Editor's Note

This essay by Michael J. Kramer is the second contribution to our Summer of Love Roundtable. (The first roundtable installment is here.) Kramer works at the intersection of historical scholarship, the arts, digital technology, and cultural criticism. Michael J. Kramer specializes in modern US cultural and intellectual history, transnational history, public and digital history, and cultural criticism. He is an assistant professor of history at the State University of New York (SUNY) Brockport. His website can be found at michaeljkramer.net.

The Negative Dialectics of the Summer of Love:

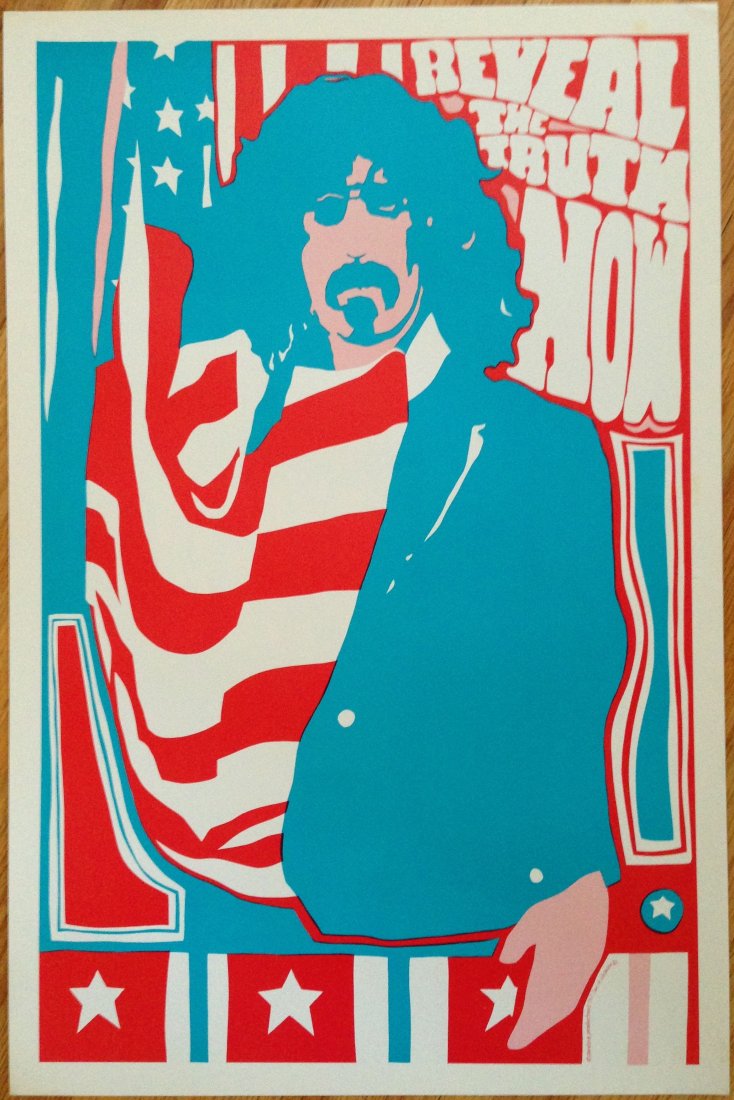

Frank Zappa’s We’re Only In It For the Money

by Michael J. Kramer

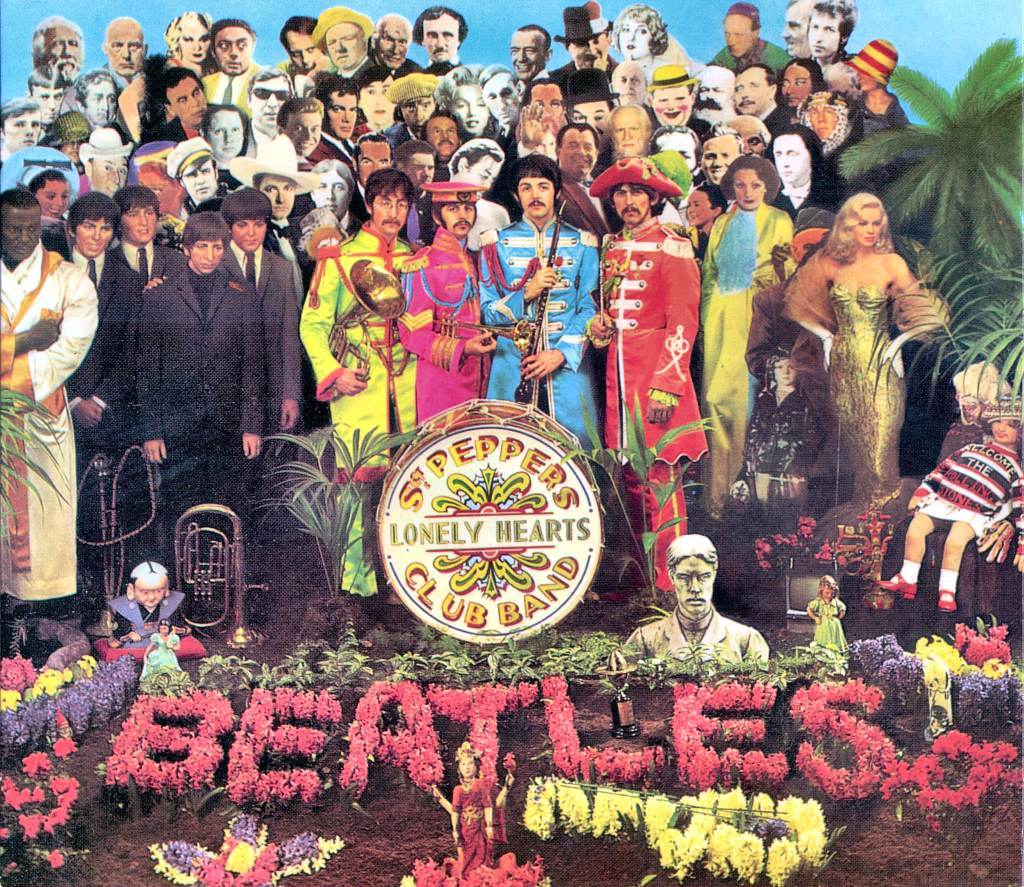

It was fifty years ago today (roughly) Sgt. Pepper taught the band to play. Many, therefore, justifiably might turn to The Beatles’ groundbreaking art-rock album to make sense of the history of the Summer of Love. After all, upon its release in June of 1967, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band was celebrated by literary critics such as Richard Poirier, Benjamin Demott, and Kenneth Tynan, among others, as rock’s first highbrow masterpiece.[1] In the hip enclaves of the Western world such as San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, ground zero for the Summer of Love, its sounds were unavoidable. One supposedly could not walk down the street in the Haight without hearing the Fab Four’s psychedelic tunes wafting out of the windows of the old Victorians that were fast becoming communes and crash pads for young people with flowers in their hair (if the Grateful Dead were not drowning out The Beatles that day with a free concert down in the Golden Gate Park Panhandle).[2]

Yet there was something overripe and curdled about Sgt. Pepper even upon arrival, as infamous reviews by the likes of Richard Goldstein in the New York Times declared at the time[3]

Yet there was something overripe and curdled about Sgt. Pepper even upon arrival, as infamous reviews by the likes of Richard Goldstein in the New York Times declared at the time[3]

, just as there was something rather rotten right away about the supposed utopia of the Haight (the Dead, like many of the early bohemians in the Haight, would soon be gone from the neighborhood precisely for this reason[4]). In his remarkable book on the Beatles, Magic Circles, Devin McKinney calls Sgt. Pepper—and the broader hippie counterculture as a whole—a “cover-up.” Here is a challenging critique of the continued nostalgia for the Summer of Love that lingers, like stale patchouli, even to this day. McKinney argues that Sgt. Pepper “was the Beatles’ concerted if not quite conscious effort to draw a closed circle—around themselves and that portion of the audience which shared its fantasy of the moment.” To McKinney, the album was “quite possibly the most brilliant fake in rock and roll history…but a fake of its time, and for its time.” A kind of treatise on how “all you need is love,” The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper was, to McKinney, “the bright shining lie they offered to the world—and themselves!—that such a utopia of mind, body, and spirit as the album represented was the natural and only possible culmination of all that had preceded it.”[5]

Not everyone was convinced. There were other sounds besides Sgt. Pepper being concocted in 1967, other pop music masterpieces, sensibilities, and cultural stances—even, we might say, intellectual positions. To understand the Summer of Love more compellingly requires taking them, like Sgt. Pepper, seriously (although, as we shall see, perhaps not too seriously since seriousness was part of the problem with the Summer of Love). It means expanding what counts as an intellectual tract, as a complex statement of ideas, as intellectual history. It means thinking of the Summer of Love as a richly multifarious ideational world, swirling with debate, discussion, analysis, response, critique, engagement—in short, with thought. This is difficult to do, since it was a moment in which many turned intensely to the experiential, sensorial, and corporeal, but it is invaluable for making better sense of that odd historical moment.

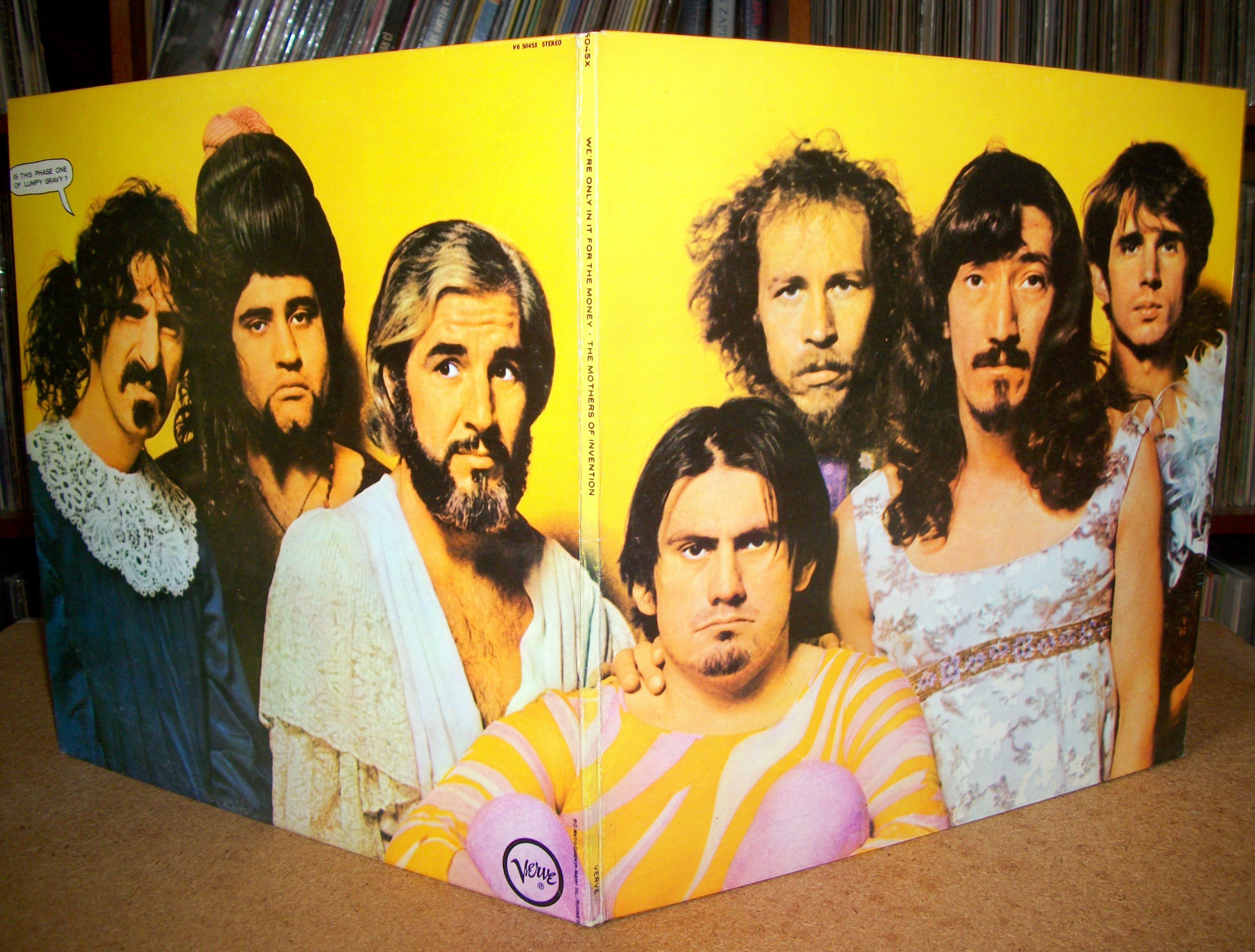

One album that was in direct conversation with Sgt. Pepper was the remarkable LP We’re Only In It For the Money, recorded in the summer and fall of 1967 by Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention band, but for reasons that will quickly become obvious, not released until March 1968.[6] It was a biting satire of the hippie countercultural phenomenon. Yet it was created, crucially, from within the belly of the beaded and bell-bottomed beast. As the title suggests, on We’re Only In It For the Money Zappa offered a self-corrective critique of the hippie fad, a hilarious burlesque that sticks a finger in the kaleidoscope eyes of overindulgent, overweening hippiedom. Lucy is most definitely not in the sky with diamonds on this record.

We’re Only In It For the Money, funny as it is from the title on through its spinning grooves, is not merely a parody. It is not neither merely a kind of aural Mad magazine sendup of hippies and the counterculture, nor a reactionary screed. While not many noticed it at the time, the album’s absurdist satire masks an earnest effort to articulate what a true Summer of Love might achieve, what an authentic and broad-reaching Human Be-In might actually be like in place of the one in January of 1967 that served as the first clarion call to wear flowers in your hair and storm the City by the Bay. On We’re Only In It For the Money, Zappa presented a Summer of Love even Theodor Adorno could fall in love with: here was a critique born out of deep engagement with the emotional, social, and intellectual longings buried within the counterculture’s yearning quest; in making a damning critique of the Summer of Love, Zappa identified false emancipations in dogged pursuit of the real thing.[7]

We’re Only In It For the Money, funny as it is from the title on through its spinning grooves, is not merely a parody. It is not neither merely a kind of aural Mad magazine sendup of hippies and the counterculture, nor a reactionary screed. While not many noticed it at the time, the album’s absurdist satire masks an earnest effort to articulate what a true Summer of Love might achieve, what an authentic and broad-reaching Human Be-In might actually be like in place of the one in January of 1967 that served as the first clarion call to wear flowers in your hair and storm the City by the Bay. On We’re Only In It For the Money, Zappa presented a Summer of Love even Theodor Adorno could fall in love with: here was a critique born out of deep engagement with the emotional, social, and intellectual longings buried within the counterculture’s yearning quest; in making a damning critique of the Summer of Love, Zappa identified false emancipations in dogged pursuit of the real thing.[7]

Born in 1940, Frank Zappa grew up in and around the Cold War defense industry, in which his father worked, deeply alienated and brilliantly smart. He became a strange, inventive, and anti-authoritarian musician, as interested in the difficult sounds of avant-garde composer Edgard Varèse as the latest rhythm and blues hits of the 1950s. Coming of age on the edge of the Mohave Desert to the east and greater Los Angeles to the west, Zappa was deeply alienated by the conformist consumer culture developing around him.[8] He might even be thought of as a kind of teenage version of Frankfurt School intellectuals such as Adorno himself and Max Horkheimer, who arrived in Los Angeles in the 1940s as critical theory emigres from Nazi Germany alongside comrades such as Bertolt Brecht and Arnold Schoenberg.[9]

Zappa was not a hippie. He was a freak. As commentators such as art critic Dave Hickey and Deadhead scholar Steve Silberman, among many others have noted, there was a big difference between the two.[10] As one early Haight-Ashbury resident, Carl Gottlieb, put it, “We called ourselves freaks, never hippies…hippies were people who borrowed your truck and didn’t return it.” Another, Pat “Sunshine” Nichols, disdained hippies as “people who just kind of showed up and didn’t seem to have any sense. They didn’t know how to take care of themselves. They didn’t know how to wash their clothes, hold down a job, or make sure they were going to live through it.” She thought of herself as a beatnik.[11] In Southern California, Zappa helped shape the “freak” response to the surrounding world of “plastic people,” as Zappa called them, with albums such as 1966’s Freak Out! and 1967’s Absolutely Free.[12] By the Summer of Love itself, Zappa and his band had already made a number of trips to San Francisco to perform, including one in 1966 for the third Family Dog concert at Longshoreman’s Hall at an event called “A Tribute to Ming the Merciless,” another to open for comedian Lenny Bruce at the Fillmore Auditorium right at the start of concert promoter Bill Graham’s career, and later co-billings with bands such as the Grateful Dead.[13] During the Summer of Love itself, the Mothers of Invention were ensconced in a residency at the Garrick Theater in New York City, part of the burgeoning Greenwich Village bohemian scene. Zappa had a front row seat (or was on the stage itself) for much of the Summer of Love phenomenon. He didn’t like what he saw.[14]

The liner notes for We’re Only In It For the Money say as much: “This entire monstrosity was conceived and executed by Frank Zappa as a result of some unpleasant premonitions August through October 1967.” But writing is far from the first thing one notices about the album. Instead, it is the daringly overt parody of Sgt. Pepper‘s artwork, which delayed the album’s release by months after it was ready in September of 1967 in order to secure permission from The Beatles’ management. Record company protestations also forced Zappa to reverse the outer and inner sleeves of the LP so that the imitation of Sgt. Pepper appeared within the gatefold instead of on the front of the album.[15] Nonetheless, the imagery got the message across: while Sgt. Pepper

is whimsical, fantastical, dreamlike, even glamorous, with its cast of dozens of celebrities and political figures in Jann Haworth and Peter Blake’s famous photograph, We’re Only In It for the Money is far more outlandish, gross, snotty—in short, it was far more freakish. The Beatles are bedazzling in uniformed regalia, their name beautifully presented in floral arrangements before them. The Mothers are attired in ill-fitting dresses and bathrobes, their name crookedly displayed in an array of carrots and watermelons. As one lyric on the album put it, hair seems to be coming out of every hole in their body. The Beatles were beautiful and hip. The Mothers are ugly and awkward. The Beatles welcome you to the next chapter in their glorious adventure. You might be worried that Zappa and the Mothers are going to do something nasty to you. The Beatles are pop stars. Zappa and the Mothers are mutants. Beautiful people these are not. Freaks is what they are.

The Summer of Love was precisely when the trickle of freaks forming bohemian enclaves in the post-Beat, post-folk revival period of the mid-1960s gave way to a torrent of hippies. Something false was overtaking the challenges to postwar American life that the freaks mounted. A substitution was underway, a bill of goods for the goods themselves. While The Beatles believed you could simply get by with a little help from your friends, Zappa sang, “what’s there to live for / who needs the peace corps?” He did not mean the overseas government program, but rather the legions of young people fleeing to places such as San Francisco. For Zappa, the hype of the Summer of Love was such that now, as he sardonically put it in his lyrics: “Every town must have a place where phony hippies meet / psychedelic dungeons popping up on every street.”

“Who Needs the Peace Corps?” is the first full musical track on We’re Only In It for the Money, but Zappa’s sharp satire explodes from the grooves immediately, even before the song starts with its imitation of the drowsy, loping, modal drones of the San Francisco Sound as put forward by bands such as Jefferson Airplane. The first thing one hears is a British-accented man—possibly guitar god Eric Clapton, who recorded vocal tracks for the album—hitting on a woman. “Outta site, yeah…. Listen, are you hung up?” She laughs uncomfortably. All is not well in the Summer of Love from the get-go, particularly when it comes to the gendered politics of love itself in the romantic sense. Something is off, wrong, inhibiting in its very Playboy-like faux-liberation. Experimental electronic sounds whiz and fuzz around, intensifying the disconcerting vibe. Then a producer whispers something about erasing all the tapes; all is not well either with the means of production. Then after a mock-Jimi Hendrix guitar riff (Hendrix was hanging out with Zappa at the time and even appears on the mock-Sgt. Pepper cover), drummer Jimmy Carl Black, who had been playing with Zappa since 1964, when the Mothers of Invention were but an R&B cover band known as the Soul Giants, makes what would become his trademark line: “Hi Boys and Girls, I’m Jimmy Carl Black, and I’m the Indian of the group.” All is not quite right here with the ethnic politics of the counterculture either, much to the dismay of Human Be-In/Gathering of the Tribes attendees earlier in the year who longed to play Indian themselves (Black himself was of mixed Native American heritage).

Overall, something is immediately and profoundly wrong in Pepperland on We’re Only In It for the Money. Things are not sweetly beatific, but rather wryly ridiculous, perturbed, even sourly rank. In its first verse, “Who Needs the Peace Corps?” nails it right away, with sly references to San Francisco’s concert halls and the Bay Area-based king of LSD Stanley Owsley:

What’s there to live for?

Who needs the peace corps?Think I’ll just drop out

I’ll go to Frisco

Buy a wig and sleep

On Owsley’s floorWalked past the wig store

Danced at the Fillmore

I’m completely stoned

I’m hippy and I’m trippy

I’m a gypsy on my own

I’ll stay a week and get the crabs

And take a bus back home

I’m really just a phony

But forgive me

‘Cause I’m stoned

Zappa and band then musically and lyrically parody Scott McKenzie’s anthemic pop song, “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)”: “Go to San Francisco” they chant. Written by McKenzie and John Phillips of The Mamas and the Papas, “San Francisco” was, essentially, an advertisement for the Monterey Pop Festival, which also took place in June of 1967, just south of San Francisco itself. It was an event that was loathed by San Francisco counterculturalists as a false, overhyped creation by slick Los Angeles musicians and businessmen seeking to cash in on the new subculture of their city to the north.[16] Rumors swirled that The Beatles themselves might show up to perform at the festival. Later, in August, George Harrison would show up in the Haight, and quickly grow dismayed at what he witnessed as various burn outs and demanding fans treated him as if he were a Messiah figure (it probably did not help that he was flying on LSD during the visit).[17] Even one of the members of Sgt. Pepper‘s Lonely Hearts Club Band didn’t need the peace corps, it turned out.

The droning rhythm resumes in the song and Zappa speaks in the character of a new, clueless arrival in San Francisco. He is at once parodying the naïf and, at the same time, slightly sympathetic to his plight:

First I’ll buy some beads

And then perhaps a leather band

To go around my head

Some feathers and bells

And a book of Indian lore

I will ask the Chamber Of Commerce

How to get to Haight Street

And smoke an awful lot of dope

I will wander around barefoot

I will have a psychedelic gleam in my eye at all times

I will love everyone

I will love the police as they kick the shit out of me on the street

I will sleep . . .

I will, I will go to a house

That’s, that’s what I will do

I will go to a house

Where there’s a rock & roll band

‘Cause the groups all live together

And I will join a rock & roll band

I will be their road manager

And I will stay there with them

And I will get the crabs

But I won’t care

“Who Needs the Peace Corps?” is a reminder that not everyone drank the kool-aid during the Summer of Love. Zappa thought the hype about going to San Francisco with flowers in your hair was absurd. It was mindless and a sham, with self-inflicted naiveté substituting for any real wisdom or freedom or even a good time. One had to ask the Chamber of Commerce the way to Haight Street. The pressure of maintaining a “psychedelic gleam” in your eye “at all times” was constant. You were supposed to love everyone, even the police as they beat you up.

Those San Franciscans already in the know saw the flaws of what the Summer of Love became just as much as Zappa did. “The media portrayal of the innocent hippie flower children was a joke,” no less a figure than the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia recalled. “Hey, everybody knew what was happening. It wasn’t that innocent.”[18] As the Dead themselves would put it a few years later in the song “Uncle John’s Band,” burned by the very same problems that Zappa identified right away, “When life looks like easy street, there is danger at your door.”[19] The idea that one could adorn his hair with feathers and flowers, put on some beads, read a book of Indian lore, and leave your shoes back in Des Moines was a farce.

The call to abandon the cities of America for idyllic communes of DIY independence, where hippies and counterculturalists could reconstruct society on their own terms, looked dubious to Zappa as well. On We’re Only In It For the Money‘s next song, “Concentration Moon,” those communes suddenly looked like prison camps for hippies or worse. Zappa and band sang:

Concentration Moon

Over the camp in the valley

Concentration Moon

Wish I was back in the alley

With all of my friends

Still running free

Or maybe these concentration camps had been created in the backlash of a reactionary society threatened even by phony freakdom, never mind the real version:

American way

Threatened by US

Drag a few creeps

Away in a bus

Either way, nothing good was going to come of all this Summer of Love beckoning to come to San Francisco with flowers in your hair. No tangerine trees or marmalade skies waiting there.

Like Sgt. Pepper, the songs on We’re Only In It For the Money move seamlessly one to the next. Other songs continue the critique of phony hippies. “Absolutely Free” calls out the messianic cult of personality that lurked in figures such as Ken Kesey and Timothy Leary in the mid-1960s and led, eventually, to the murderous cult-like madness of Charles Manson. “The first word in this song is discorporate,” Zappa explains, sounding slightly crazy, over a piano introduction. “It means to leave your body.” Then he sings creepily over what sounds like a harpsichord: “Discorporate and come with me / Shifting, drifting, cloudless, starless…. / Unwind your mind….” Then, in what might be one of the origin points for the punk rock that would emerge in the 1970s as a critique of the bloated corporatized hippie-rock of the late 1960s, the next track is titled “Flower Punk.” It features a crazily complex time signature as Zappa and the Mothers satirize the popular garage-rock song of the time “Hey Joe,” best known for the version by Jimi Hendrix:

Hey Joe, where you goin’ with that flower in your hand?

…I’m going up to Frisco to join a psychedelic bandHey Punk, where you goin’ with that button on your shirt?

…I’m goin’ to the love-in to sit & play my bongos in the dirtHey Punk, where you goin’ with that hair on your head?

…I’m goin’ to the dance to get some action, then I’m goin’ home to bedHey Punk, where you goin’ with those beads around your neck?

…I’m goin’ to the shrink so he can help me be a nervous wreck.

Clear-eyed and sober in the midst of the Summer of Love as it was happening, Zappa puts his critique as plainly as he can in “Absolutely Free”: “Flower power sucks!”

At this point, We’re Only In It For the Money might seem like a cynical, despairing dismissal, nothing more than a precursor to Tom Frank’s 1997 history The Conquest of Cool, which lambasted the counterculture as nothing more than “the rise of hip consumerism” as a manufactured act begun on Madison Avenue and come to fruition in the streets of San Francisco and elsewhere.[20] But the end of the album grows more complex, more subtle. In songs such as “Bow Tie Daddy,” “Harry You’re a Beast,” “The Idiot Bastard Son,” and “What’s the Ugliest Part of Your Body?” (answer: “I think it’s your mind”), mainstream America is as much, if not more to blame as hippies for the social crises of the late 1960s. As Zappa intones on “What’s the Ugliest Part of Your Body?”:

All your children are poor unfortunate victims of systems beyond their control

A plague upon your ignorance & the gray despair of your ugly life!…All your children are poor unfortunate victims of lies you believe

A plague upon your ignorance that keeps the young from the truth they deserve!

The problem here, for Zappa, is not that regular America is good and hippies are bad. This is not the “take a shower and cut your hair” reactionary conservatism of Ronald Reagan, himself cashing in politically during this same period with facile critiques of the supposed depravities and decadence of elite youth at the Cal-Berkeley to get elected governor of California. The liner notes of We’re Only In It For the Money went so far as to call the imaginary hippie prison camps in which misfits had been rounded up and sent Camp Reagan. Regular America was, in many ways, even worse than the faux alternative. All the more reason not to let the hippie counterculture off the hook. Witnessing the Summer of Love up close, Zappa characterized the phenomenon as simply the latest commercial lie, a falsely advertised solution to a trumped-up consumer need pushed to the point of desperation. Feel lost, alienated, blue? Feel like a freak? Just buy this hip product and follow our plan and you’ll be healed. You’ll finally feel like yourself, like you belong. Hucksterism was no different dressed in paisley so far as Zappa was concerned.

The problem here, for Zappa, is not that regular America is good and hippies are bad. This is not the “take a shower and cut your hair” reactionary conservatism of Ronald Reagan, himself cashing in politically during this same period with facile critiques of the supposed depravities and decadence of elite youth at the Cal-Berkeley to get elected governor of California. The liner notes of We’re Only In It For the Money went so far as to call the imaginary hippie prison camps in which misfits had been rounded up and sent Camp Reagan. Regular America was, in many ways, even worse than the faux alternative. All the more reason not to let the hippie counterculture off the hook. Witnessing the Summer of Love up close, Zappa characterized the phenomenon as simply the latest commercial lie, a falsely advertised solution to a trumped-up consumer need pushed to the point of desperation. Feel lost, alienated, blue? Feel like a freak? Just buy this hip product and follow our plan and you’ll be healed. You’ll finally feel like yourself, like you belong. Hucksterism was no different dressed in paisley so far as Zappa was concerned.

The fawning innocence of the corporately sponsored Summer of Love was not merely superficial in Zappa’s view, it was darkly destructive. He wanted no part of The Beatles’ closed circle. He wanted to unmask the bright shining lie of The Summer of Love and propose something else: a more difficult path toward, but a better one. In the closing songs of We’re Only In It For the Money, Zappa mapped out an alternative to both the crew-cut mainstream and its phony twin, the long-haired hippie. As if pulling the Summer of Love dream from the clutches of both, he playfully but earnestly sang on the mock-Motown stomper “Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance”:

There will come a time when everybody who is lonely

Will be free to sing and dance and love

There will come a time when every evil that we know

Will be an evil that we can rise above

Here was a very different vision of the strange mix of individual liberation and collective communion at the heart of the Summer of Love’s aspirations. Zappa and the Mothers ecstatically sang together:

Who cares if hair is long or short

Or sprayed or partly grayed

We know that hair ain’t where it’s at!

There will come a time

When you won’t even be ashamed if you are fat!

You did not need to be fab to join Sgt. Pepper’s band. You could be fat. You could look or feel out of sorts, odd, peculiar, queer, off, different. No one had to love to take you home with us, as Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band claimed they wished to do. You didn’t need to be a lovely audience. You did not need to be an artistic genius, a beautiful model, a perfect being. You did not need to have the perfect clothes or join in with the latest fads. Instead, “Who cares if you’re so poor you can’t afford to buy a pair of Mod-A-Go-Go stretch-elastic pants,” Zappa declared. The band joined in, “There will come a time when you can even take your clothes off when you dance!”

The freaks have always come out at night, but in Zappa’s future utopia, they would one day also step into the daylight. The humanistic message was that we are all freaks in one way or another. The pursuit of freedom, the supposed purpose of the Summer of Love, was not to become a hippie in the Haight. It was the dream of being free to be you and me. As rock critic Dave Marsh wrote in 1993, “Zappa stands for life, and by that he doesn’t mean just stumbling and breathing through the world, but living as consciously as you can.”[21] This demanded not conformity to fashion but the unleashing of a sort of compassionate deviance. As if to bring the point home, “Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance” immediately segued into a reprise of “What’s the Ugliest Part of Your Body?” The song broke down in a glossolalia of voices chanting mind and body before a carnival barker announced, “Do it again! Do it again!” Then Zappa and band began the typewriter-staccato rhythms of the song “Mother People.”

Let me take a minute and tell you my plan

Let me take a minute and tell who I am.

If it doesn’t show, think you better know

I’m another person.

Here was a simple way forward from the truest, bluest, sunshine daydream of the Summer of Love. Zappa and the Mothers of Invention chanted, building up to the point of it all.

We are the other people

We are the other people

We are the other people

You’re the other people too

Frank Zappa may not have believed that all you need is love, but he was, despite the name of his album, in it for more than just the money. With satire as a powerful tool for weathering the tempest in a bong that was the Summer of Love, he too was ultimately in it for the long-term goal of getting by with a little help from your friends.

The Mothers of Invention, “Who Needs the Peace Corps?”

The Mothers of Invention, We’re Only In It For The Money full album

Notes

[1] The Beatles, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Capitol Records, 1967). Richard Poirier, “Learning From the Beatles,” Partisan Review, Fall 1967, 526-546; Benjamin Demott, “Rock as Salvation,” New York Times Magazine, 25 August 1968, 30; in the New York Times, Kenneth Tynan infamously called the album “a decisive moment in the history of Western civilization,” as quoted in Ian MacDonald, Revolution in the Head: The Beatles Records and the Sixties (1994; reprint, Chicago Review Press, 2005), 249. These are just a few of the many positive, even euphoric responses to Sgt. Pepper in 1967. By 1973, musicologist Wilfrid Mellers would compare the band to Beethoven; see Mellers, Twilight of the Gods: The Music of the Beatles (London: Faber & Faber, 1973).

[2] Paul Kantner of Jefferson Airplane describes this phenomenon in the Haight; see Brendan M. Stewart, “The Beatles: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” 27 August 2014, https://shabby-road.com/2014/08/27/the-beatles-sgt-peppers-lonely-hearts-club-band/. I believe Kantner mentions this fact in various documentary film interviews.

[3] Richard Goldstein, “We Still Need the Beatles, but…,” New York Times, 18 June 1967, 24D.

[4] Barry Miles, Hippie (New York: Sterling, 2004), 260; “Weir recalls the Grateful Dead’s Summer of Love and Haight,” Goldmine, 31 October 2001, http://www.goldminemag.com/articles/weir-recalls-the-grateful-deads-summer-of-love-and-haight.

[5] Devin McKinney, Magic Circles: The Beatles in Dream and History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 187, 183.

[6] The Mothers of Invention, We’re Only In It For the Money (Verve Records, 1968).

[7] Zappa’s Adorno-esque qualities eventually inspired the British writer Ben Watson to write a critical theory-style treatise on his art and career, Frank Zappa: The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995).

[8] David Walley, No Commercial Potential: The Saga of Frank Zappa (1972; updated edition, New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), 12-71.

[9] See Ehrhard Bahr, Weimar on the Pacific: German Exile Culture in Los Angeles and the Crisis of Modernism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

[10] Dave Hickey, “Freaks,” in Air Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy (Los Angeles: Art Issues. Press., 1997), 88-95. Steve Silberman, “Freak vs. Hippie, for Dario,” Listserv message, 26 July 1996, https://gopherproxy.meulie.net/nemesis.cs.berkeley.edu/00/miscellaneous/freak-vs-hippie.

[11] Quoted in Alice Echols, “Hope and Hype in Sixties Haight-Ashbury,” in Shaky Ground: The ’60s and Its Aftershocks. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 30.

[12] The Mothers of Invention, Freak Out! (Verve, 1966) and Absolutely Free (1967).

[13] Joel Selvin, Summer of Love: The Inside Story of LSD, Rock & Roll, Free Love and High Times in the Wild West (New York: Dutton, 1994), 38-39; Zappa – 1966 Fillmore Auditorium, SF, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7P_xkb6QEJM.

[14] Walley, 71-85. Among other infamous stunts at the Garrick, Zappa had a group of Marines sing Bob Dylan’s “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35,” with its chorus “everybody must get stoned,” before violently ripping apart baby dolls on stage.

[15] Walley, 89-94.

[16] Scott MacKenzie, “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)” (Columbia, 1967). For the full story on the Monterey Pop Festival, see Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik, A Perfect Haze: The Illustrated History of the Monterey International Pop Festival. (Santa Monica, CA: Santa Monica Press, 2011) as well as The Complete Monterey Pop Festival, dir. D. A. Pennebaker (film originally released in 1968; DVD, Criterion Collection, 2002).

[17] Ben Fong-Torres, “Harrison had love-Haight relationship with S.F.,” San Francisco Chronicle, 2 December 2001, http://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/radiowaves/article/Harrison-had-love-Haight-relationship-with-S-F-2847011.php.

[18] Quoted in Bill Graham and Robert Greenfield, Bill Graham Presents: My Life Inside Rock And Out (New York: Doubleday, 1990), 195.

[19] Grateful Dead, “Uncle John’s Band,” Workingman’s Dead (Warner Brothers, 1970).

[20] Thomas Frank, The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture and the Rise of Hip Consumerism (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

[21] Dave Marsh, “Are You Hung Up?” Rock & Rap Confidential 126 (August 1995), reprinted in Richard Kostelanetz, ed., The Frank Zappa Companion: Four Decades of Commentary (New York: Schirmer Books, 1997), 53-54.

11 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Great reading of Zappa versus the Beatles — I have a new respect for Zappa after reading this.

Great piece! Zappa wasn’t more famous/popular than Jesus, he was Jesus!

Really enjoyed this piece on Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention! I’m more familiar with his critique of consumer culture in the 1970s and 1980s, so this was a revelation for me. If anything–and you allude to this in the latter half of your essay–do you think the critiques Zappa lobs at the Summer of Love continue on through the rest of his career as he targets other parts of mainstream society?

Fantastic essay and very good reading. I used the contrasting perspectives of Phillips/ McKenzie and Zappa’s views of San Francisco in my thesis as well. Would you see Zappa being from LA and not San Francisco as important to his critique of the Summer of Love in the Haight?

Robert — Absolutely, even on We’re Only In It For the Money, Zappa is as critical of the repressions of mainstream America, as he saw them, as he is of the Summer of Love response to it, and his deep suspicion and distrust of both continued into the 1970s so far as I can hear it. Maybe it got a bit more cartoonish by the late 1970s? I sort of hear more exasperation in his sound. But then in the 1980s he was very committed to the anti-censorship movement against Tipper Gore and company, so that was much less cynical.

Kevin — Yes, good point. I think that the LA (outer LA really) perspective made Zappa way less idealistic than the SF participants, who had the traditions of Bay Area bohemia to root themselves in/blast off from.

Thanks for the reply! That makes a lot of sense.

Blast off from… That is actually a very accurate term. I like how you state this as “less idealistic” because I think that really explains Zappa well. Thanks for the response!

What a fun, brilliant dissection of Zappa! I’ve always been more attracted to the negativity / nihilistic aesthetics of the likes of the Velvet Underground and the Stooges, but this definitely makes me rethink the history of 60s rock and roll differently.

So how does Zappa’s satire translate into a social or political vision, if it actually does? I know that there is still an invocation of a “we” and “otherness”, but how can we (again, if we can) link these constructions to the sociopolitical culture and ideas of the time? Or are we in the world of the the negative community, a community always displaced through the aesthetics / ethics of negativity?

Thanks Kahlil!

My sense is that it’s far more the kind of “negative community.” Zappa really was sort of the Adorno of rock in this way. But I wonder this…maybe we might look to the music for a different kind of affirmative dimension in Zappa’s message? In the virtuosity? In the ensemble’s interplay? Zappa was a notorious task master with his bands so they were not the kind of egalitarian community one idealizes with say, The Beatles, but…there is a kind of affirmation there of a way in the musical creations (bandmates, producers, collaborators): **we** are a group, in it together, trying to make this massive electric ensemble sound experiment work, synchronizing and syncopating our efforts. So maybe the musical process offers an affirmational community, but Zappa always wants to guard against (using critique, sarcasm, humor, absurdity) any kind of cheaply achieved communal we. For him, that’s a false god. But you can only have false gods if you still believe true ones are out there, too, I suppose. And that’s what distinguishes Zappa from just being a cynic. Well, that’s my take on the matter. Great question!

A great piece, Michael. At this time, Zappa was completely tuned into the dichotomies of the sixties. The road manager of the Sons Of Champlin, a rightly legendary figure named Charlie Kelly (google him, you’ll see), has commented that he actually lived “Let’s Go To San Francisco.”

“In 1968 I ran away with a circus called the Sons of Champlin, and I didn’t return until nine years later. The idea of traveling with a rock band was sufficiently romantic at that time that Frank Zappa had already released a song which contained the lyrics, “I will go to San Francisco. I will join a band and become the road manager. I will sleep on floors and catch the crabs and smoke an awful lot of dope.” Zappa captured the San Francisco feeling perfectly, even though he was probably trying to satirize it.”

http://sonic.net/~ckelly/Seekay/sons_page1.htm

I never saw zappa better than when he played the bicycle on the steve allen show.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1MewcnFl_6Y