In part one and part two in this series of posts, I relayed Nietzsche’s basic arguments in “Uses and Abuses.” Now it makes sense of shift gears a bit, considering where and how the rubber hits the road. There are risks here, especially the sin of vanity. In Nietzschean fashion, any critique risks privileging the present in the wrong way, reinforcing widely held opinions of our day or the trends common to this or that academic industry. Yet it would be strange not to carry the philosopher’s insights into the present. At some risk then, this final installment concerns the problem of nationalism/monumentalism in Nietzsche’s essay, the question of heroism and/or elitism, the rigors teaching in the academic “industry,” and finally, whether Nietzsche’s claim about an “excess of history” holds true for the United States in the present day.

It seems odd and even fascinating for Nietzsche to have lamented the lack of German unity on the heels of German unification (The essay appeared in 1874). But the nearness of unification only reinforced Nietzsche’s point. Political unity meant very little without cultural and intellectual unity. The nationalism of “Uses and Abuses” troubles the modern reader nonetheless. Bismarck looks mighty good to us, knowing as we do the terrifying path of nationalisms in the 20th century: fascism, Nazism, and so on. Reading Nietzsche right now, I find it interesting how much forgetting and selective memory accompanies our current “America First” moment. The president of the United States is low-hanging fruit nowadays. Discussions of the head of state can become tiresome, but any account of nationalism/monumentalism in our current moment should deal with the man. The idea “Make America Great Again” is monumentalism with a vengeance, a monument to some terrifying white American id, conjured up as one man’s narcissistic projection out in the world and driven by deep feelings of inadequacy, a monumentalism so pure it lacked for monuments—at least for a while.

Tragically, in the nick of time some “Confederates in the Attic” helped this “America First” movement rustle some up. The results were revealing of course, and what Nietzsche called the deceptions “by means of analogy” in monumental historical thinking colossal. So in a strange way, rather than a lack, an excess of history in the form of monumental historical consciousness could be to blame here. When Nietzsche lamented the “excess of history” he meant both an excess of much of what might be called “the historical spirit”—obsession with past greatness—and the insatiable hunger for historical details. Both can create problems. Both can damage a culture. In their excessive moods, the monumentalists secretly hate greatness and never want it to appear again, because nothing can surpass the greatness of the past. In a related way, the narcissist actually hates himself and loves instead the projection of himself in the world. Recent events suggest a worrisome equation: excessive monumentalism plus narcissism equals nihilism. It fetishizes the worst monumentalist logic. This partly explains the weird uptick in obsession with Confederate heroism again. When it’s bad, nationalism can be scary in the first place, but only a thoroughly nihilistic nationalism would defend monuments crafted in rebellion against itself. Nor should it surprise us that a nihilistic monumentalist would attack probably the only widely agreed upon examples of human excellence in our democratic cultural life, namely professional athletes. Nietzsche’s Greeks wouldn’t have done that.

In a bizarre world like this, Nietzsche’s consistent attacks on “objectivity” in “Uses and Abuses” could seem overwrought or worse, dangerous. We might excuse his frustration because of his own time and place, when a rage for statistical thinking and positivism filtered through academic communities in Europe. Nietzsche attacked objectivity because he worried whether it had become what might be called “scientism,” a worship of the purely factual, a high church of detachment in and for itself. It wasn’t the method necessarily, but the motives behind the methods. He thought objectivity-qua-objectivity a poor substitute for justice. He never meant we shouldn’t be rigorous or that facts didn’t matter, only that scientific rigor in and for itself could become fetish of a kind. We forgot why we did history in the first place. Admittedly, it’s a perilous moment right now. Questioning the realm of fact requires careful consideration of what that entails. We live amidst what, in The Plot Against America, a dystopian novel about the earlier America First movement, Philip Roth’s narrator calls “the terror of the unforeseen.” Counsels of patience for objective work don’t sound so bad right now because they appear to provide clearer standards for proof. Yet it should be evident from Nietzsche’s example that a few more thousand rigorously sourced essays, books and articles on U.S. history won’t change the minds of anyone who voted to “Make America Great Again.” Maybe someone should craft a better monumentalism instead. To be honest, I’m not sure how to go about that. This problem of mine is no doubt a symptom of what Nietzsche called a “weak personality” among moderns.

Sometimes Nietzsche’s description of a stagnant, dead intellectual life in 19th century Germany perplexes me. Looking back, it seemed pretty spectacular, a generation or so removed from the likes of Hegel, Schiller, Fichte, or Herder, and on the cusp of Weber, Husserl or Freud. My little democratic heart also beats too insistently to buy wholesale Nietzsche’s apparent obsession for greatness among historical figures and events. The bar seems impossibly high, or set in too traditional a place, in the world of something like Thomas Carlyle’s On Heroes, Hero Worship and the Heroic in History (1841). Nietzsche set a mean trap; he would probably say my democratic, antiquarian heart is precisely the problem. I can’t easily distinguish the unimportant from the important any longer. But we get howlers like these in the essay: “Only in three respects does it seem to me that that masses are deserving of notice: first, as faded copies of great men printed on poor paper with wornout plates; second, as resistance to the great; and finally, as tools of the great. With regard to everything else, they can go to the devil and statistics!”[1] To be entirely fair, a statement like this requires context. Nietzsche referred here to those histories concerning the masses-as-abstraction, as an object for statistical analysis and prediction, along the lines of Henry Thomas Buckle’s ridiculous History of Civilization in England (1864). At its best, this sounds like something Dostoyevsky might have said about 19th century Russian nihilists and their bizarre formulations: “to the devil and statistics!” At its worst, Nietzsche seemed to ignore the soul of Dostoyevsky’s deeper insight, that suffering among the presumably obscure has spiritual value. To draw from Crime and Punishment, for every Raskolnikov who thinks he knows something about greatness, there is a Sonya to set him straight.

Closer to my own life, I often think of a character from a novel that has merited renewed consideration recently, namely John Williams’ Stoner, the story of an obscure academic who gives up the inner life of the farm for the inner life of books, the classroom and the mind. William Stoner publishes one book, but he insists that the life of the mind mean something deeper than that, even in the academy, as its bureaucratic features and oppressive social world chew him up and spit him out. He dies in obscurity, but it’s hard not to see in his struggle something beautiful even if not entirely redeeming. He expressed himself, he put something out in the world, and he believed truly and completely in the ideas he taught his students. So maybe that kind of failure is an idea with a whole lot of promise.[2]

Nietzsche’s concerns over the academic industry make some sense to me, particularly as someone who teaches undergraduates exclusively. While I think it necessary to introduce students to the conversation in our own fields of study, that conversation can become a barrier to wonder or joy when it comes to ideas if not done right. I’m curious how others among us deal with this problem. I’m still figuring it out. I teach a Senior Seminar meant to prepare students for the job market, some for graduate schools (perilous, that). A consistent refrain I hear from the group is something I mentioned last time out, that they don’t think, given how much has already been written about what interests them, they can possibly contribute anything new or meaningful. To borrow from Lenin who borrowed from Chernyshevsky who probably borrowed it from someone else, “What is to be done?” Should students find something very small or ignored, tinkering for themselves with an ultimate end of doing little else than contributing their little part, dedicating countless hours of life to a product meant to occupy a designated corner in the vast storehouse of knowledge about some subject? (That doesn’t seem too bad in a sped-up world.) But what if one of my students has a genuine passion for a major event like a revolution, a powerful idea like goodness or innocence, or a thoroughly sifted-over life?

My own small solution has been to insist students read what historians call “primary” texts before ever worrying about what scholars have said in “secondary” sources. If, after that, their interest piqued, further study leads down more idiosyncratic or esoteric paths while holding their interest, then so be it. Seeing how dire the academic job market is for the traditional liberal arts, they had better develop a passion for something before diving into the second layers. Another tactic of mine has been to give them an impossibly big question over an unreasonably short period of time in venues like exams. I have students synthesize enormous amounts of material over long periods of time (several decades) to force them, against their cautious natures, to make serious judgments for themselves about the important and the unimportant. Then we go from there. For example, I taught a course this past spring called “The U.S. Viewed from Abroad” which deals primarily with European travelers and visitors’ accounts of the U.S., from Crevecoeur and Tocqueville to Dickens, Marx, Henry James, Adorno, Arendt, and Simone de Beauvoir among others (the first decades of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th). One of the questions on my final is totally perverse:

Henry James, when he visited the U.S. in the early 20th century, wrote that for travelers, “America is a bad country to be stupid in.” Explain what he means.

That question is unfair and unfocused, but that’s the point. It forces a person to define what that statement means and then apply it across a long period of time, accounting for historical change, deciding when, to whom, and where it applies, what’s important to the insight and why, etc. In any case, very few of the students I teach will ultimately earn PhDs, so teaching them about how to be free, how to create and craft a world for themselves and those around them comes before teaching them about how to get enough to eat, to deal with problems of biological necessity in an ever-changing economic market. I don’t mean this in a hectoring way because I’m in no position to hector anyone or to be moralistic about this. I’m more or less curious about how people in different places handle that constant question one gets from parents, about just what their child will do with a history or a philosophy degree. I want to say, “folks, I’m trying to teach your precious child how to avoid becoming an asshole.” I don’t guess that would go over all that well.

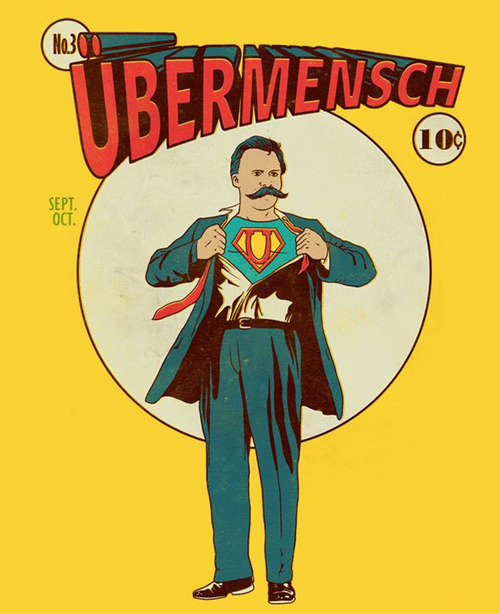

So what about this excess of history business? This one is interesting, because it’s commonplace now for historians and even those in public life to lament how little people know about their own history. As long as history has been a formal subject in academic life, pundits and critics have complained about public ignorance. I wonder if this isn’t misplaced. I would argue we still suffer from an excess of history. The difference is, among the many young people, the excess has often moved into the realm of fantasy. Makers of encyclopedic wikis of Marvel Comic characters, for example, compile the backgrounds of purely fictional characters with obsessive detail, maniacally tracking chains of causation, generating a kind of alternate world of “scholarship” vigorously debated in incredibly devoted circles of human activity. I sometimes wonder what would happen if similar numbers of the reading public shared the same fanboy obsessiveness for the labor movement, the civil rights movement, or the Greek polis. Maybe Nietzsche was right about the mood of self-irony or “congenital grayness” in modern culture even 140 odd years ago. In a world so thoroughly disenchanted, and with politics so nihilistic, why not turn to stories of gods and their interaction with mortal beings? How different is that from the Homeric tales that so inspired cultural unity in the Athenian polis, for example? I shudder to think Stan Lee is our Homer, but there you have it. If nothing else, the sinking feeling that goes along with my awful observation should goad us historians to write more inspiring stories—or it speaks to Nietzsche’s larger diagnosis of our modern condition, which becomes at bottom ironic. It comes as no surprise, as Jennifer Ratner Rosenhagen has explored elsewhere, that the Ubermensch, now in the form of long dead Friedrich Nietzsche himself, has reappeared occasionally in the garb of Superman.

[1] Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, “On the Utilities and Liabilities of History for Life,” in Unfashionable Observations, Richard T. Gray, trans. The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, vol. 2, (Stanford University Press, 1995), 154.

[2] I’ve borrowed this line from Martin Griffin’s really lively USIH entry on Melville from a few months ago.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

“I want to say, “folks, I’m trying to teach your precious child how to avoid becoming an asshole.”

This is the best answer to that question ever.

I’ve really enjoyed reading this series, Pete. Thanks for writing it.

Thanks so much Robin. I’ve got to meet with parents at a preview day this weekend and it’s gonna be really hard to restrain myself. That one rolls around in the back of my head almost every time.