Editor's Note

Please consider this a belated addition to the excellent salon that Holly Genovese ran back in November/December on the work of Ibram X. Kendi and specifically on his award-winning Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. Those posts can be found here (Genovese), here (Robert Greene II), here (Genovese part 2) here (Rebecca Brenner), and here (Andrew Forney). Eran Zelnik also earlier conducted a very insightful interview with Kendi for the blog, which can be found here.

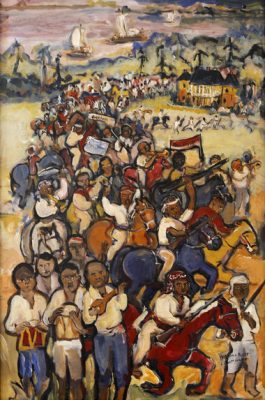

A painting of the 1811 slave revolt in Louisiana, by Lorraine Gendron

On this day of honoring Martin Luther King, Jr., I have been thinking about denial. Historical denial—like the way even major slave revolts such as the 1811 German Coast uprising still receive little attention—as well as the many different varieties of personal denial, those extenuations and deflections which ward off a full self-accounting, a wholesale review of where we really stand—and with whom. I’ve been thinking about this in part because I’ve been watching The Good Place, which in many ways is a show about shedding the layers of denial that we accumulate during a life, but also (and more directly) because of this extremely straightforward and extremely powerful op-ed, titled “The Heartbeat of Racism Is Denial,” written by Ibram X. Kendi in the New York Times.

Kendi argues that the denial of racism’s existence in U.S. society and persistence in American history is a “unifying” trait that “knows no political parties, no ideologies, no colors, no regions.” This is a challenging, uncomfortable point because—rather like the message of The Good Place—it is genuinely demanding: in order to break the unity which binds Americans together in a historical structure of racism, we must act positively. Inaction is also a form of denial: we cannot just wait and hope that someone notices us sitting quietly, being “not racist.” “Only racists say they are not racist,” Kendi says. “Only the racist lives by the heartbeat of denial. The antiracist lives by the opposite heartbeat, one that rarely and irregularly sounds in America — the heartbeat of confession.”

Kendi’s piece is focused on addressing the pervasiveness of denial rather than exploring its intricacies, but it does pause a moment to note how often Donald Trump has insisted that “I’m the least racist person that you’ve ever met

,” that “you’ve ever seen,” that “you’ve ever encountered.” It calls to mind the counterattack often made on activists of color: by focusing so much on race, they are “the real racists.”[1]

I’ve often struggled to understand the thought process that can produce an assertion like that: how can dismantling racial hierarchy be a form of racism, much less a more concentrated, more potent form of racism? And that is where I think Kendi’s work—both in this op-ed and in Stamped from the Beginning—is extremely helpful. “The principal function of racist ideas in American history,” he writes in Stamped from the Beginning, “has been the suppression of resistance to racial discrimination and its resulting racial disparities.” “The suppression of resistance”—racist ideas are suppressive, rather than constructive, about leaving a particular racial hierarchy intact rather than building it in the first place. They are about silencing dissent rather than speaking an opinion. Racist ideas allow discrimination to proceed unimpeded; they do not initiate discrimination.

This argument has not been without its critics among intellectual historians

, who may be uncomfortable with ideas serving such a secondary, ex post facto role. But when we think about denials like Trump’s, or the accusations that #blacklivesmatter activists are the “real racists,” what we can see is that the objective is not, ultimately, exculpation but rather “suppression of resistance.” “I’m the least racist person that you’ve ever met” isn’t an innocent plea—it’s a slander against anyone who would challenge the racial structure that has given Donald Trump power.

Now, as with most denials, this aggressive-passivity may not be entirely conscious. But what is surely conscious is the definition these people have in their minds of “racism.” Racism for them means trying to alter the racial status quo. Thus, in their minds, they truly are not racist: they’re not trying to change anything! It’s not as if they’re asking for more white skin privilege, so how can they be racist! Instead, for them it’s precisely those people who are looking to shake things up, who “see everything in terms of race,” who are racists. Racism isn’t inequality; it’s complaining and doing something about it.

Or, as Kendi says, the heartbeat of racism is denial. Its pulse is felt as a kind of irritability with “conversations about race,” with diversity talk, with affirmative action, with self-assertive people of color. Being “not racist” will not stop this heartbeat; only antiracism will.

11 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Andy, fantastic essay.

The framing of racism here — not as an active or constructive force, but as a stance that prevents the movement toward justice; that is, not as tending toward the actualization of something but rather preventing it — seems very similar to me to the classic Augustinian conception of evil: “Evil is nothing but the removal of good until finally no good remains.” This was of course not just a non-Manichean but an anti-Manichean conception of the problem of evil. There were not two opposed “forces” or “powers” or “camps” undergirding and and shaping the moral and material universe: just goodness and its perversion or privation.

Of course, neither you nor Kendi are suggesting that racism has no real effect in the moral or material world, any more than Augustine suggested that sin or evil had no power. But racism, like sin — or, as some aptly put it, racism as sin, America’s original sin — does not have the power to elevate anyone, to make anyone more of a person, more deserving, more meritorious compared to one’s fellows. Racism works by diminution alone, and it diminishes most of all those who harbor it by service or by silence — which is precisely why it’s so hard for those folks (or “us folks”) to let it go. Racism gives people the benefits of stature even as it chips away at it, it grants social standing for souls so degraded by it that they could not stand without it.

Anti-racism — not simply the negation of a negative, but the construction of justice and goodness as positive and substantial social relations — is the only way out of a system that does good to no one.

I think that’s a perfect connection to make! I have to confess (lol) that Augustine is one of the gaps in my education, so if you know of any works that you’d recommend–aside from reading the primary sources–please let me know!

Short answer: Peter Brown’s biography is still the gold standard. Gary Wills’s biography of Augustine, less scholarly but more urgent in some ways, is also an interesting read. I have J. O’Donnell’s, but haven’t read it yet, for reasons. There is a brand new translation of Confessions by Sarah Ruden — Peter Brown reviewed it glowingly in The New York Review of Books, and you can’t get a more authoritative endorsement of a work on (or of) Augustine than that. But I haven’t purchased it yet. However, given how fresh the text of the Odyssey has become in the hands of a skilled and scholarly woman translator, I think it might be worth it to give the Ruden translation a try. The one I know and love best is the Pine-Coffin translation, which used to be (and maybe still is) the translation used by Penguin books. (Ruden’s is available in the Modern Library.)

One of the more sparkling takes on the life of Augustine is, amazingly, a biography by Rebecca West. I enjoyed reading that, but I enjoy reading most anything by Rebecca West. I don’t remember the circumstances surrounding her taking up Augustine as her subject, but she had fun with him. And honestly, nothing could be more salutary for either our society or that Saint than for people to have fun with him.

In terms of his works, read Confessions cover to cover, skim City of God, read his Retractions, and perhaps most importantly (if neglectedly), read his sermons. There was a whole bevy of scribes writing down his sermons as he spoke them, for he usually delivered them extemporaneously. There’s probably no greater extant monument to the skill of a master rhetor — and before his conversion he served as the appointed orator of the (Western) Imperial Court — than Augustine’s sermons.

Fun fact: I was admitted to the graduate program at UT Dallas to continue working on my historical novel based on the life of St. Augustine. (Hence my idiosyncratic reasons for holding off on the O’Donnell biography–anxiety of influence.) Fortunately or unfortunately, while in graduate school I got sidetracked by history itself, thanks to Dan Wickberg’s course in 19th Century American Cultural History. Thus my fascination with Roman North Africa in Late Antiquity has been backburnered for now. But I have 45,000 words in a drawer, and I’ll take up the story again some time when I’m ready. First I have promises to keep, and miles to go before I sleep.

In any case, I think Augustine has been pacing through the dusty hallways of our collective American Mind, often unnoticed, but always there. Perhaps no single mind looms so large over “the West” — in a very real sense, we do not have Plato to thank for Augustine, but Augustine to thank for Plato.

Straussians, kiss my grits.

Reluctant to comment on Kendi’s work because I haven’t read it.

Would throw out the (unoriginal) point that a certain amount of legal and political struggle/disagreement about race and racism in recent decades, in the U.S. context at any rate, has revolved around the notion of “colorblindness.” Hence opponents of affirmative action, for example, say their ideal is a ‘colorblind’ society in which race is not taken into account in admissions decisions. Diversity may be a valuable goal, in this view, but colorblindness is the overriding ideal.

The other side, of course, argues that the historical legacies of oppression require positive steps to remedy and such steps take at least temporary precedence over colorblindness.

A related disagreement in a judicial context can be seen, e.g., in the 2007 Sup Ct case Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School Dist No. 1 where, according to L. Caplan’s summary, Roberts (for the majority) and Breyer (dissenting) disagreed about the meaning of Brown v. Bd. of Ed.. As Caplan glosses it (and I’m basically quoting him now), Roberts viewed Brown as outlawing discrimination, whereas Breyer viewed Brown as outlawing subordination, i.e., the perpetuation a caste system (or racial hierarchy, I suppose would be another way of putting it) rooted in the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow.

To end discrimination, one simply stops discriminating (i.e., stops taking race into account in whatever decisions or programs are at issue). Ending subordination, however, is more difficult and requires farther-reaching measures (and may well require talking race into account).

typo correction:

“taking” not “talking”

“Roberts viewed Brown as outlawing discrimination, whereas Breyer viewed Brown as outlawing subordination, i.e., the perpetuation a caste system (or racial hierarchy, I suppose would be another way of putting it) rooted in the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow.

“To end discrimination, one simply stops discriminating (i.e., stops taking race into account in whatever decisions or programs are at issue). Ending subordination, however, is more difficult and requires farther-reaching measures (and may well require taking race into account).”

That’s an extremely useful distinction–thank you! I think we can couple Roberts’s opinion in that case with his opinion in Shelby County. Clearly for him, racial discrimination was a historically bounded phase in the United States, and it has ended.

But I would also go further and argue that to read Brown or the Voting Rights Act as addressing discrimination only is to deny that they (or any other law) should address subordination, that is, that federal law has an interest in preventing or disrupting patterns of subordination. Which is a quite scary interpretation.

Also, Louis, I’m having trouble locating the Caplan article. Could you provide a citation–I’d love to read it.

Andy,

Agreed (and what you say about Roberts and Shelby County I think is right on point).

Caplan cite:

Lincoln Caplan, “A Workable Democracy: The optimistic project of Justice Stephen Breyer,” Harvard Magazine, March/April 2017.

It’s always good to see an essay like this that deftly deals with history and the present, and I feel all the more guilty for not having read Kendi’s book (yet). The argument the racism is primarily suppressive rather than constructive is interesting, but it seems to leave itself open to the Foucaultian Critique: namely, that racism, like power, both suppresses and constructs, that the two can’t be dirempted from each other. The resistance to a black family moving into a white suburb seems to come from both the desire to see them kept down, as well as the desire to see oneself as above or at the very least different from them. That is, at least in the construction of white identity (although I would be surprised if it was limited to only white people) there is a positive element to racism as well. This isn’t to discount Kendi’s thesis, but to expand it.

Apologies for the pretentious capitalization of critique, my autocorrect seems to be confused.

Thanks for this, Andy. I’ll have to read the Kendi piece, too. I made a few comments in this forum about Kendi’s book as I was reading it — and not even halfway through — but none since I finished it. A memorable and persuasive argument.