Editor's Note

This is the fourth of six guest posts from Anthony Chaney that are appearing on the Blog every other Saturday. The earlier posts in this series can be found here, here, and here — Ben Alpers.

Scenes of Houston, covered by floodwaters, resonated with another image on my mind this week: James Dean, drenched in oil.

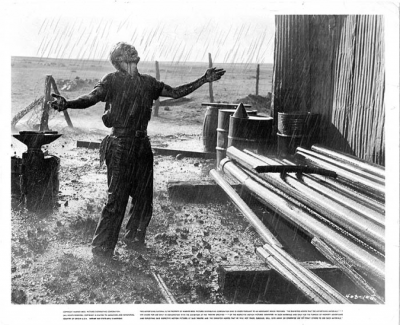

Those who’ve seen the movie Giant surely know the image I mean. I haven’t seen that movie for decades but the scene in question is a memorable one. The character Jett Rink, played by Dean–working class kid, shyly and awkwardly pining for the wife of the rich rancher who employs him–strikes a gusher on his own little stake of land. He rushes over to the wife with the news of his good fortune, still covered in the oil that he knows will make him–well, filthy rich. As I remember it, the character is transformed, and all that was hidden inside–all the frustrated desire and ambition, the sting of poverty and class shame–comes out in a sort of gloating dance of joy. From the speech and body language of a character we have sympathized with, we get a glimpse of a monster.

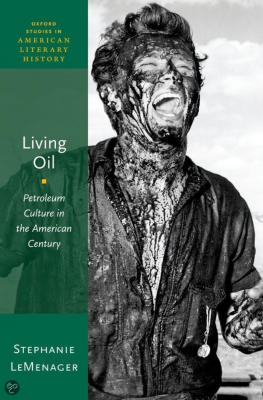

So transformed is Dean’s face that I didn’t recognize it at first in the still from that scene on the cover of Stephanie LeMenager’s book, Living Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century (Oxford UP), out in paperback last year. LeMenager is the Moore Distinguished Professor in English and American Literature at the University of Oregon and the co-founder of Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities. I had the opportunity to meet her this past summer and to hear her speak about her work at a National Endowment of the Humanities summer institute called City/Nature: Urban Environmental Humanities. The institute gathered a number of humanists from a variety of disciplines to share and explore how their research has focused on environmental issues and to understand where the emerging field of the environmental humanities stands at present, especially in regard to thinking about the living city. We read and heard from a number of guests, leading voices in this field, and LeMenager was one of them.

We are all Houstonians this week, hearing from family and friends who live in southeast Texas and witnessing the plight of many other Americans who have suddenly lost the ability to meet the most basic needs of life. We are all Houstonians and have been for a long time, at least since the Spindletop strike of 1901, which ushered in the Texas Oil Boom and gave birth to Chevron, Texaco, and Gulf. Those conditions are what LeMenager calls “conventional oil,” the relatively easy-to-extract, abundant oil that shaped American modernity. That period is over, as we all must know, and the age of “Tough Oil” is upon us, and as bad as conventional oil was for our environments and our psyches, Tough Oil is worse. Made possible by the new practices of deepwater drilling and fracking, Tough Oil is “not the same resource,” LeMenager insists. All its costs are higher, ecological, social, and biological.

Climate change and the phenomena of petroleum culture overwhelms us with its geo-atmospheric and transnational scale. LeMenager’s critical practice, which she describes as “regional consciousness,” is an effort to overcome this difficulty. She reads regions, so to speak–the fictions and non-fictions, the performances and testimonies of the sites and capitols of our energy system, places such as Houston and the Gulf Coast. The Houston area has long been “deeply entangled with modernity’s most risky objects,” all the violent apparatus of oil extraction, refinement, and transport. More recently, it has pioneered the “ultradeep” experiments in Tough Oil extraction. The BP blowout of 2010 was one early disaster in that extraction, a “humiliation of modernity” that “localized a plethora of visible data.” The superstorm Harvey is doing the same thing today.

Drawing, too, on the practices of cultural studies, LeMenager addresses the “structures of feeling” involved in our attachment to oil. She employs the term “petromelancholia” to describe and explore our grief over the passing of conventional oil and thus of the end of American modernity as we’ve understood it to be. Because this grief is “unresolved,” it’s shot through with “contradictory emotions.” Our energy system is “charismatic” but “profoundly unsustainable.” Our attachment involves both “injury and pleasure.”

And why wouldn’t we be sad and confused about this? Petroleum culture shaped our built environments no less than as it has our imaginings of what it is to be alive. Each of us has our own ton of unorganized plastic floating out in the ocean to mark the significance of our vitality. Cheap energy shapes the structural violence of today’s national and corporate powers; relatively recently and on a smaller scale, planes and cars have become weaponized as the politics of climate change intensify. We live oil, as LeMenager encapsulates in her book’s title. Even if we were to cease burning fossil fuels immediately, extracting oil’s remnants from our semiotic stock would be a task more daunting still. Live fast and leave a beautiful corpse! James Dean embodied that idea in life and on film, aided by an assortment of automotive and petrochemical products, including film itself.

Petromelancholia and “carbon masculinity,” another of LeMenager’s terms, were in my mind while I sat in a theater this summer and watched the movie Baby Driver. The protagonist is a baby-faced young man who drives the getaway car for a local crime boss. The film is part of a long tradition of movies that feature car-chase set pieces, that are about car racing, or that focus solely on people driving cars recklessly and fast. What makes Baby Driver different is that every high-speed turn, every spinning skid, every crash and pursuing gunshot is synchronized with a musical moment in the soundtrack. There’s a cultural provenance, too, in the film’s gendered tropes. Cars and trucks are boys’ toys, as are rockets and guns. What is it about fast cars and guns that appeals to the masculine imagination? That these are tools that encourage the illusion of reaching an objective at lightning speed? That these machines built to enhance control must be used to put that control at ever-higher risk? (See my last post about paradox.)

Petromelancholia and “carbon masculinity,” another of LeMenager’s terms, were in my mind while I sat in a theater this summer and watched the movie Baby Driver. The protagonist is a baby-faced young man who drives the getaway car for a local crime boss. The film is part of a long tradition of movies that feature car-chase set pieces, that are about car racing, or that focus solely on people driving cars recklessly and fast. What makes Baby Driver different is that every high-speed turn, every spinning skid, every crash and pursuing gunshot is synchronized with a musical moment in the soundtrack. There’s a cultural provenance, too, in the film’s gendered tropes. Cars and trucks are boys’ toys, as are rockets and guns. What is it about fast cars and guns that appeals to the masculine imagination? That these are tools that encourage the illusion of reaching an objective at lightning speed? That these machines built to enhance control must be used to put that control at ever-higher risk? (See my last post about paradox.)

By the time I saw the movie, I’d met LeMenager and heard her presentation, but I hadn’t yet read her chapter on petromelancholia or understood her argument in its depth. Nevertheless, as I watched the film, even my superficial grasp of her critique made me interrogate the movie more deeply than its makers likely intended. Why must these cars be driven so madly? Why must they be jerked around this way and that? This nagging insistence on moving bodies quickly through space portrayed not an adult’s mindful composure but a baby’s restlessness and anxiety. The Monkey Mind was at the wheel. The line Flannery O’Connor gave the preacher Hazel Motes in her novel Wise Blood became relevant: “Where you come from is gone, where you thought you were going to was never there, and where you are is no good unless you can get away from it.”

These were searing, chastening insights. They interfered not at all with my deep enjoyment of Baby Driver, as I’m sure LeMenager would understand.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Anthony, thanks so much for this wonderful essay. Confession: I had to scroll quickly past the Baby Driver section, lest I be exposed to spoilers — though I did learn, just from your first sentence in that section, that I had somehow confused Baby Driver with the recent animated film The Boss Baby, and I could not for the life of me figure out why people I know were raving about Baby Driver being a great film.

On “carbon masculinity” and how that manifests in our current political moment, I was reminded of the practice of “rolling coal” where diesel pickup-truck drivers install a mod that overfuels the engine at the push of a button and sends billows of black smoke out the exhaust pipes to becloud the drivers behind. Coal-rollers post YouTube videos of their exploits, usually aimed at Prius drivers, Subaru drivers, or just people w/ politically “liberal” bumper stickers. I got coal-rolled once while driving a convertible with the top down, though I have no bumper-stickers or other markers of being a “liberal.” Maybe just being a woman behind the wheel, driving by myself? I don’t know. It was a decidedly unpleasant experience. The whole point of rolling coal, as far as I can tell, is to not only glory in wastefulness to make a political statement but also show that the potent polluter has the power to direct the consequences of that waste upon others.

That said, I must confess that “carbon masculinity” can be a weakness for some of us tomboy/gender-bending types as well — I used to drive an off-road truck built like a tank, and I *loved* it. Gas mileage was abysmal, vehicle was ridiculously oversized and over powerful for the purposes of suburban life (but could off-road like a beast in the soft sand of North Padre Island). It had over 170,000 miles on it when I wrecked it, or I would probably be driving it still. I do love a big truck — as long as I’m the one behind the wheel.

I draw the line at TruckNutz, though.

L.D., All week I was trying to remember the example Stephanie LeMenager used to illustrate the term “carbon masculinity.” It was coal rolling. Thank you for supplying that answer! And thanks for offering another example of how deep the pleasure side of the pleasure/injury dynamic is in oil attachment, no matter what our genders are.

Not sure I would describe Baby Driver as great, but I did find it to be great fun. I’m not sure it’s the sort of movie that can be spoiled by information … but I don’t think there are any spoilers in the BD paragraph.

This is a wonderful essay, Anthony–and thank you for mentioning our conversation and *Living Oil.* I do need to attribute the term “carbon masculinity” to Stacy Alaimo, however. You’ll find it in her book *Exposed,* whose cover returns our thoughts again, to Houston.

Another great post Anthony. I’ve been genuinely enjoying your work here at the blog. First, I know I need to get my hands on a copy of Stephanie LeMenager’s book once it arrives. It sounds fascinating. Second, I’m getting ready to discuss the Teapot Dome Scandal on Thursday in a 1920s class I teach, and I was thinking about the terrifying echoing of the Giant scene in P.T. Anderson’s There Will Be Blood. I can’t get Daniel Day Lewis/Daniel Plainview’s maniacal grin while covered in the gush of oil out of my head. (It’s like oil porn/snuff film or something.) I was thinking I’d use the meme-inspiring “milkshake” scene from the film in connection with Albert Fall’s “milkshake” testimony before the Senate. There’s an oil masculinity-as-political chicanery idea rolling around in there somewhere that maybe reinforces that ambivalence–(“petromelancholia–love that)–LeMenager conceptualizes, this time when it shows up in P.T. Anderson’s film–appearing in the age of “tough oil,” but depicting the age of “conventional oil.” Extraction by subterranean means from an adjacent space: now I’m wondering what to make of it, whether and how the image prefigures the “tough oil” age in some way.

Thank you for reading and responding, Peter. The *There Will Be Blood* scene definitely came to mind when I was thinking about the post. As you suggest, it’s a film about conventional oil made in a tough oil era. *Giant,* in contrast, is not only about conventional oil, but is an artifact of conventional oil. I wasn’t aware of the “milkshake speech” in connection to Teapot Dome and have never read the Sinclair novel, though a quick internet search would have supplied that info. Now the scene in that movie makes much more sense. I’m gathering that the milkshake line was not in the novel but that PT Anderson brought it in via the Fall speech.

In any case, what a benign metaphor for so violent and ugly a process. I think I remember Amitav Ghosh writing about how oil has been difficult to aestheticize because of the unrelenting ugliness of it and of the workings of the industry. (My grandfather worked oil rigs in Texas and Oklahoma as a young man. He took some pride in that work but also got out of it as soon as he could.)

Not sure I made this clear, but LeMenager’s book was first published in 2014—the paperback version I have came out in 2015.

Now I plan to buy that book. Thank you for clearing that up. My mistake. As for Fall and milkshakes, I’ve not read Sinclair’s Oil! so I’d need to dig into that. It could be in there, seeing how Fall testified in 1922 and that novel came out in 1927 (there’s an internet factoid.) for some reason my historian brain thinks it would somehow be better if it weren’t in the novel if that makes sense.