I’m Kinda Like W.E.B. Du Bois

Meets Heavy D and the Boyz

–Tariq “Black Thought” Trotter, “Get Busy” (The Roots album, Rising Down,

2008)

The world of hip hop provides an interesting place to think about the intersection of intellectual history and popular culture. Today I am going to examine this interplay in the realm of African American memory—that place which houses so much of African American reflection on the American past, both the best and the worst of that past. Hip hop provides a rich lens through which to view the past, and more importantly for the purposes of today’s essay, think about how popular culture remembers that past. Hip hop songs, music videos, and the visual culture surrounding album cover art can all provide avenues of discussion of the past.

This is especially vital when thinking about American history since 1968. As I’ve written about before, scholars such as Zandria Robinson have referred to it as a “post-soul” era, a period of history that begins with the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Hip hop as both worthy of study and as a potential source for historians will be integral to getting at the heart of American history in the “post-soul” period. Historians and music journalists began the process of historicizing hip hop years ago. Today I’ll just offer a few examples of what I’m talking about in terms of hip hop and African American memory. More scholars will, I am sure, pick up on this line of reasoning soon—if they have not already started to do so!

From the earliest days of hip hop, the use of history within lyrics was underway. Afrika Bambaatta and the Soulsonic Force’s “Renegades of Funk,” part of the Planet Rock album of 1986, included the lyrics,

Prehistoric ages and the days of ancient Greece

On down through the Middle Ages

When the earth kept going through changes

There’s a business going on, cars continue to change

Nothing stays the same, there were always renegades

Like Chief Sitting Bull, Tom Paine

Like Martin Luther King, Malcom X

They were renegades of the atomic age

So many renegades

In this way Afrika Bambaattaa and company emphasize how they’re renegades of music, in the way these figures were renegades in their own time. It’s especially interesting to see them put together Chief Sitting Bull and Tom Paine with African American leaders King and Malcolm X. Soulsonic Force melds together the civil religious icons of many different facets of American society through this one section of their song. Coming as it did the year of the first celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday as a national holiday, it also serves as a celebration of resisting the status quo in Reagan’s America. It’s also worth noting that if these lyrics seem familiar to you—but you’re not a fan of Afrika Bambaataa—that may be because the song was re-done by Rage Against the Machine, a rock band that is a symbol of 1990s radicalism and proponents of modern leftist agitprop. “Renegades of Funk” acquired a second life in punk rock that allowed the song to live with a new generation of listeners.

Another group of hip hop artists deserving this look is The Roots. Based out of Philadelphia, The Roots are probably best known today as the in-house group performing for Jimmy Fallon’s late night talk show. Before that, though, they enthralled millions of music fans with their unique sound and their socially conscious lyrics. The band was founded and is still led by its two most prominent members: Tariq “Black Thought” Trotter and Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson. The Roots have utilized memory of the African American past in a variety of ways.

1898 Political Cartoon from Wilmington, North Carolina. “Negro Rule.”

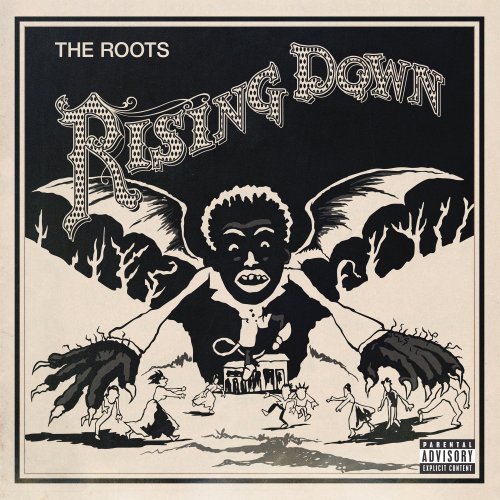

The cover art for their album Rising Down uses the infamous political cartoon that described the rise of African American political power in Wilmington, North Carolina right before the tragic coup of 1898 there. Coming out in 2008, Rising Down was a commentary on America at the end of the George W. Bush years. While many Americans were filled with a sense of hope due to the political rise of Barack Obama, The Roots’ album—definitely one of the best of their long and illustrious careers—reflects a worry about America’s future.

Cover of “Rising Down,” Based off of the infamous political cartoon that helped spark the Wilmington Coup of 1898.

Another artist who appeals to the past in some of his songs is Big K.R.I.T. Real name Justin Scott, Big K.R.I.T. (King Remembered In Time) hails from Meridian, Mississippi, and is part of a long tradition of Southern hip hop reflecting rural sensibilities and worries. He follows performers such as Goodie Mob and Arrested Development in rapping about life for African Americans in the rural South. His debut album, Live From the Underground, was rich with imagery of the rural South. But the song “Praying Man,” a collaboration with B.B. King (Yes, that B.B. King

) featured lyrics about lynching and slavery. They were designed to make the listener think about the long, painful history of being black in America.

These are just three examples of thinking about how hip hop helps to shape American memory of the past. I was tempted to write African American memory, but it’s worth noting just how much crossover appeal many of the biggest hip-hop artists have in modern American music. Kendrick Lamar performed at halftime of this year’s national championship game in college football. Common performed poetry at the White House for President Barack Obama. The lyrics, music videos, and album artwork surrounding hip hop can help us understand how their fans view American history. It is no stretch to say that understanding hip hop helps us to understand modern America—and how modern Americans think about ourselves.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

It’s worth noting that one of the first singles to feature sampling rather than singing for the ‘vocal’ was “Malcolm X–No Sell Out” by Keith Leblanc (1983). I had read the autobiography and was excited to hear this combination of a beat and a chopped up speech. Where did I hear it? Some underground source. But you could buy the single. A whole new type of music coming …

Wow, that’s awesome–and not surprising at all!

Blues relates directly, does it not, to the African American past. Jazz, perhaps likewise, I am working on a history of “The Colored Community” of Sioux Falls and greater South Dakota from 1900 into the 1940’s. And I am not sure how understanding Hip Hop will help me understand that community. Please explain, or am I missing something here. Also, it seems to be that Hip Hop is a kind of artistic vessel into which can be poured a wide range of expressions — expressions which reveal different types of identity (ethnic, culture, religious, gender, etc). Certainly Hip Hop in Malaysia has a different “soul” than that in our country. One example…… https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QA7Zoa3e6Fs

I see hip hop as integral to understanding African American history after 1968, as noted in my piece above. The Blues, certainly, is another wonderful art form that can be used in this same fashion. With your current research topic–which sounds fascinating!–the Blues would certainly be useful. But note that my piece is specifically about the period after 1968.

Robert Thanks for responding. I somehow thought you were going back in time, way back. I myself know little about hip hop except that it seems to have different components (rap, bboy etc.) and that it is not static. As I’ve said, by exposure to hip-hop is through Malaysia and from what I can tell much of Malaysia popular much has hip-hop influences. As I indicated, I am exploring the growth and development of the “Colored Community” of Sioux Falls and greater South Dakota going back to 1900 and it is part of a larger study looking as the growth and development of the other lesser known ethnic communities including Greeks, Italians, Jews, Chinese, and Syrians (both Christian and “Mohammedans”) — there were over 250 Muslims in Sioux Falls in 1915 (many worked on railroad section gangs) but others lived and worked in the city were the owned confectioneries, dry good stores and then groceries — their clientele were largely members of the larger dominant community: white Christians. More recently, I have been focusing on the African American community (which was know as the “Colored Community”) and believe I will have enough material for up to four two hour presentations. I will send you a prospectus when completed. As a spin-off, I have been exploring the growth of popular music in the state and starting in 1915 and the quickly growing it was jazz and what I am discovering the that colored jazz bands (from Omaha and other cities in the Upper Midwest were traveling through cities and towns of South Dakota early on). One of these groups which was extremely popular was Red Perkins and His Original Dixie Ramblers (I have one of their postcards probably from the mid 1920’s with a photograph of the band on the front and on the back below the printed “I’ll Be Seein’ You at” the typed note “Huron Dance Pavilion Thursday Dec. 31 New Years Eve”. Have the the names of many of these bands from newspaper ads and have found recordings of many (including the Dixie Ramblers) on Youtube videos!!!! When I get this together, I will send you a copy. Enjoy Stephen.