As a student of the historical and present-day phenomena called, variously, ‘anti-intellectualism’, ‘unreason’, ‘ignorance’, or ‘thoughtlessness’, I’ll read just about anything covering those topics. I do this for fun, but I’ve also had the good fortune, recently, to teach a bit on them too. That teaching tells me that people “like” talking about these issues. At the very least the word cloud of problems that describe these phenomena beg for dialogue and reflection.

As a student of the historical and present-day phenomena called, variously, ‘anti-intellectualism’, ‘unreason’, ‘ignorance’, or ‘thoughtlessness’, I’ll read just about anything covering those topics. I do this for fun, but I’ve also had the good fortune, recently, to teach a bit on them too. That teaching tells me that people “like” talking about these issues. At the very least the word cloud of problems that describe these phenomena beg for dialogue and reflection.

A new publication, Kurt Andersen’s Fantasyland, seeks entry into the discussion. Released just last month, my regular libraries have not yet acquired this Penguin Random House publication.

Thankfully Andersen’s pre-publication marketing plan involved a long article in his home publication, The Atlantic. Titled “How America Went Haywire,” the essay succeeds in whetting the appetite for Andersen’s longer analysis. Please read it. Rather than summarize it here, I want to focus on some preliminary criticism. Let there be no doubt that the article leaves room for questions and doubts about Andersen’s analysis. What follows is likely addressed in the book, but I want to relay what I’ll be thinking about when I proceed with my reading of Fantasyland

.

To be fair, and nice, let me provide three promotional quotes—likely back cover stuff.

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

“With this rousing book, [Kurt] Andersen proves to be the kind of clear-eyed critic an anxious country needs in the midst of a national crisis.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“This is a blockbuster of a book. Kurt Andersen is a dazzling writer and a perceptive student of the many layers of American life. Take a deep breath and dive in.”—Tom Brokaw

“This is an important book—the indispensable book—for understanding America in the age of Trump. It’s an eye-opening history filled with brilliant insights, a saga of how we were always susceptible to fantasy, from the Puritan fanatics to the talk-radio and Internet wackos who mix show business, hucksterism, and conspiracy theories.”—Walter Isaacson

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

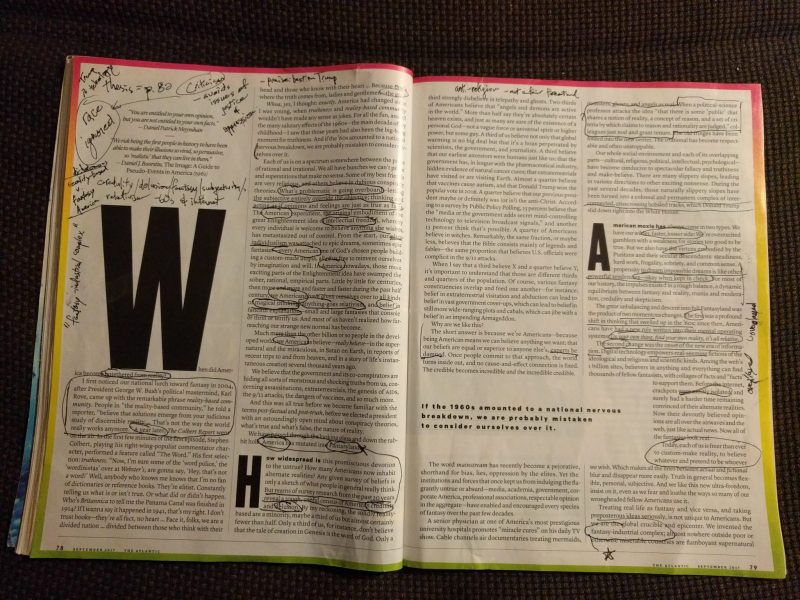

And, in cases you’re wondering how closely I read the essay, let me show you a picture of my annotations, just on the opening pages.

So, with nods of respect given, and based on the article alone, I’m going to wade into several complaints.

First, race seems to be ignored—or is at the very least under-explored. Although the article makes mention of race (“white Christians” and “white Americans,” p. 88; the question of Obama’s birth country, p. 90), the article neglects to address, in head-on fashion, the question of how race is related to questions of reality and fantasy, or individualism and religion, takes a back seat. There is no addressing the question of anti-intellectualism without a deep analysis of the structures of reason, emotion, and sensibility.

Second, it makes too much of the reality-fantasy distinction in American thought life. Even though I appreciated Andersen’s invocation of the “fantasy-industrial complex” (p. 79), I think, in his hands, it hinges too much on religion (p. 87-89), and thereby underplays the good that religion brings to the table in America. Religion in American history has helped, at crucial points, to forward the cause of justice and to fight against oppression. But Andersen links religion to an excessive tendency to believe in conspiracy theories (p. 87). Despite this complaint, I believe Andersen is right to argue that “the reality-based left more or less won” in the late 1960s, and that the right gave up on reality in the 1990s. This culminated with Karl Rove’s infamous quote, circa 2003, that the “judicious study of discernible reality [is]…not the way the world really works anymore.” Even so, the hard reality-fantasy distinction underplays the ad hoc, contingent constructions with which we all deal, no matter our political leanings.

Third, and related to #2, the article’s Trumpian teleology distorts its view of the history of anti-intellectualism, ignorance, and thoughtlessness. This is a growing complaint, fed by a readings of numerous articles that began late in 2015 and built all through 2016. Hardly an analysis of Trump, Trumpism, and his voters passes by that isn’t littered with terms and descriptors like idiocy, stupidity, cognitive dissonance, ignorance, false consciousness, fools, ideology, motivated reasoning, post-truth, post-fact, the Dunning-Kruger Effect, backfire effect, etc. Trump’s voters have been psychoanalyzed more than Oedipus, Anna Freud, Woody Allen, and Luther.

I don’t disagree with Andersen’s analysis of Trump as a P.T. Barnum-esque figure—creating a show that some buy as reality. But Trump is the reflection of several long-running trends in American history, a product of not only our intellectual deficits, but also some of our assets. Traits of the electorate that elected Trump also elected Obama, Bush 43, Clinton, and Bush 41. Focusing too much on Trump elides a host of factors that have brought us to this unique moment in our history.

Once I acquire the book I’m sure I’ll have more complaints, and some praise. But I have a feeling, preliminarily, that I won’t be comfortable recommending the book as a viable contribution to the historiography. But like the realities in which we all live, this judgment is contingent. I’ve been known to change my mind. – TL

0