Editor's Note

This post, by Nate Jones, is the second entry in our roundtable on John Reed’s Ten Days That Shook the World. For the first essay, by me, go here.

Nate Jones is the Director of the Freedom of Information Act Project for the National Security Archive. Nate’s book Able Archer 83: The Secret History of the NATO Exercise That Almost Triggered Nuclear War examines the intersection of Cold War animosity, nuclear miscalculation, and government secrecy.

Enjoy! Andrew

“Bolsheviki appear to have control of everything here” moving “faster and faster towards – what?” US Diplomats’ and John Reed’s accounts of the 1917 Russian Revolution

“Bolsheviki appear to have control of everything here” moving “faster and faster towards – what?” US Diplomats’ and John Reed’s accounts of the 1917 Russian Revolution

By Nate Jones

George F. Kennan, cherished State Department diplomat to the Soviet Union and father of the American doctrine of Containment toward the USSR, has written that John Reed’s account of October Revolution “rises above every other contemporary record for its literary power, its penetration, its command of detail” and would be “remembered when all others are forgotten.” [1]

Kennan’s predecessors on the ground in Russia during the upheaval did not view Reed as kindly. On New Year’s Eve, 1918 – when the US and Bolshevik government in Russia maintained fraught relations – US Ambassador David Francis wrote to Secretary of State Robert Lansing that he was “endeavoring… to get Lenin to revoke Reed appoint [as Soviet consul in New York] with fair prospect of success.” After Reed returned to the United States in April 1918, federal authorities seized his impressive archive of Soviet newspapers, circulars, published speeches and proceedings, and posted proclamations –upon which Ten Days That Shook the World would ultimately be largely based upon. Despite promising that Reed’s archive would be returned to him the next day, US authorities held it for over six months.

The US government’s ultimately successful effort to remove Reed as the Soviet’s representative in the US is the only time that his name is mentioned in the State Department’s Foreign Relations of the United States volume on the Russian Revolution. [2] But although he is largely absent from the official, US-government-published diplomatic history of US-Russian relations, Reed’s descriptions of “‘Red Petrograd,’ the capital and heart of the insurrection” enhance and amplify the diplomatic accounts of the Revolution. In fact, the two accounts – of drastically differing prose –complement each other extraordinarily well.

In their own way, both accounts report the tense, anxious, fearful, hopeful, unknown atmosphere in Petrograd during the waning days of October, 1917. On October 27, 1917 (October 14th using the Julian calendar; henceforth this essay will use the modern dates) the American Ambassador in Russia, David Francis, telegraphed his Secretary of State Robert Lansing:

Quiet here, no manifestations of uneasiness notwithstanding rumors that the workmen armed organized and will have material assistance from Krondstadt [sailors]. Another rumor that first Bolshevik act will be arrest of Provisional Government [established after the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in March 1917] and their incarceration…Government has announced intention to suppress Bolshevik manifestation peacefully or otherwise. [3]

One the Eve of the October Revolution Reed described the same unease, using the words of a journalist – with a dash of avant garde – rather than a diplomat:

At Smolny [4] [a former convent at the edge of the city that was the intellectual and tactical headquarters of the uprising] there were strict guards at the door and outer gates, demanding everybody’s pass. The committee-rooms buzzed and hummed all day and all night, hundreds of soldiers and workmen slept on the floor, wherever they could find room. Upstairs in the great hall a thousand people crowded to the uproarious sessions of the Petrograd Soviet.

Gambling clubs functioned hectically from dusk to dawn, with champagne flowing and stakes of twenty thousand rubles. In the centre of the city at night prostitutes in jewels and expensive furs walked up and down, crowded the cafes…

Monarchist plots, German spies, smugglers hatching schemes…

And in the rain, the bitter chill, the great throbbing city under grey skies rushing faster and faster towards – what? [5]

Both the State Department dispatches and Reed’s Ten Days (and I eagerly hope that my esteemed roundtablists have been able to identify which, exactly, were the ten days that Reed chronicled; I could not) seem to identify three key points which led to the success of the Bolsheviks: 1) The conversion and alliance of the Petrograd garrison and its 60,000 soldiers to the Bolshevik cause, 2) The successful – if surprisingly easy – “storming” of the Winter Palace, and 3) the decision of the railroad workers union not to transport Kerensky and his army to Petrograd to put down the revolution.

By the time Ambassador Francis’s October 27 telegram had reached Washington – transferred via telegraph as all the Department of State’s messages cited here were – on November 2, a tremendous, ultimately fatal blow had been struck against the Provisional Government. After delegations from the Petrograd Soviet [6] asked to confer with the General Staff and Soldiers Committees fighting on the Eastern Front of the First World War were rebuffed (“We do not recognize you; if you break any laws, we shall arrest you,” according to Reed), the Petrograd garrison passed a resolution:

‘The Petrograd garrison no longer recognizes the Provisional Government. The Petrograd Soviet is our Government. We will obey only the orders of the Petrograd Soviet, through the Military Revolutionary Committee [controlled by the Bolsheviks].’ The local military units were ordered to wait for instructions from the Soldiers’ Section of the Petrograd Soviet.

On November 3, the garrison affirmed, “the Petrograd garrison promises [the Military Revolutionary Committee] complete support in all its actions, to unite more closely the front and the rear in the interests of the Revolution. The garrison moreover declares that with the revolutionary proletariat it assures the maintenance of revolutionary order in Petrograd. Every attempt at provocation on the part of the … bourgeoisie will be met with merciless resistance.”

According to Reed, “now conscious of its power,” the Military Revolutionary Committee controlled by the Bolsheviks, “gave orders not to publish any appeals or proclamations without the Committee’s authorization. Armed Commissars visited the Kronversk arsenal and seized great quantities of arms and ammunition, halting a shipment of ten thousand bayonets which was being sent to Novotcherkask, headquarters of [General] Kaledin. Suddenly awake to the danger, the [Provisional] Government offered immunity if the Committee would disband. Too late.”

The embassy’s reporting on the garrison’s conversion to the revolution did not match Reed’s detail or perceptiveness. On November 2, Ambassador Francis wrote to the Secretary of State:

Press reports great majority of soldiers in Petrograd garrison have passed resolutions to obey Soviet if demonstration ordered. Right young men from officer’s military school just arrived Embassy saying ordered here by Petrograd staff to protect Embassy and guards sent to all foreign missions. Think this not significant but merely precaution.

In fact, the situation in Petrograd was well past the stage of precaution. Too late.

The FRUS volume includes several absolutely remarkable dispatches conveying the November 7 fall of the provisional government to Washington. The first account describes how the US diplomatic corps learned of the fall of the Kerensky government by a chance meeting on the Petrograd street:

[The Secretary of the US Embassy] Whitehouse, en route to the Embassy this morning, was accidently met by aide-de-camp of Kerensky and several [minutes afterwards by] latter who told him that he was hurriedly leaving [7] to meet regular troops on the way to Petrograd to support Government which would otherwise be deposed. He acknowledged that Bolsheviki control city and that Government powerless without reliable troops as there are few here of that nature. He said that he expected that the remainder of Ministry would be arrested to-day and told Whitehouse to convey request to me not to recognize Soviet government if such is established in Petrograd as he expected whole affair to be liquidated within five days but this in my judgment depends on number of soldiers who will obey…

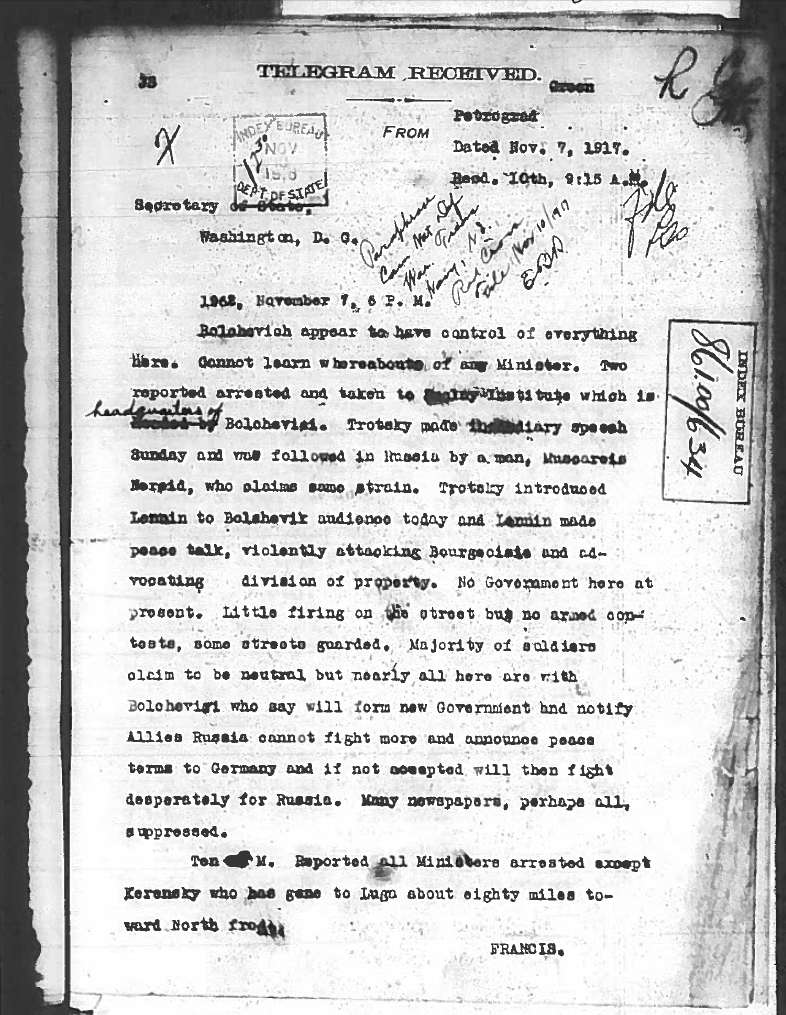

A follow-up telegram also written at 6 pm and updated at 10 pm – before the ministers in the Winter Palace were actually in Bolshevik custody – reported: “Bolsheviki appear to have control of everything here.”

Just after 2:00 AM in the early morning of November 8, the Bolshevik raiders climbed the Stairs of the Winter Palace and flung open the doors of a second story room and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko declared, “You are all under arrest.” [8] That afternoon the US embassy in Sweden telegraphed Washington announcing the end of the Provisional Government:

Because of the possibility of telegraphic communication between our Embassy in Russia and the Department being interrupted due to latest developments in Petrograd, I am sending the following which appear in the press this morning as dispatches from the Russian official telegram bureau. According to these telegrams Bolsheviks have made successful coup d’état; have taken the State Bank, telegraphs, telegram bureau and have arrested certain members of Kerensky’s government.

During the afternoon of November 7, Reed was actually able to gain entrance to the Winter Palace simply by putting on an official air, waving his American passport and yelling “official business!” His description of the soldiers tasked to guard the seat of the old Russian monarchy served as a metaphor of the current state of the Russian Empire… and foretold its fall hours later:

At the end of the corridor was a large, ornate room with gilded cornices and enormous crystal lustres, and beyond it several smaller ones, wainscoted with dark wood. On both sides of the parquetted floor lay rows of dirty mattresses and blankets, upon which occasional soldiers were stretched out; everywhere was a litter of cigarette-butts, bits of bread, cloth, and empty bottles with expensive French labels. More and more soldiers, with the red shoulder-straps of the yunker schools [military academies], moved about in a stale atmosphere of tobacco-smoke and unwashed humanity. One had a bottle of white Burgundy, evidently filched from the cellars of the Palace.

But taking control of Petrograd and holding it – much less all of Russia! – were two very distinct things. Reed’s reporting echoed the sentiment that Kerensky’s aid had told the US diplomats that morning, “That the Bolsheviki would remain in power longer than three days never occurred to anybody – except perhaps to Lenin, Trotsky, the Petrograd workers, and the simpler soldiers.”

The final key moment of the revolution – grasped and reported by the diplomats and by Reed – was the decision of the railway workers union (the Vikzhel) not to transport Kerensky’s troops from the Northern front to Petrograd. The embassy reported this key fact to Washington, but not its implication, on November 13: “Quiet here probably result of announcement of railway union that if civil war not ended immediately railroads would cease to operate throughout Russia.”

Reed more precisely reported the nuance of the Vikzhel’s position. [9] In addition to helping the Bolsheviks by halting Kerensky’s advance, it was also harming them by not allowing food or other goods into the city. Reed describes that the railway workers union halted transportation to exercise its political power – its spokesperson described the union as “the strongest organization in Russian” – and an attempt to gain larger representation in the new revolutionary government. Nonetheless, as the Vikzhel tried to use its power to forge “a government based on the confidence of all the democracy,” Kerensky had lost the railways, and his ability to retake Petrograd. The Bolsheviks would hold the city for 74 years.

It is a pity that the American diplomats in Russia during the revolution could not read Reed’s reporting in real time; their understanding of the upheaval would have been much fortified. Nevertheless, the State Department’s accurate – if colorless – reporting to Washington was ultimately proven more correct than Reed’s on two of the largest questions of the Russian revolution.

The first: the terror. Reed openly acknowledges that he did not attempt to chronicle the revolution as an impartial observer. “Adventure it was,” he wrote in his preface, “and one of the most marvelous mankind ever embarked upon.” But as he chronicled this adventure, he could not help but document the ominous signs of the terror that accompanied it.

The terror began moments after the Bolsheviks seized power. At the Second Congress of Soviets, Trotsky issued an icy, foreboding condemnation to the Bolsheviks’ former allies, the moderate socialist parties – of which he was once a member. Reed recounts:

And Trotsky, standing up with a pale, cruel face, letting out his rich voice in cool contempt, ‘All these so-called Socialist compromisers, these frightened Mensheviki, Socialist Revolutionaries, Bund—let them go! They are just so much refuse which will be swept into the garbage-heap of history!’

But here, unlike elsewhere, Reed does not editorialize. Instead he quickly transitions to an exciting tale of accepting a workman’s offer to jump into a motor truck “bumping at top speed down Suvorovsky Prospect” to the Winter Palace and crowds that had gathered around it.

In a later instance, Reed, writing as a correspondent for the socialist paper The Masses, serves as loyal stenographer to Lenin. The leader of the new revolutionary government, “each sentence falling like a hammer-blow,” declared the end of the free press. Lenin explained that “to tolerate the bourgeois newspapers would mean to cease being a Socialist.” Reed, again without editorializing, dutifully reports that on November 17, 1917 the free press in Russia was abolished by a vote of 34 to 24.

The State Department – of course also biased in its reporting – did warn of the risk of terror throughout the revolution and after it. In a September 3, 1918 telegram – seven years before Stalin’s [10] ascension – starkly warned the Secretary of State that “an openly avowed campaign of terror

” had begun:

Thousands of persons have been summarily shot without even the form of trial. Many of them have no doubt been innocent of even the political views which were supposed to supply the motive of their execution… Socialists, once coworkers with the Bolsheviki, have turned against them the methods by which they formerly attacked the tyranny of the Tsars. ‘Mass terror’ is the Bolshevik reply. [11]

The second instance that the diplomats’ analysis proved more insightful than Reed’s was the key question of the prospect for worldwide revolution. Reed insightfully reports that the Bolsheviks honestly believed that the Russian revolution was just a step on the way to world-wide socialist revolution and self-governance by workers. One key article by a Bolshevik paper in Reed’s archive declared that once established, the Soviet Russian revolutionary government would “appeal over the heads of the diplomats directly to the German troops, fill the German trenches with proclamations in the German language…Our airmen would spread these proclamations all over Germany.”

In an October 30th interview with Reed, Trotsky reiterated that the Soviet revolutionary government would, “be a powerful factor for immediate peace in Europe; for this Government will address itself directly and immediately to all peoples, over the heads of their Governments…At the end of this war I see Europe recreated, not by the diplomats, but by the proletariat. The Federated Republic of Europe—the United States of Europe—that is what must be. National autonomy no longer suffices. Economic evolution demands the abolition of national frontiers. If Europe is to remain split into national groups, then Imperialism will recommence its work.”

After the Bolsheviks took Petrograd, Lenin predicted “that revolution will soon break out in all belligerent countries; that is why we address ourselves to the workers of France, England, and Germany…The revolution of November 6th and 7th, has opened the era of the Social Revolution… The labor movement, in the name of peace and Socialism, shall win, and fulfill its destiny…”

The American diplomats were far more concerned with the implications of Soviet Russia making a separate peace with Germany and ending the war on the Eastern front than with the Petrograd Revolution spreading to the American masses.

In fact, on November 2nd, the Secretary of State telegraphed the embassy in Russia a statement by Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor rebuffing a Russian invitation to “an international conference of workmen and socialists from all countries.”

Gompers wrote: “That we regard it as untimely and inappropriate, conducive to no good result, but on the contrary harmful, to hold an international conference at this time or in the near future with the representatives of all countries, including enemy countries, and we are constrained therefore to decline at this time either to participate in or to call such a conference.” American diplomats correctly ascertained that despite the genuine grievances and unrest of their working classes, there was little risk of the White House succumbing to the fate of the Winter Palace.

At six in the morning of November 8, four hours after the ministers of the Provisional Government in the Winter Palace were finally arrested, Reed witnessed “a faint unearthly pallor stealing over the silent streets, dimming the watch-fires, the shadow of a terrible dawn grey-rising over Russia.”

It was at that moment Reed asked himself:

So. Lenin and the Petrograd workers had decided on insurrection, the Petrograd Soviet had overthrown the Provisional Government, and thrust the coup d’etat upon the Congress of Soviets. Now there was all great Russia to win—and then the world! Would Russia follow and rise? And the world—what of it? Would the peoples answer and rise, a red world-tide?

Three years later, Reed died of typhus in Moscow and was buried under the Kremlin wall necropolis.

The answer to his question would have devastated him.

[1] George Kennan. Russia Leaves the War: Soviet-American Relations, 1917–1920, (Princeton University Press, 1956). pp. 68–69.

The Foreign Relations of the United States series “presents the official documentary historical record of major U.S. foreign policy decisions and significant diplomatic activity. The series, which is produced by the Department of State’s Office of the Historian, began in 1861 and now comprises more than 450 individual volumes.” The documents quoted here were written too early to be technically “classified” but they certainly would have been tightly held and not available to the public at the time of the revolution.

[3] Thanks to the Emma Sarfity of the National Security Archive for retrieving the original copies of these dispatches from the US National Archives. They can be found in Department of State Microfilm Publication M316, roll 10. Among the documents quoted are 861.00/632, 861.00/634, and 861.00/635.

[4] The Smolny Convent sits adjacent to the Smolny Cathedral, where your author studied Russian as a student in the fall and winter of 2003.

[5] John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World, (Boni & Liveright, 1919).

[6] In this context, “Soviet” is best described as a workers’ council, perhaps a type of Russian union.

[7] In fact, Kerensky had fled Petrograd in a Renault seized from outside the American Embassy. The car, with its American insignia, no doubt help Kerensky evade searches by the Red Guards. Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891-1924,

(Penguin, 1997), 486.

[8] Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891-1924, (Penguin, 1997), 491.

[9] Reed, who made the dangerous trip to the front, also credits the heroics of the Bolshevik troops that repulsed Kerensky and others who switched to the revolutionary side as the general attempted to march on Petrograd from Gatchina.

[10] Apparently, Stalin was such a minor figure in the revolution that his name is mentioned just twice in Ten Days, both times in reproductions of Bolshevik pronouncements, not in Reed’s description of the events and actors.

[11] The Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs Georgy Chicherin replied to these charges by framing the terror in Moscow in the context of the atrocities of the White Army and arguing that the situation of a bloody, revolutionary civil war could not help but include terror as a natural element.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

@N. Jones

Thank you, belatedly, for this post. V. interesting; great use of the FRUS documents.

I haven’t yet gotten to the third and final post in this roundtable, but one question that I have as a result of the first two installments is about the sources of Reed’s sympathy for the Bolsheviks and hope for world revolution. Andrew H’s post mentioned Reed’s experiences with two strikes in the U.S. and their suppression (esp. a Colorado miners’ strike) and also his experiences in Mexico. But presumably not everyone would have drawn quite the same political conclusions from these experiences as Reed did. So why did he become a Leninist as opposed to, say, a Debsian socialist? I imagine the Reed biographies go into this…