reflect a truth which is close to the truth of man. For if truth, as Jean-Paul Sartre noted, is the perspective of the truly disinherited, then the black man is the truth or close to the truth.

–Lerone Bennett, “The Challenge of Blackness,” speech at first national conference, Black Studies Directors, Institute of the Black World, November, 1969.

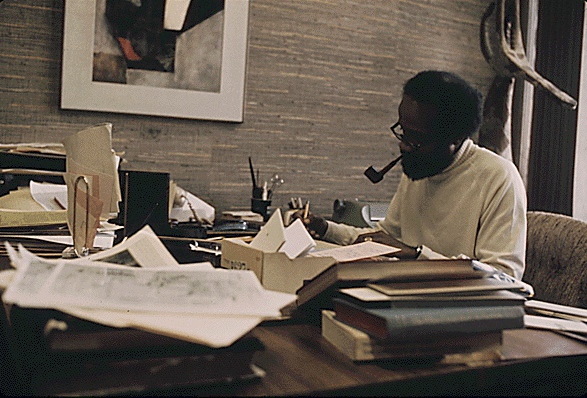

A few weeks ago, I was speaking with a few friends of mine in our history department here at the University of South Carolina. Excitedly talking about our current research, one of them asked me a question about Lerone Bennett, Jr.—knowing that I’d written about him before, she wanted to pick my brain about his writings in relationship to public debates over history, memory, and the creation of knowledge for African Americans. We all marveled at just how prolific Bennett was. We all also recognized that he played an instrumental role in the popularization of African American history in the 1960s and 1970s, continuing in a longer tradition of African American historians who wrote for a black public hungry for knowledge.

When Bennett’s death was announced several days ago, I thought back to that conversation. More than anything I can write here, that conversation was a testament to the legacy of Lerone Bennett. He wrote African American history for the masses—for African Americans, and for anyone else willing to

give a powerfully written, and researched, history often at odds with how mainstream America remembered its past a fair shake. He did the kind of work that most historians say they want to do: for the public, accessible, and necessary

for the public good. Lerone Bennett’s long career is a testament to the kind of history that can make a difference in the public sphere.

Bennett was always writing for an African American audience. This is important to understanding his career. The books he wrote—Before the Mayflower, The Challenge of Blackness, What Manner of Man, and Forced Into Glory, among others—were first and foremost books for the African American public to read, ponder, and debate. Combined, Bennett’s books tell a complicated—but still accessible—history of African American life in North America. In Lerone Bennett’s pageant of African American history, the every day struggle of the average black person is at the heart of his story.

The same was true of his long tenure at Ebony magazine. There, Bennett led the way for African American history’s taking of the center stage in 1960s popular culture. His essays on African American history and life in the United States should be required reading for any African American studies course. More than that, I would go so far as to say they should be required reading in any American history course dealing with the twentieth century. Bennett dared to ask difficult questions of American life; the center of his writings was African America, but his lessons were necessary for America as a whole to understand.

James West’s tribute to Bennett at Black Perspectives is a must-read. His book on Bennett promises to be an essential read as well. But West’s essay is also a necessary read because it captures the scope of Bennett’s writings—from the heights of the Civil Rights Movement and the rise of Black Power in the 1960s, to the struggles to hold onto material and political gains for Black America in the 1980s and 1990s. Bennett was always there for African Americans, ready and willing to ask the hard questions about American life in the modern age.

Lerone Bennett was part of a long tradition of African American scholars as intellectual warriors. I do not say this lightly. From W.E.B. Du Bois and Anna Julia Cooper to Carter G. Woodson to Bennett to scholars like Keisha Blain today, African American scholars in the humanities—among so many disciplines—have had to use their intellect and knowledge in the public sphere on behalf of Black America. Bennett recognized that a clear and unabashed understanding of history was important in the United States, a place where the uncomfortable truths of the past are subsumed by “memory” of an illusory age of glory. To join the battle of ideas is not something all African American scholars, first starting out in graduate school, always seek to do. I know I certainly did not. But the example of Bennett and so many others pushes us on to remind the public of the majesty and tragedy of understanding history.

Lerone Bennett knew that the value of a college education was also something African Americans—indeed, no Americans—could take for granted. In a speech at Benedict College in the 1980s

, Bennett extolled the virtues of a good college education. He said, “You go to college not to learn how to make money, but to learn how to make life, and to learn how to make freedom.” He spoke to an audience of African American students at a Historically Black college in Columbia, South Carolina, an audience that knew all too well the value of education for a historically oppressed group of people.

“Read right, within the context of social forces struggling for dominance, African-American history is a radical reappraisal of a society from the standpoint of the men on the bottom.” Lerone Bennett wrote those words in the introduction to the Ebony Pictorial History of Black America, a three-volume set compiling African American history and images from Ebony magazine’s massive (even in 1970-71, when the series was first published) archive of essays and photographs of African American history. His words still ring true today. The losses of scholarly giants in recent years such as Bennett and Vincent Harding should serve not only as moments to grieve over what we’ve lost, but to celebrate what these and other scholars have given us—and what we as historians should strive to do.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Well done. As someone who is rather inchoate when it comes to the numerous AA-intellectuals that are out there, I appreciated this post. Looks like I need to add Bennett to the bookshelf. Any suggested readings for a newcomer?

Another thought. Re: the excerpt from Bennett, was he implying blackness is a sort of truth in a metaphysical sense or was he merely suggesting that being human with black skin is another facet of what we might call the “human condition” and worthy of studying, understanding, and defining as such?

Wonderful post! Lerone Bennett was an intellectual giant — a brilliant scholar who was also a man of great kindness and elegance. Many of us mourn his passing.