Editor's Note

This post is written by Holly Genovese, S-USIH blogger and a specialist in the Black Power movement, intellectual history, and the history of the carceral state.

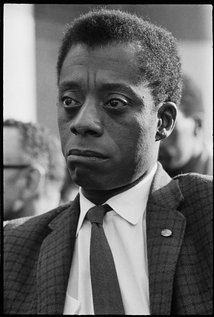

James Baldwin has enjoyed somewhat of a cultural renaissance in the last few years, with the release of I Am Not Your Negro and the allusions modern writers like Jesmyn Ward and Ta-Nehisi Coates have made to him in their work. Baldwin seems a writer for the era of Black Lives Matter and Donald Trump, though much of his work was written a half century ago. Though modern writers, activists, and intellectuals have recently reflected on his work, Baldwin’s work was not without controversy during his lifetime, though few critiqued him more harshly than Harold Cruse.

In honor of the anniversary of Harold Cruse’s magnum opus The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, I will focus on his interpretation and criticism of James

Baldwin. The book is lengthy and hits on a very diverse array of figures in African American intellectual history, but Cruse had harsh words for Baldwin, though Crisis was full of criticism of many other revered figures. Even more evident than this argument, though, is Cruse’s call for pragmatic answers to the issues facing African Americans. For Cruse, there was little point for the rhetoric of Baldwin if he didn’t have a coherent worldview, a knowledge of history, and planned solutions.

It’s even more interesting that Cruse critiques Baldwin on these elements, because Baldwin famously tried to distance himself from the “protest novel,” literature that was prescriptive and born with an activist purpose in mind. For Baldwin, what Cruse demands makes bad literature. For Cruse, there is little role for writers and intellectualism that offers little practical solutions.

But I will argue, in this piece, that the lack of explicit pragmatic suggestions in Baldwin’s work is what has ensured his legacy and the strong connection 21st century African American writers have with him. In his book Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates framed his book as a letter to his son, a clear reference to Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. Toni Morrison even referred to him as the next James Baldwin in her blurb of the book. In a 2015 Atlantic Monthly essay, Michal Eric Dyson reflected on the intellectual connection between Baldwin and Coates when he wrote

I also admire those who take the time to figure the reasons for the rebellion in the streets. Coates need not ever speak at a rally to be heard there, especially by those who are fed by his ravenous intellect and who drink in his considerable insight. His writings compose a powerful moral force for good; his words aid a thinking populace to find its ethical orientation and its justifications for action.

To Cruse, Baldwin’s writing is little more than a “futile rhetorical exercise” because of his lack of interest in specific policy solutions. But as Dyson wrote about Coates, a writer does not have to himself be in the streets to impact that work that happens there. For many involved in the Black Lives Matter movement and other activism in the last few years, Coates’ work has served as essential inspiration. The relationship between Coates’ writing and Baldwin’s shows the continued relevance and influence of Baldwin’s work. Not because Baldwin had it “right” or offered the solution to racism and white supremacy in the United States, but because his words still reverberate half a century removed.

According to Cruse, while Baldwin’s writing was popular, it was also “superficial” in contrast to social reformers and radical political activists. It did not  matter how many social reformers and activists sought solace in his work. It did not matter that Baldwin left America for France because he could not cope with reality of life as an African American man in the United States. What mattered, to Cruse, was the lack of objectivity and lack of specifics found in Baldwin’s work.

matter how many social reformers and activists sought solace in his work. It did not matter that Baldwin left America for France because he could not cope with reality of life as an African American man in the United States. What mattered, to Cruse, was the lack of objectivity and lack of specifics found in Baldwin’s work.

Interspersed among Cruse’s critiques of James Baldwin is an obvious anti-semitism. Though Cruse’s anti-semitism may seem unrelated to Baldwin, Baldwin’s lack of animosity towards Jewish people in Harlem infuriated Cruse. To Cruse, much of the exploitation of African American works was at the hands of the Jewish, who to Cruse, also benefited from the oppression of African Americans. Cruse couldn’t see Baldwin’s differing opinion as anything other than a lack of connection to reality and a lack of historical knowledge.

Cruse emphasizes the importance of “facts” and poses them as opposites to emotion, and to the kinds of writing that Baldwin did. While Baldwin’s non-fiction was often based on a particular cultural encounter or piece of art, Baldwin lacked the kind of systematic evidence that Cruse preferred. This enlightenment ideal reflects Cruse’s own ideology, which focused heavily on African Americans owning their own economic resources.

It seems to me, that Cruse was wrong about many things, but most important among them the significance of Baldwin. As a new generation of scholars, activists, and readers discover his work, it only becomes more clear how true is lacks of “fact” and “evidence” are. But Cruse does bring much to discussions about the role of the intellectual and the role of intellectual history. Should a writer, or an intellectual, offer practical proposals? Does their argument need to be steeped in fact? And is an influence on activists and politicians enough to make writing significant? I can’t answer these questions here, but Cruse’s depiction of Baldwin, though flawed, has me rethinking the role and purpose of “the intellectual” all these years later.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Insight is intriguing but do you not think that if Cruse sought pragmatic solutions in his times, the re-birth and fame of Baldwin and similar works may be due to the fact that there remains a great absence of thought and actions toward pragmatic solutions to the problems facing African Americans. Are they still exploited [willingly and unwillingly] by the Jewish ethnic group and/or others? Is the presence of Baldwin’s rhetoric an illustration of Cruse’s dilemma with fiery rhetoric with no bite or plan to help change the situation; and to move Cruse forward would Cruse have a problem with Coates and black intellectuals of the contemporary times? Where are the plans?

Hi John! Thank you so much for your thoughtful comment! I think it’s definitely possible-and Baldwin’s continued relevancy is no doubt because racism/white supremacy/etc. I just wonder why Cruse would, instead of taking Baldwin for what he aims to do, creates a standard of policy proposal/specific action that may just not be the role of the intellectual, or at least every intellectual. It think Cruse would certainly levy the same critiques at Coates-but I think Coates’ relationship to BLM (and the syllabi and anthologies that have proliferated) show the relationship between these works and action.

Thanks Holly for this summary; I’ve always wondered what Cruse’s problem with Baldwin could possibly be.

Among many other problems with his critique — and, not disconnected, critiques of Coates for being too fatalistic/mum-on-policy — is the issue of first simply establishing that a problem exists. I read Baldwin, and Coates, as talking to a white audience who by and large either do not believe white racism exists, or do not understand how extensive and integral it is to America. Most of their energy is focused on driving this point home, especially to liberals who are quick to nod “oh yes, of course” but then back away from the implications and commitments truly involved in such a recognition. Considering what an uphill battle that remains — that Baldwin and Coates remind so many people of us each other is, in fact, rather depressing when you think about it — it seems ungenerous in the extreme for someone to essentially respond, “well alright smarty pants, now that you’ve got that off your chest, what do you actually propose to *do* about it?” But how in the world was Baldwin, or Coates today, going to offer a roadmap out of racial inequality and violence when we’re still stuck in the Bizarro Mode of denying that it even exists?!

Moreover, the “this is just not productive” critique is a legitimate one in some cases, but also makes for easy objections by those not really sympathetic to the analysis in question in the first place. Who ever says, “the author gets this slam-dunk, totally right, but what can I say, they offer no solutions. FAIL.” Very rarely.