Never are we able to read as much as we want; more distressingly, perhaps, we don’t always read the things we tell ourselves we want to read. An interesting exercise in place of the typical “my year in reading” might be to itemize the books we meant to read—but did not. Perhaps that would be too much like confession, but whatever the reason, I will be conventional and share merely those great books I did read this year rather than those possibly greater ones I did not.

Never are we able to read as much as we want; more distressingly, perhaps, we don’t always read the things we tell ourselves we want to read. An interesting exercise in place of the typical “my year in reading” might be to itemize the books we meant to read—but did not. Perhaps that would be too much like confession, but whatever the reason, I will be conventional and share merely those great books I did read this year rather than those possibly greater ones I did not.

If there is one book I read this year that I would urge you to read immediately, it is Valeria Luiselli’s Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions. A concentrated act of testimony and advocacy, Luiselli explains how she became a sort of intake counselor cum translator for nonprofit legal services trying to prevent children who are refugees from Central America from being deported. Many of these children have endured soul-crushing physical hardship in escaping from semi-military gang violence and passing through the gauntlet of horrors that comes with the journey al norte. Their ability to put their stories into words—and Luiselli’s challenge in turning those words into a narrative that would qualify them for asylum—is strained both by the unreality of these experiences as well as by the brute fact of their youth. Luiselli tries to tell their story not only to the immigration officials but also to us, explaining what kind of crisis this is, why it exists, and what kind of efforts are out there to meet it. Simultaneously with her work as a translator, Luiselli was also teaching a Spanish course in New York, and woven in with her explanations of this crisis is a narration of her effort to educate her own students about the crisis and their response. These passages are a kind of master class in pedagogy, and among the most hopeful and inspiring things I’ve read in a long time about a professor’s classroom experience.

Along with Luiselli, my greatest discoveries this year were the novelists Ali Smith and Han Kang. I read Smith’s most recent novel, Autumn, just a couple of weeks ago and was pleased to see it ended up on the New York Times’s year-end top ten. It really is that good. Billed as the first “post-Brexit” novel, it does capture the spirit of the moment in all its disbelief, indignation, repulsion, and exhaustion. But it is also—like all Smith’s work—intricate and playful, wise and warm, as much an affirmation of human creativity and stubborn joyfulness as it is a denunciation of the intolerance and provinciality of the Leave mob in England. It demands that we recognize an exuberant and imperishable human desire to share our latent talents with others. About Kang I have less to say, other than to note that I’m still reeling from the experience of reading her two novels, Human Acts

Along with Luiselli, my greatest discoveries this year were the novelists Ali Smith and Han Kang. I read Smith’s most recent novel, Autumn, just a couple of weeks ago and was pleased to see it ended up on the New York Times’s year-end top ten. It really is that good. Billed as the first “post-Brexit” novel, it does capture the spirit of the moment in all its disbelief, indignation, repulsion, and exhaustion. But it is also—like all Smith’s work—intricate and playful, wise and warm, as much an affirmation of human creativity and stubborn joyfulness as it is a denunciation of the intolerance and provinciality of the Leave mob in England. It demands that we recognize an exuberant and imperishable human desire to share our latent talents with others. About Kang I have less to say, other than to note that I’m still reeling from the experience of reading her two novels, Human Acts

and The Vegetarian.

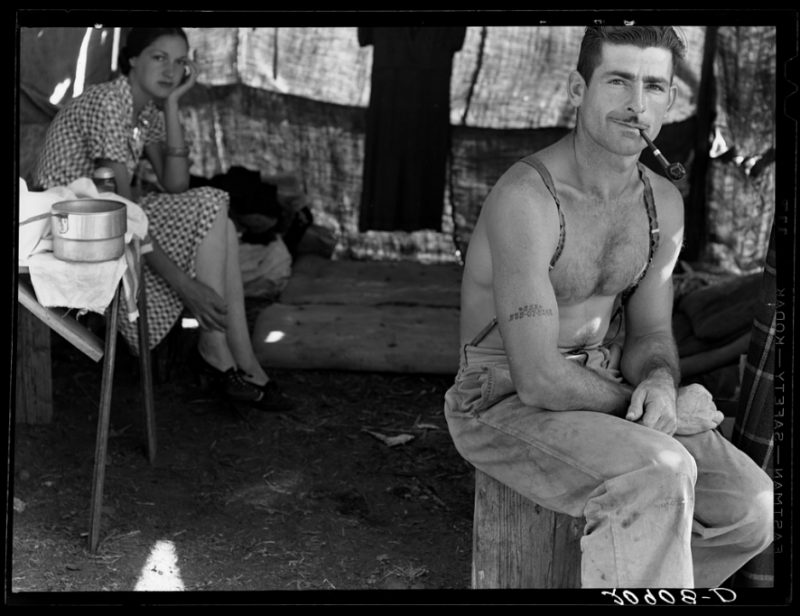

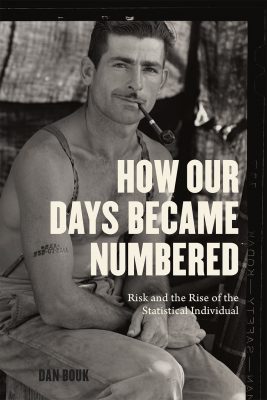

Among the monographs which similarly bowled me over with their brilliance are Melinda Cooper’s Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism (about which I wrote earlier this year) and Dan Bouk’s How Our Days Became Numbered: Risk and the Rise of the Statistical Individual. Bouk’s work is an intellectual history of capitalism, but like a number of such studies, he carries it off with a poetic verve and elegance that transcends its material, expressing not only the inner logic of capital but also its hidden melodies, little patches of fancy and wonder that defy the Weberian gloom of iron cages and profit motives. I would put his study alongside three of my favorites, Scott Sandage’s Born Losers: A History of Failure in America

, Richard Ohmann’s Selling Culture

, and Lendol Calder’s Financing the American Dream.

Finally, I’d like to make a pitch for another novel that I think may appeal to readers of this blog: the Irish author Sebastian Barry’s Days without End. A novel whose hero is an Irish immigrant fighting in America’s wars against Native Americans and for the Union, Days without End recreates the nineteenth century as a moment of almost infinite possibility and shameful brutality. Historians often struggle to convey a palpable sense of contingency—in our articles and monographs, in our lectures, in our own minds. The novelist has it easier, but Barry creates a sense of openness and even innocence that is breathtaking: an idea that the history of the West could have been different, could have been less violent, more just, full of compassion rather than blood. Without in the least imagining the US Army—the setting for a good part of the novel—as a benevolent institution, the novel refuses to imagine enmity between Native Americans and whites as instinctual or violence as inevitable. (Southerners, on the other hand, come off worse.) Not quite a direct response to the “new,” post-Unforgiven Western of the past twenty-five years, Days without End nonetheless reveals the persistent rigidity of the Western mythos: while new Westerns may shift the faces around, a frustratingly tight set of well-defined and immobile roles remain the basic building blocks of these “revisionist” works—men and women, cowboys and Indians. Days without End is, in contrast, all fluidity.

And now, I’d love to hear about some of your favorite books of the past year: please share in the comments!

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I read a lot due to podcasting and my own research and fortunately every year there is great number of really enjoyable books. I tend not to take time to read for pleasure. I figure that there are many great books that can serve double duty. I am personally partial to biographies that I started reading in my teens. They provided models of what was possible when I didn’t see much around me that I wanted to emulate. This year I loved Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray by Rosalind Rosenberg; Women in the World of Frederick Douglas by Leigh Fought; Oneida: Free Love and the Well Set Table by Ellen Wayland-Smith; This next one is older but amazing narrative writing, Scars of Sweet Paradise: The Life and Times of Janis Joplin by Alice Echols. Of the weightier monographs, The Law and Modern Mind by Susanna Blumenthal stands out and needs more attention. Most of these have a podcast you can find on my website under “media projects.” Looking forward to see what others have read that I missed.

Fun post, Andy. Thanks for the recommendations.

I’ve blogged a lot of my year in reading — this summer it was academic novels like Stoner, Lucky Jim, and The Paper Chase (I think I never got around to writing about one of those).

I read some wonderful historiography — the first volume of Donald R. Kelley’s three-volume survey of Western historiography, Faces of History, and then that wonderful look at the history of Anna Komnene by Leonora Neville, Anna Komnene: The Life and Work of a Medieval Historian.

As you know, I’m reading through “the Stanford canon” — traipsing through Plato now, to the chagrin of some Straussian somewhere I’m sure.

Here I would put in a special plug, as everyone else is, for Emily Wilson’s translation of the Odyssey. What a gift to the anglophone world. It is a joy to read.

Along with you and others, I read Nancy MacLean’s Democracy in Chains–but I need to be careful here, because if you say “Nancy MacLean” and “James Buchanan” three times in the same sentence, Kochlings show up and start spamming your threads.

I read Heather Ann Thompson’s Blood in the Water. First of all, “wow” about that as a work of history — but “wow” also about the way she tackles historiographical problems in the text. Really fantastic.

I am almost finished with Ibrahim X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning, as well as with Christine Stansell’s The Feminist Promise. Those two are interesting to compare in terms of scholarly writing for a broad audience. Kendi must approach his through-line with a relentless clarity, to clear out the little niches of “nuance” where we sometimes like to ensconce our historical favorites — his prose is power itself. Stansell has approached her task from the opposite direction — to give nuance to an oft-simplified through-line. She writes beautifully even as she wades into the fray herself. It’s really some of the loveliest prose I’ve read all year.

I am heading out of the country this weekend for a much-needed vacation, sans spouse and kids, and I’m taking along Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, Treva B. Lindsey’s Colored No More, and Johann Neem’s Democracy’s Schools. Not sure how much reading I will get done, but I have to at least give myself a chance.

I am half-tempted to just stay gone and have my family mail me the rest of my books. But America is my home and my heartbreak, so I will come back and try to tell the story of it all over again for another bunch of students who take my class because they have to and then at the end are glad that they did.

And just yesterday I read what apparently everybody else in the universe was reading, “Cat People,” a short story in the New Yorker. Here is my quick takeaway, which doubles as advice on sex and romance. One of my friends suggested, an advice column (“Bad Advice”?) could be my AHA “Plan B.”

My Plan B is an academic novel — already working on it.

I read Lord Jim this summer, which I’d never read in school, unlike many people. Some great passages. Also read this year: Enzo Traverso’s Fire and Blood, Nancy Rosenblum’s Good Neighbors, and Michael Franks’ well written and sometimes moving family memoir The Mighty Franks (disclosure: am acquainted with the author). Recently bought the second ed. of The Reactionary Mind, which Andy S. has already blogged here about. Favorite Burke line (quoted in the chapter “Burke’s Market Value”): “I have strained every nerve to keep the duke of Bedford in that situation which alone makes him my superior” (omitting Burke’s comma after “situation” because the sentence flows better without it).

I’ve blogged here about the books that meant the most to me — The Great Derangement by Amitav Ghosh, Sapiens by Noah Yuval Harari, inherit the Holy Mountain by Mark Stoll, and The Patterning Instinct by Jeremy Lent. Still not finished with Kendi’s Stamped at the Beginning, but in the final chapters and admire it more and more. In terms of just plain pleasure, I listened to the audio version of The Goldfinch after reading it in print back when it came out. Just as compelling as the first time …

I just picked up Days Without End because of this post. Only ten pp. in, and I can tell this is good. (The cadences somewhat echo Cormac McCarthy, though that may be where the similarities end.) S. Barry can write.