Editor's Note

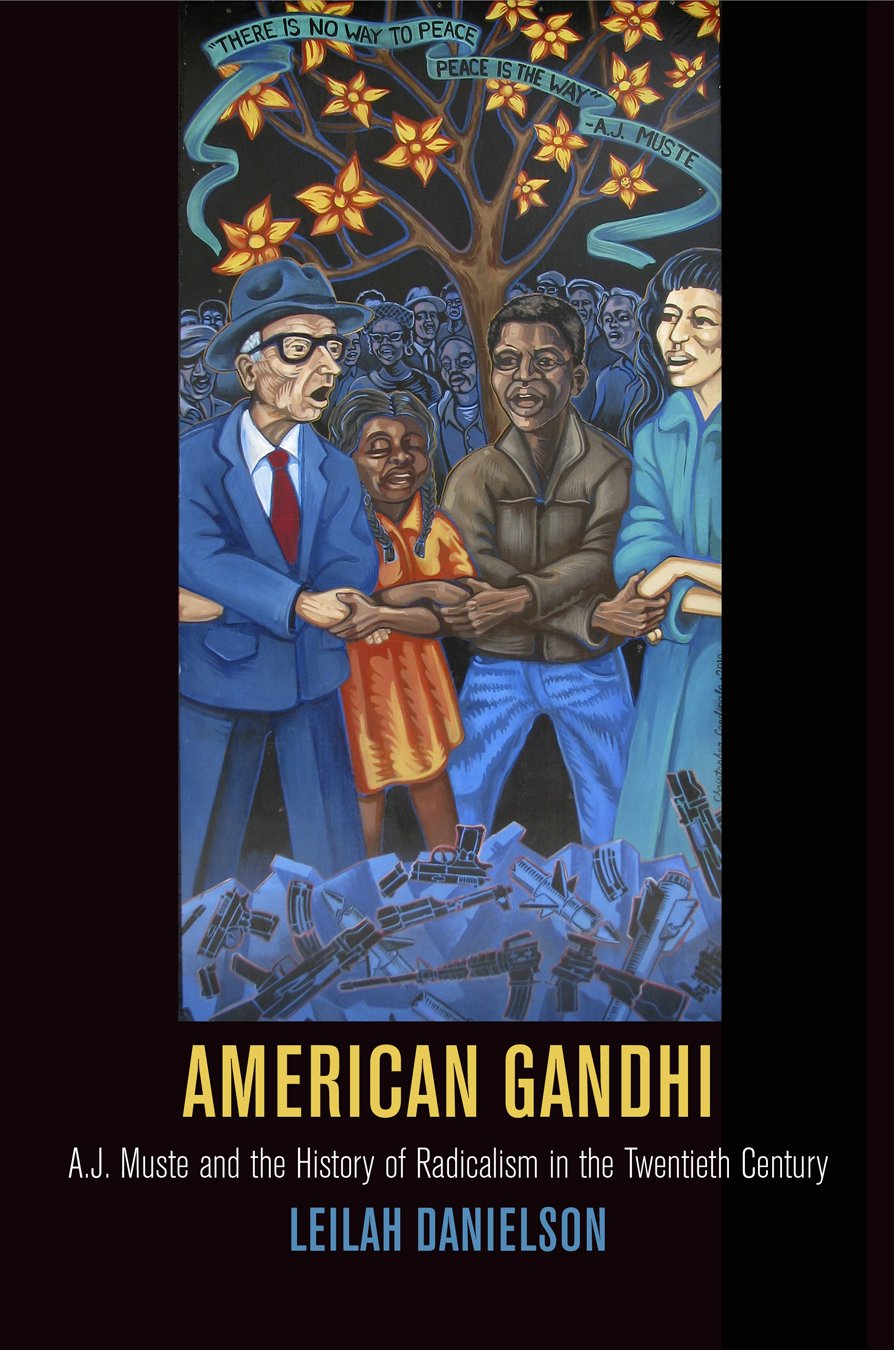

Dear reader: This is part seven of our seven-part roundtable on Leilah Danielson’s remarkable book, American Gandhi: A.J. Muste and the History of Radicalism in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014). For part one, by me, go here. For two, by Tim Lacy, go here. For three, by Lilian Calles Barger, go here. For four, by Wes Bishop, go here. For five, by Janine Giordano Drake, go here. And for part six, by Raymond Haberski, Jr., go here. Today’s final entry is by Danielson herself, who responds to the roundtable. (Note: not all of the entries had been written when Leilah wrote this.) Leilah is a professor of history at Northern Arizona University. In addition to authoring American Gandhi, she is co-editor (with Doug Rossinow and Marian Mollin) of a forthcoming anthology entitled The Religious Left in Modern America: Doorkeepers of a Radical Faith, a collection of exciting new scholarship that provides comprehensive coverage of the broad sweep of 20th-century religious activism on the American left. Her current project is an intellectual and cultural history of the workers’ education movement of the interwar years. It has truly been a pleasure organizing this roundtable for such a fantastic book! Andrew H.

Many, many thanks to the reviewers for offering such generous and insightful comments on American Gandhi. I am gratified that they recognized my ambition to write not simply a biography of A.J. Muste, but an intellectual and cultural-social history of the modern left. They also observe that the book serves, as Wesley Bishop puts it, “as a meditation on leftist politics.” Or, as Andrew Hartman puts it, Muste’s “life as an activist demonstrates the ways in which the left-liberal side of the American political spectrum is rife with contradictions (and promise, but only if these contradictions can be overcome).” Or as Tim Lacy puts it, Muste serves as a “powerful exemplar and cautionary tale for today’s leftists.” Interestingly, I never intended the book to serve as a commentary on contemporary progressive politics, but precisely because Muste was at the center of the most important social movements in modern U.S. history, he offers us an opportunity to reflect upon the question of “what is to be done?” Before continuing with this train of thought, I’d like to respond to some of the other points raised by these reviews.

If Americans remember Muste at all, it is as a pacifist and Christian, yet Andrew Hartman’s review rightly emphasizes his contributions to the industrial labor movement and Marxist thought during the 1920s and 1930s. As Andrew points out, Muste was a revolutionary idealist, but he was also a Jamesian pragmatist who believed that the truth of an idea had to be tested in action, experience, and community. This approach, as Andrew notes, allowed him to bridge the “historical divide” between the world of pacifism “to the labor movement, which was largely immigrant and working-class.” It also accounts for his innovations in Marxist theory that anticipated the work of V.F. Calverton and Sidney Hook, who usually get all the credit for their efforts to “Americanize Marxism by fusing it with pragmatism.” [i] Indeed, it was no accident that Calverton and Hook, both of whom had resisted joining the Communist Party and the Socialist Party, would be drawn into Muste’s movement of militant unionists in the late 1920s and early 1930s. As head of the Amalgamated Textile Workers of America (1919-1921), then as head of Brookwood Labor College (1921-1933), and finally as director of the Conference of Progressive Labor Action (1929-1933), which became the American Workers Party in 1934, Muste had evolved a humanistic Marxism that emphasized praxis over dogma and solidarity over sectarianism – and which pioneered the cultural front (see esp. chapters 3 and 4 of American Gandhi). His 1931 review of Hook’s Toward an Understanding of Karl Marx, reveals his pragmatism, as well as his characteristic wit. “It is obviously possible on this interpretation to accept the validity and permanent importance of Marx’s method without feeling bound to use him as a Talmud and Bible,” Muste commented approvingly. At any rate, “If his interpretation of Marx is not the correct one, then it should be.” [ii]

Eventually, Marxism – or, more precisely, Marxist-Leninism, which Muste adopted in 1934-36 – became for him a Talmud and Bible and he felt compelled to discard it. As he recalled, “I was brought up hard against the realization that by that very pragmatic test which I had chosen the method [of Marxist-Leninism] did not produce the desired results.” [iii] Andrew interprets his subsequent return to pacifism and adoption of Gandhian nonviolence as part of an ongoing quest to find a “radical vision that connects with Americans,” and suggests that it was one of Muste’s Achilles heels, so to speak. He may have had an Achilles heel, more along the lines of what Andrew describes as his “sectarian” tendencies, but I would push against the idea that it had anything to do with a desire to connect with Americans. Like any good organizer, Muste insisted that any effort to transform society had to begin with an understanding of its political economy and culture, not to reinforce its prejudices, but to develop appropriate strategies for changing it. Like any good revolutionary, he believed that it was possible to build a new society based upon justice and equality, hence his fondness for Proverb 29:18, quoted by Lilian Calles Barger, “Without vision, the people perish.” Perhaps foolishly, he held out hope (at least until the Vietnam War) that Americans could somehow be convinced to repudiate their long tradition of race, empire, and war, but it’s hard to imagine a socially transformative politics without hope.

There was a pragmatic element to Muste’s adoption of Gandhian nonviolence. On a personal level, as I note above, it allowed him to stay on the left without compromising his ethical and religious principles. On a political level, its confrontational and collective form of protest promised to revitalize a pacifist tradition that seemed too individualistic and ineffectual.

And yet he was not so pragmatic that he had no center; he drew the line even when it meant losing influence over his fellow Americans. As Andrew points out, it was no coincidence that Muste became a Trotskyist at the same time that the labor movement, which he had done so much to build, made what Nelson Lichtenstein calls a “Faustian bargain” with the Democratic Party. [iv] Lilian Calles Barger’s phrase “revolutionary social democratic idealism” is provocative here. Muste eschewed social democracy; like others on the far left, he viewed the parliamentary process as a weak mechanism for radical social change and looked to direct action. This is what links his pre-war career to his post-war career, even as he charted a new form of Christian radicalism to challenge U.S. global power, race, and militarism.

As Lilian points out, social Christianity had a profound influence on American reform and radicalism in the 20th century, yet it has often been neglected by historians of the left. She suggests, I think correctly, that this has to do with the fact that it “came under intense criticism in Depression-era politics,” charged by Niebuhrian realists “with being an idealistic and politically unworkable blend of religious ethics at odds with the realities of exercising political power.” Indeed, historians have too often allowed Niebuhr to shape the narrative of social Christianity as one of innocence into maturity (not unlike the scholarship on fellow travelers and the Popular Front). Attention to Muste shows that the religious left persisted and evolved new, more dynamic forms of dissent such as revolutionary nonviolence, a project that involved drawing from Gandhi’s ideas and merging them with Marxist-Leninism, Christianity, and western-style pacifism.

Another possible reason for the declining attention to religion in scholarship on U.S. social movements has been the shift in the historiography of the Civil Rights Movement away from an earlier tendency to bifurcate the movement between its “good” years of Christian nonviolence and its presumably “bad” years of Black Power. Certainly attention to the nonreligious and more nationalist forms of black protest was an important corrective, one that I contributed to in a small way in my 2004 article on James Farmer, CORE, and Black Power. [v] But this new historiographical paradigm has perhaps taken its materialism too far, in the process deemphasizing the salience of Christianity for many activists, even during the Black Power era.

When Muste embraced Gandhian nonviolence as a method of social transformation in the 1940s, he hoped it would reenergize the left against what he saw as its cooption by the Democratic Party and the warfare state. He also sought to create a “true church” that would prophetically and unequivocally oppose race, nation, and war. This idea drew from the ecumenical movement, a fact that Tim Lacy rightly points out could have received more attention in American Gandhi. As Michael Thompson explains in his excellent new book, For God and Globe

, the Oxford Conference of 1937 called upon Christians “to engage in redemptive action and witness” through building up a supranational and supra-racial universal church, that “would finally be, at the end of history, united in Christ.” [vi] Muste took these ideas in a more radical direction than other ecumenical Protestants and hoped to persuade others to do the same through his continued involvement in the World Council of Churches. Tim also refers to the possible influence of non-Protestant thinkers, including Dorothy Day of the Catholic Worker Movement; in the interest of shortening an already long book, I did in fact cut a section that described Muste’s engagement with the ideas of Jacques Maritain, Nicolas Berdyaev, among others, as well as the Jewish Martin Buber. Both of these lines of inquiry deserve more attention from scholars.

With the atomic bomb and the Cold War, Muste’s politics increasingly took on a prophetic dimension in the utopian hope that radical pacifists’ dramatic acts of civil disobedience would somehow awake Americans to their complicity in militarism and war. In the book, I resisted the temptation to make this explicit because I recognized that he continued to seek the realization of his ideals in community through his support for the Civil Rights Movement and through his herculean efforts to build a transnational movement against nuclear weapons and, especially, the movement against the war in Vietnam.

Here, then, I would like to return to question of whether Muste can serve as a “cautionary tale” for today’s leftists, as the reviewers’ suggest. In the book, I suggest that Muste was a prophet and a pragmatist, and that the tension between these two poles provides a key to understanding the history of the U.S. left in the 20th

century. We might also posit it as idealism vs. realism, individualism vs. community, sectarianism vs. coalition-building, theory vs. action, and so on. This tension was mostly enabling through the 1940s, but in the postwar era the prophetic impulse predominated and perhaps, as Tim suggests, “worked against [Muste’s] desire for solidarity.” He became “an Isaiah, a voice crying out in the wilderness.”

On the other hand, we might argue that Muste’s prophetic stance made sense in the context of the 1930s through the 1960s when liberalism was more or less dominant. His outsider stance pushed up against the liberal establishment, forcing it to confront the limitations of its creed on race and empire. But, for a long time now, liberalism has occupied a rearguard position and a resurgent conservatism has set the terms of political discourse. Meanwhile, the lives of working people have become ever more precarious and desperate, and policies that once seemed moderate or centrist – such Social Security, public education, and collective bargaining – appear liberal and even radical. Perhaps both an insider and outsider approach is more appropriate at a time in which we’ve lost the community to the individual. In other words, until we recover notions of solidarity and security, individual prophetic action may not be enough to turn course.

[i] Michael Denning, The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century (London: Verso, 1997), 425.

[ii] Leilah Danielson, American Gandhi: A.J. Muste and the History of Radicalism in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), 159.

[iii] Ibid., 198

[iv] Nelson Lichtenstein, Walter Reuther: The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit (Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 175

[v] “The ‘Two-ness’ of the Movement: James Farmer, Nonviolence, and Black Nationalism.” Peace and Change: A Journal of Peace Research 29, no. 3&4 (July 2004): 430-53

[vi] Michael Thompson, For God and Globe: Christian Internationalism in the United States between the Great War and the Cold War (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015): 100, 122.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this response—for engaging our roundtable. It’s pretty clear we all enjoyed the book. Well done! Does your next project deal with a Muste-related topic? Or are you moving to something far removed? I can imagine you need a healthy break from him after such a detailed, in-depth treatment. – TL

PS: You an always count on Catholic-related questions from me. Day is a personal hero, but several others have figuring into my professional research and writing.

You guessed right, Tim, I was pretty burned out after writing American Gandhi. There were still more directions I could have taken the book, and I hope that other scholars will continue to research Muste’s historical significance, particularly to ecumenical Protestantism, the international peace movement, and the 1960s.

Over the past year, I have been enjoying a very fruitful collaboration with Marian Mollin and Doug Rossinow on an edited volume entitled The Religious Left in Modern America: Doorkeepers of a Radical Faith (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). Shameless plug: the essays are fantastic and together demonstrate that a history of the modern left is incomplete without religion.

In the long term, I want to build upon the research I did for American Gandhi on the workers’ education movement of the 1920s and 1930s.

Thanks again for all of your support! I look forward to future collaborations.