Editor's Note

This post comes to us from Matthew D. Linton, who is the Rose and Irving Crown Fellow at Brandeis University. His dissertation, “Understanding the Mighty Empire: China Studies and the Construction of Liberal Consensus, 1928-1980,” examines the development of academic China scholarship and the field’s relationship to domestic liberal politics. This post is the third part of a series Matt is writing on the intellectual history of country music; his previous entries can be found here and here.

In his 2015 book Noise Uprising: The Audiopolitics of a World Musical Revolution, Michael Denning explores the musical revolution that took place in port cities ranging from Havana to Jakarta between 1925 and 1931. Facilitated by the inexpensive mass production of shellac records, new genres of music like jazz, samba, and kroncong sprouted up as old musical forms were translated, fused, and transported across a world united by water. This was not merely an artistic revolution, however. They were also “fundamental to the extraordinary social, political, and cultural revolution that was decolonization.”[1] This audiopolitics of revolution, as Denning calls it, gave voice to subaltern peoples languishing under Western colonialism as it transformed colonized and colonizing ears to favor vernacular music. It was an important first step to territorial decolonization. “[T]his noise uprising was prophetic,” Denning argues, “it not only preceded but prepared the way for the decolonization of legislatures and literatures.”[2]

In his 2015 book Noise Uprising: The Audiopolitics of a World Musical Revolution, Michael Denning explores the musical revolution that took place in port cities ranging from Havana to Jakarta between 1925 and 1931. Facilitated by the inexpensive mass production of shellac records, new genres of music like jazz, samba, and kroncong sprouted up as old musical forms were translated, fused, and transported across a world united by water. This was not merely an artistic revolution, however. They were also “fundamental to the extraordinary social, political, and cultural revolution that was decolonization.”[1] This audiopolitics of revolution, as Denning calls it, gave voice to subaltern peoples languishing under Western colonialism as it transformed colonized and colonizing ears to favor vernacular music. It was an important first step to territorial decolonization. “[T]his noise uprising was prophetic,” Denning argues, “it not only preceded but prepared the way for the decolonization of legislatures and literatures.”[2]

American country music presents a problem for Denning. On the one hand, it was – with jazz – a major part of American vernacular music. Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family recorded hit records in Bristol, Tennessee, bringing the “hillbilly” music of Appalachia a national audience. On the other hand, neither country musicians nor Bristol fit seamlessly into Denning’s narrative. While economically poor, the founding generation of country musicians was not colonized like Denning’s Indonesian kroncong musicians or Hawaiian hula singers. Bristol is also not a port city and therefore not part of the international circulations of goods and peoples that took place in Havana or New Orleans.

In this essay, I find in early country music of the 1940s through the 1960s a similar melding of music and politics, but for a different end. Instead of celebrating musical fusion as a way to upset established hierarchies, the country music of Rodgers’ heirs Ernest Tubb and Hank Snow sang songs that celebrated American empire. Like the poetry of Rudyard Kipling, Tubb and Snow’s music highlighted the burden and sacrifice of American men liberating foreign peoples. They then brought that message to rural audiences through new recording technology. This audiopolitics of empire was crucial in marketing American empire to the homefront as well as defining it as fundamentally white and male.

Ernest Tubb seemed an unlikely heir to Jimmie Rodgers’ pioneering legacy. Born in northeast Texas in 1914, Tubb became a fan of Rodgers in his teens playing with local bands in and around San Antonio.[3] After Rodgers’ death in 1933 from tuberculosis, Tubb contacted his widow, Carrie Rodgers, to get an autographed photograph beginning a lasting friendship that saw her help his career by giving him Jimmie’s guitar and connecting Tubb to local DJs. A tonsillectomy in 1939 changed Tubb’s voice to a deep baritone, however, making it difficult to sing “high and lonesome” yodels in Rodgers’ style. Still, despite his vocal limitations, Tubb had his first major hit one year later with “Walking the Floor Over You” (1940), which established him as an up-and-coming country star. As a result of the single’s success, Tubb was invited to join the Grand Ole Opry in 1943 and would remain in Nashville for the rest of his life.

Tubb was not drafted into World War II, but he recalibrated his music for wartime. His single, “Soldier’s Last Letter” (1944), for example, told the story of a mother receiving and reading a letter from her son who was fighting abroad. Tubb’s song was both timeless and timely. It drew on a long history of war ballads including American Civil War ballads-turned-standards like “Farewell, Mother” and “When Johnny Comes Marching Home.” Unlike the folk music of Woody Guthrie or Leadbelly’s blues, which denounced the particularities of fascism, its themes of a grief-stricken mother reading her son’s final words before dying in battle spoke to universal themes of loss and sorrow that stalked home fronts during wartime for centuries. At the same time, “Soldier’s Last Letter” captured the spirit of the age and resonated in a country mobilized for total war.

“Soldier’s Last Letter” was also a shrewd business strategy for Tubb. It reached number one on the country music charts. It aligned Tubb with American nationalism and made him a champion of the American armed forces – the beginnings of what would be a unifying theme of country music up to contemporary artists like Toby Keith. Tubb followed the success of “Soldier’s Last Letter” with two more singles, “Keep My Mem’ry in Your Heart” (1945) and “It’s Been So Long Darling” (1945), that spoke about men forced to go away and the difficulties leaving the ones they love. The latter also reached number one, cementing Tubb as one of the most recognizable and popular voices in country music.

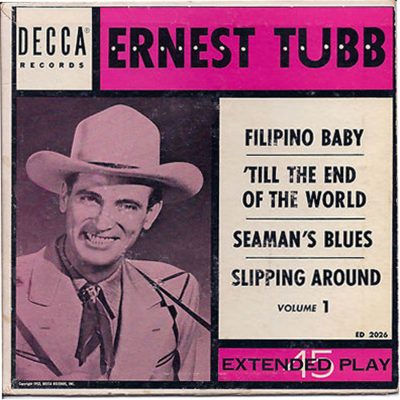

America’s triumphant end to World War II left the nation with a “preponderance of [global] power,” to use diplomatic historian Melvyn Leffler’s phrase.[4] Tubb translated his wartime feelings of loss to an international community yearning for American leadership at war’s end. In 1946, he released “Filipino Baby,” which flipped the perspective of loss from the homefront to the international arena. The song takes place on a military ship departing Manila Bay. Soldiers are swapping stories and photographs of local women they had taken as “lovers” during their time stationed in the Philippines. One man vows to return to Manila to marry his “Filipino baby” and, in what can be interpreted either as a fantasy or flash-forward, Tubb sings of a marriage ceremony on the boat between the American “returned from Caroline” and his Filipino baby.

Tubb’s song came at an anxious time for American empire. On the one hand, Americans were spread the world over shoring up and rebuilding countries from Japan to Germany. Never had the United States played such a large role in the domestic politics of sovereign nations. At the same time, however, imperial ambitions were running against anticolonial nationalism that demanded self-rule for colonized peoples in Africa, Asia, and Oceania. The Philippines was one such nation, granted independence from the United States in 1946. It thus becomes possible to hear “Filipino Baby” as a story of imperial return. Like the sailor departing Manila Bay at war’s end, the United States granted the Philippines its independence. Yet, this parting was not absolute but instead was the beginning of a new phase of US-Philippines relations where direct colonial control was replaced with a contracted network of military bases and economic aid.

Tubb’s song came at an anxious time for American empire. On the one hand, Americans were spread the world over shoring up and rebuilding countries from Japan to Germany. Never had the United States played such a large role in the domestic politics of sovereign nations. At the same time, however, imperial ambitions were running against anticolonial nationalism that demanded self-rule for colonized peoples in Africa, Asia, and Oceania. The Philippines was one such nation, granted independence from the United States in 1946. It thus becomes possible to hear “Filipino Baby” as a story of imperial return. Like the sailor departing Manila Bay at war’s end, the United States granted the Philippines its independence. Yet, this parting was not absolute but instead was the beginning of a new phase of US-Philippines relations where direct colonial control was replaced with a contracted network of military bases and economic aid.

If Tubb’s “Filipino Baby” showcased country music’s place connecting World War II military success to its postwar empire-building in Asia, one of his first recruits to the Grand Ole Opry, Hank Snow, showed country music’s transnational reach. Born in Nova Scotia, Canada and raised in an abusive household, Hank Snow sought escape in the music he heard on his mother’s radio.[5] The Canadian maritimes, like port cities around the world, was connected to music from across the world in the 1920s and young Hank Snow became entranced by the sounds of Hawaiian steel guitar music. Scraping together their meager earnings, Snow’s mother bought a steel guitar from a catalog. From the outset, Hank showed musical talent and he eventually moved to Montreal in the 1930s to pursue a music career. In Montreal, Snow fell in love with the music of Jimmie Rodgers and reinvented himself as a singing cowboy. Finding modest success in Canada, Snow traveled to Wheeling, West Virginia in 1944 before permanently settling in the United States. On a 1948 tour of Texas, he met Ernest Tubb who invited him to perform at his Cowtown Jamboree in Dallas.[6]

In Snow, Tubb found a performer with considerable talent and similar interests. Snow was a guitar whiz and his high-pitched, nasal voice made him a natural fit for Texas country ballads. The two men were also united by their economic woes during the Great Depression and by their love of Jimmie Rodgers. Furthermore, both men had found success during World War II as patriotic symbols: Tubb as a country crooner and Snow as a radio DJ. It is no accident that one of Snow’s first American recordings was a cover of Tubb’s “Soldier’s Last Letter.” Snow’s first number one hit, “I’m Movin’ On” (1950), followed soon after and he became a regular on Tubb’s Grand Ole Opry.

In Snow, Tubb found a performer with considerable talent and similar interests. Snow was a guitar whiz and his high-pitched, nasal voice made him a natural fit for Texas country ballads. The two men were also united by their economic woes during the Great Depression and by their love of Jimmie Rodgers. Furthermore, both men had found success during World War II as patriotic symbols: Tubb as a country crooner and Snow as a radio DJ. It is no accident that one of Snow’s first American recordings was a cover of Tubb’s “Soldier’s Last Letter.” Snow’s first number one hit, “I’m Movin’ On” (1950), followed soon after and he became a regular on Tubb’s Grand Ole Opry.

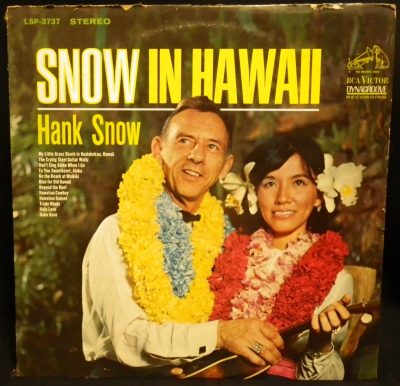

During the 1950s, Tubb and Snow married the transnational roots of American country music to a nationalist message. These songs often resulted in a fascinating combination of pre-electric sounds from across the globe. Snow’s “The Rhumba Boogie” (1951), for example, used South American and Cuban motifs and layered them over a Hawaiian steel guitar. They were also almost always from an American (or in Snow’s case North American) perspective. Songs like “Caribbean” and “Calypso Sweetheart” were the musical accompaniment to the tiki bars, Polynesian cuisine, and Hawaiian vacations that characterized middle class leisure in the late 1950s through the mid-1970s.

Snow also sometimes imitated local vernaculars. On “Calypso Sweetheart,” for example, his lyrics are in broken English to both make the song’s Trinidadian locale more exotic for his American audience and sound like he imagined people in other, “less-developed” countries spoke his native tongue. Most importantly, the foreign subjects of these songs always welcomed their North American guests recognizing their superiority as consumers, lovers, and allies.

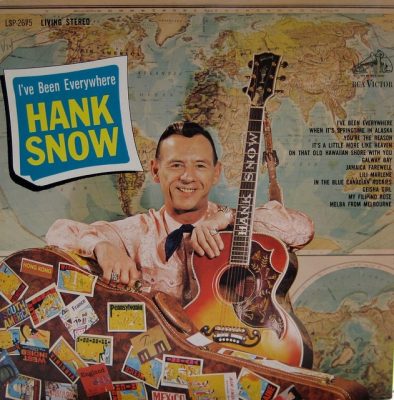

The apex of country music’s midcentury fascination with foreign subjects was Snow’s landmark “I’ve Been Everywhere” (1963). The album was a tour across America’s cultural empire. The famous opening single of the same title was originally an Australian song with Australian place names. Snow’s writers substituted in American and Canadian locales. The song was a number one hit for Snow and has been covered by singers ranging from Johnny Cash to Kacey Musgraves. If the lead single garnered most of the attention, the other songs on the album seamlessly tie American territories turned vacation-states (Alaska and Hawaii) to other nations connected to the United States via cultural influence or military occupation. All the songs about foreign nations fit into the American conqueror, non-white submissive, male-female sexual relationship model made famous by Tubb. “Jamaica Farewell” and “Geisha Girl” are lovelorn ballads in the mold of Tubb’s “Filipino Baby.” Country music like Snow’s “I’ve Been Everywhere,” was the soundtrack for what historian Naoko Shibusawa has called “the mutually reinforcing frameworks of gender and maturity” which subsumed “racial hostility” beneath familiar domestic hierarchies.[7] Snow’s American empire was both an erotic escape for American men living mundane, comfortable middle class lives and a place that enthusiastically welcomed the United States as a bearer of wealth and civilization.[8]

The apex of country music’s midcentury fascination with foreign subjects was Snow’s landmark “I’ve Been Everywhere” (1963). The album was a tour across America’s cultural empire. The famous opening single of the same title was originally an Australian song with Australian place names. Snow’s writers substituted in American and Canadian locales. The song was a number one hit for Snow and has been covered by singers ranging from Johnny Cash to Kacey Musgraves. If the lead single garnered most of the attention, the other songs on the album seamlessly tie American territories turned vacation-states (Alaska and Hawaii) to other nations connected to the United States via cultural influence or military occupation. All the songs about foreign nations fit into the American conqueror, non-white submissive, male-female sexual relationship model made famous by Tubb. “Jamaica Farewell” and “Geisha Girl” are lovelorn ballads in the mold of Tubb’s “Filipino Baby.” Country music like Snow’s “I’ve Been Everywhere,” was the soundtrack for what historian Naoko Shibusawa has called “the mutually reinforcing frameworks of gender and maturity” which subsumed “racial hostility” beneath familiar domestic hierarchies.[7] Snow’s American empire was both an erotic escape for American men living mundane, comfortable middle class lives and a place that enthusiastically welcomed the United States as a bearer of wealth and civilization.[8]

An odd coda to Snow’s career as a promoter of American empire came in 1968. With sales sagging, he decided to help famed segregationist George Wallace campaign for President. For a musician whose career had largely been built upon songs celebrating interracial unions, Snow’s support for Wallace appears as a dramatic break with his prior persona. A more thorough examination of Snow’s discography, however, reveals lyrical themes consistent with white supremacy (though Snow was not known to harbor any personal prejudice against non-whites).[9] Country music’s audiopolitics of empire was a white supremacist vision of international relations. If Snow’s protagonists often had relationships with non-white women, those women were never equal partners. Non-white men were wholly absent. Snow’s songs were a sonic update of traditional colonial fantasies of white men “going native” – sleeping with native women and enjoying foreign cultures as an escape from the “white man’s burden” at home and abroad.

Country music’s audiopolitics of empire was borne in the glow of America’s World War II victory and continued throughout the mid-20th century. It portrayed peoples in Asia and the Caribbean as enthusiastic supplicants to the American imperial project, welcoming American men with a rum swizzle and the promise of sexual release. The audiopolitics of empire made foreign domination more than a dreary responsibility, it made empire fun. Ultimately, this vision of American empire could not survive the Vietnam War. Country artists like Merle Haggard recast empire as a heavy burden that required self-mastery and restraint, not fun and adventure. Though the need for empire remained, its theme music had changed.

Notes

[1] Michael Denning, Noise Uprising: The Audiopolitics of a World Musical Revolution (New York City: Verso, 2015): 6.

[2] Denning, Noise Uprising, 9.

[3] Ronnie Pugh’s Texas Troubadour is a fantastic biography of Tubb and essential reading for an understanding of his early years as a Rodgers acolyte and impersonator. See, Ronnie Pugh, Ernest Tubb: The Texas Troubadour (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998).

[4] Melvyn Leffler, A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992).

[5] For a useful biography see, Vernon Oickle, I’m Movin’ On: The Life and Legacy of Hank Snow (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, LTD., 2014).

[6] Oickle, I’m Movin’ On, 91.

[7] Naoko Shibusawa, America’s Geisha Ally: Reimagining the Japanese Enemy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006): 5-6.

[8] Though women were less likely to write on international subjects, a few, like Wanda Jackson, did have considerable success as chroniclers of American empire. On her “Fujiyama Mama” (1957), Jackson uses the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a metaphor for the fury she is about to inflict on her erstwhile beau. This is an interesting appropriation of American military technology (she also mentions nitroglycerine) as a tool for female empowerment. It should be noted, however, that Jackson was not a typical country artist. She drifted between rockabilly and country and her more lyrically adventurous songs fall solidly in the rockabilly camp.

[9] Snow and his biographers have ignored his campaigning for Wallace. Most of the limited work on Snow is uncritical, lauding his rise from poverty to country music stardom.

8 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This is a fascinating post, Matthew–thanks for writing it! I can’t help but think of *Black Star, Crescent Moon* by Sohail Daulatzai on black American hip hop and the Muslim World in the 1980s and 1990s. It’s an interesting contrast with what you argue here, where in hip hop many of the artists profiled there talk about solidarity with peoples in the Middle East and West Asia. It’s not a surprise such a contrast is there, but reading your piece suddenly reminded me of that book.

Thanks, Robert. I’ll have to check Sohail’s book out. Sounds fascinating.

I think this is a very compelling and enjoyable essay, but I’d push back a little at the way in which the term “empire” is made to do so many duties at once. In particular, I think it’s more useful to distinguish more sharply between the war against fascism and the project to establish a US military and political presence across the globe (one might call it the FDR era vs the John Foster Dulles era), otherwise the price paid by Americans to defeat the Axis powers gets conceptually contaminated by the later events. I concede that this is an ethical (or, if you prefer, ideological) point rather than a historical one — and I’m not a historian — but even from an historical standpoint, it doesn’t seem to me to clarify anything to take the distinctive experience of the U.S. in WW2 and slide it under a notion of empire than sits over the period like a heavy conceptual blanket.

Also, I think it’s worth suggesting that empire and nationalism are not, or not always, just two surfaces of one ideological coin. Empires often develop a relatively open social order, possibly linked to the need for increased transport and communication, and one may see the appearance of a type of anti-imperialist nationalism that seeks to represent a favored demographic and/or cultural isolationism that the nature of empire tends over the longer arc to undermine. To that extent, country music may express a conservative distaste for empire that is basically a resistance to empire’s transcultural dynamics.

Martin,

I don’t want to speak for Matt, but the way I understand the imperial context for WWII has a lot to do with why US forces were in places like the Philippines or Hawaii to begin with. The prior imperial ventures which established the United States as a Pacific power set the table, so to speak, for war with Japan. That does not mean we have to label WWII an imperialist war, but it does mean that U.S. imperialism is an important lens for understanding the origins, course, and outcome of the war.

Andy — I would agree completely that the lens of imperialist expansion cannot be ignored when considering the war in the Pacific (and not just American, but also British, French, and Dutch — and of course the ambiguous Japanese imperial project itself). There is a good argument to be made that the Pacific theater was, in key respects, much more of a “traditional” colonial/anticolonial war than the conflict in Europe. The only consideration I’d throw in would be that perspectives were not frozen and tended to shift with events: for example, the Viet Minh did not see the U.S. presence in the Pacific region as a danger to Vietnamese independence in 1945, but by 1950 they did. Partly due to the larger Cold War, partly due to the French winning over the Truman administration to their side, partly due to race — a combination of factors.

Martin,

Sorry for the slow reply. I see what you mean. I do not mean to conflate Tubb’s early World War II pro-military songs with his postwar imperial work. I do see Tubb’s wartime work influencing his later work in one important way. Achieving success as a songwriter of the American military during the war leads Tubb down a path to imperial as World War II ended and a new American empire emerges. To echo Andrew’s comment, the military is the institution that links Tubb’s war songs with his empire songs. Themes of leaving and loss unify the two songs even though the context, as you rightly point out, has changed.

I think your notion that in the United States there is a conservative distaste for empire may be true, but I do not see it reflected in country music. Where there are critics of America’s international involvement in country music, it comes from the left where folks like John Prine questioned the human costs of American involvement in Vietnam. There is an insularity to certain sides of country music (like Red Dirt, which focuses almost solely on life in Texas and Oklahoma) and a rural agoraphobia, but I don’t see isolationism as a major strand. Country music is very class conscious, but it’s more close to home. Working class anger is aimed at the factory foreman and not at the level of attacking cosmopolitan business executives (at least from the right).

Bristol not a port city? I stopped reading at that point. Bristol was a port city from way back – and a major player in the triangular trade. It was only later in the 20th century when Bristol bound ships stopped at Avonmouth, Bristol’s port. I remember an American Frigate being tied up in the centr of Bristol in about 1944.

The reference in the post is to Bristol, Tennessee (not the English Bristol, which is what you seem to be referring to).