Editor's Note

This essay, by Nicholas Cox, is the third entry in our roundtable dedicated to John Reed’s classic book about the Russian Revolution, Ten Days That Shook the World. For the first and second contributions to the roundtable, check out the links below.

Andrew Hartman, Everybody Knew That Something Was Going to Happen, but Nobody Knew Just What

Nate Jones, Bolsheviki Appear to Control Everything Here

Nicholas P. Cox is currently the Program Coordinator for the History Department of Houston Community College. He has authored instructional supplements for Oxford UP’s Texas history textbook, Gone to Texas, is revising his first manuscript, a political biography of Colonel Richard M. Johnson of Kentucky, and is currently researching Reconstruction in the black-majority counties of late 19th century Texas. He has given presentations on his research and teaching at the AHA, SHEAR, TXSHA, ETHA, and HASH; referees article submissions for the Journal of South Texas; and reviews books for a number of journals. You can easily find him on Twitter @npcox or by email at nicholas.cox@hccs.edu.

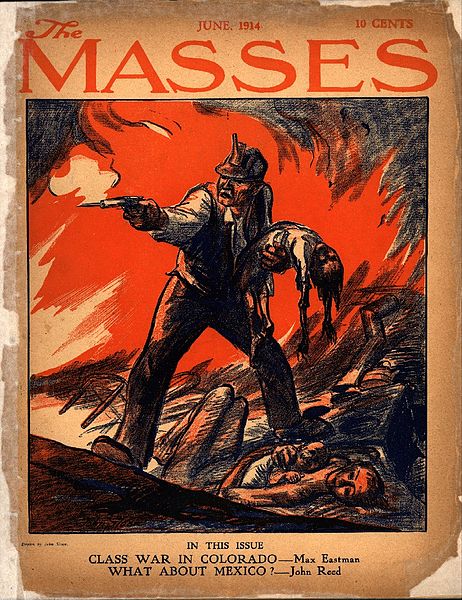

If the 100th anniversary is the opportunity for new readers to approach John Reed’s seminal Ten Days That Shook the World for the first time, or old lefties to revisit a classic, then I would certainly point them next to his journalism on the Mexican Revolution, World War One, and the Ludlow Massacre. Much of this writing appeared in the original The Masses (1912-1917) an essential journal of the Greenich Village bohemian left stifled and ultimately strangled by sedition charges during World War I. Writers like Reed and the editor Max Eastman sustained a pro-worker and avowedly Marxist editorial position in the successor, The Liberator. Issue are available online in cover-to-cover scans thanks to NYU and come highly recommended for understanding the old NYC left of the 1910s.

If the 100th anniversary is the opportunity for new readers to approach John Reed’s seminal Ten Days That Shook the World for the first time, or old lefties to revisit a classic, then I would certainly point them next to his journalism on the Mexican Revolution, World War One, and the Ludlow Massacre. Much of this writing appeared in the original The Masses (1912-1917) an essential journal of the Greenich Village bohemian left stifled and ultimately strangled by sedition charges during World War I. Writers like Reed and the editor Max Eastman sustained a pro-worker and avowedly Marxist editorial position in the successor, The Liberator. Issue are available online in cover-to-cover scans thanks to NYU and come highly recommended for understanding the old NYC left of the 1910s.

At this moment, we are living in an age of real anxiety about the future of mass audience magazines. Sure, The Atlantic or the New Yorker sustain wide spread support from readers of a certain non-confrontational, liberal intellectual and literary set, but broader, popular magazines that reach many more Americans are struggling to remain on the scene. Newsweek is long gone, and perhaps it’s too early to say, but how much longer can Time hold on? Conde-Nast and Hearst publishers are dropping titles, shedding their workforce, and this week’s sale of Time, Inc.’s properties including Time, Fortune, Sports Illustrated, and others raises concerns anew about both, their future viability as profitable ventures or as contributors to American culture in any significant way. For those of us more predisposed toward engaged or combative political news and thought we are regularly reminded that there is a boundless quantity of thoughtful writing by journalists, activists, and academics online in spaces like this one. We are reminded that we are in a flourishing age of small magazines with relatively new, fresh, smart, and substantial, as well as occasionally elegant, periodicals such as n+1 or Jacobin. Undoubtedly, in print or not, social media has gathered a larger audience for provocative and thoughtful writing.

The 1930s offer a fascinating parallel. Sure, the economic collapse of the Great Depression eviscerated much of the profitability and consumption of popular press magazines and newspapers in the 1930s. And yet, the Depression itself called for a radical reappraisal of America’s commitment to market capitalism as engaged, and often young journalists, novelists, and academics sought to push for increasingly radical reforms. Not surprisingly, John Reed’s activist journalism became a model for left-leaning, especially Communist-leaning or joining writers and artist. As Granville Hicks, Reed’s biographer and later director of the Yaddo artist colony, wrote in his introduction to the 1930s Modern Library edition of Ten Days That Shook the World, Reed “was a hero.” A self-described “out-of-town member of the John Reed Club of New York City,” Hicks would eventually abandon the Communist movement following the 1939 Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact and move further into the anti-Communist camp as Stalin consolidated power. My interest in these fellow travelers and John Reed Club of New York writers developed as a tangent to a larger project I began in grad school, and hope sometime to return to, on Theodore Dreiser, the Old Left, and the Great Depression. This reappraisal of Reed and Ten Days That Shook the World seems like a worthwhile opportunity to speak a bit about his posthumous impact on radical writing in the 1930s.

When Reed died in Russia of typhus in October 1920 he was perhaps the best American representative of the international, cosmopolitan ambitions of global communism as imagined by the Comintern. He traveled to Russia in 1917 to report on the ongoing eastern front of the Great War, observed the Bolshevik Revolution, praised Lenin and Trotksy, and (like his opposition to American intervention in Mexico in 1914) sustained an anti-intervention position against any Allied attempts to roll back the Communist Revoluion. He saw no good could come of American participation in the Revolution. Reed joined the Red Guards, participated in the Second Comintern Congress, and began the active organization of an American communist party in NYC. Among the old left, his burial in the Kremlin with full Soviet honors seemed more than appropriate for an American who had made such a large effort to advance what Reed believed to be a necessary, revolutionary struggle for American workers.

Along the way Reed had the most interesting of friends. The Masses and other literary and journalistic “small magazines” cultivated an exceptional stable of talent including John Dos Passos, Langston Hughes, Ernest Hemingway, Richard Wright, Eugene O’Neill and many more literary lights of the 1920s. Radical reformers and activists including Margaret Sanger, Emma Goldman, Bill Haywood and others passed through the editorial offices and joined Eastman, Reed, and others in the cafes in the Village popular among the radical left.

In 1926 Joseph Freeman, Mike Gold, and Walt Carmon revived the The Masses. As the publication most significant to distributing John Reed’s reporting before his death in 1920, the New Masses explicitly drew on his example to establish its own tone and purpose in the Jazz Age. The New Masses offered a continued Marxist critique of politics and society in the Roaring Twenties, and by the 1930s promoted the injection of class conscious themes into popular art, music, and literature as part of the broader Popular Front cultural movement. Reed remained the model for engaged political writing central to The New Masses editorial view. In 1929 Carmon encouraged young writers in his journal’s orbit to found a John Reed Club to cultivate writing and art in Reed’s spirit. Many young writers did just that, and often their work appeared in The New Masses.

The most significant of the Clubs was centered, of course, in New York City and from 1929 to 1935 promoted a series of modern art exhibits. The Clubs spread to most major cities, most significantly Chicago, San Francisco, and Boston, but ultimately about thirty chapters have been identified by literary historians of the left such as Alan Wald. Club members and editors of The New Masses such as Gold and Freeman pushed established artists such as Theodore Dreiser to take more radical public positions alongside the communist movement on social crises such as the Scotttsboro case in 1931. Richard Wright, whose involvement in the Chicago John Reed Club paved the way for his earliest nonfiction writing in The New Masses, developed his earliest stories and wrote his first 1930s novel while engaged with Club politics. It dissolved shortly after Wright’s departure for New York. In New York, members of the Club such as Philip Rahv, William Philips, and Joseph Freeman founded The Partisan Review in 1934 with an explicit mission to make politics central, leaving The New Masses to continue focusing on literature, art, and culture. Needless to say, Partisan Review and The New Masses would remain central to Great Depression era radical writing and thinking.

From the founding in 1929 onward to the establishment of chapters around the nation, the John Reed Clubs were always envisioned as a media effort subordinate to the Communist Party USA. In 1936 the John Reed Clubs dissolved, finding its literary and visual artists forwarded by the CPUSA into either the Communist League of American Writers or the American Artists’ Congress. Like The Partisan Review, the League and Congress embraced a broader, less sectarian Popular Front approach in the 1930s. Their commitment to anti-fascism was largely shared by past Club members. International communism’s broader effort to halt Franco in Spain led many of the John Reed Club writers and artists to advance the Soviet critique of fascism in the Spanish Civil War in their art and writing after 1936. The relationship of the American left and communist sympathizers was, as widely reported and memoired, deeply disturbed by Stalin’s conduct in the 1930s, the Soviet-Nazi non-aggression pact, as well as the Russian invasion of Finland. Many fellow travelers and supporters of Lenin or Trotsky fell away in the 1930s in response to Stalin’s rise. The Partisan Review, which had folded in 1936 after publishing only a few issues in its first two years, reemerged a year later energized by their disgust at the purges in Stalin’s Russia as the leading voice of the anti-Stalinist left. The Artists’ Congress folded in 1942 and the Writers’ League in 1943; with their dissolution any vestiges of the John Reed Clubs vanished as an organization within the Communist Party USA. The New Masses folded in 1948 leaving The Partisan Review as the single most important legacy of the Clubs, but during and after World War II it had embraced an explicitly anti-Stalinist editorial position.

In our era, there is enough of an interested audience of left-leaning readers to sustain several solid lefty magazines, small journals, and web spaces, and surely these fill a similar niche as The Masses or The Partisan Review as they sustain creative, thoughtful reporting about our moment. Yet it remains to be seen if a lasting coterie of seminal writers will match the constellation of journalists, novelists, and painters who found John Reed’s life inspiring enough to form their own literary-political movement. Often sheltered from the market for popular writing, increasingly contemporary left-leaning journals seem over-reliant on academics to be both the producers of content and the consumers of content. This blog certainly aspires to reach beyond an insular group of academics, surely, as do old and new lefty publications. Yet Reed believed, along with The Masses editor Max Eastman, that their work depended on centering the voices of working people along with a fidelity to the party line, perhaps two compulsions anathema to the left today, even if it finds itself increasingly marginalized to academia. Perhaps we can take a cue from The Masses and the Clubs and cultivate exceptionally talented artists, engage immediately with politics as it unfolds, break down divisions between scholarship, journalism, and literature. But if you’d like to know just how to do that, as soon as you’ve revisited Reed’s classic on the Russian Revolution, dive into Reed’s vast work beyond his magnificent Ten Days That Shook the World. But take some time to read his literary acolytes, too, especially during the tumultuous 1930s.

0