Note to readers: This essay by Kevin Mitchell Mercer is the first of five guest essays in our Summer of Love roundtable. Kevin Mitchell Mercer is an adjunct professor of history at the University of Central Florida. His recently completed master’s thesis focuses on the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco and geographic theories of place and space.

The Houseboat Summit: A Countercultural Vision for a Utopian Drop-Out Society

By Kevin Mitchell Mercer

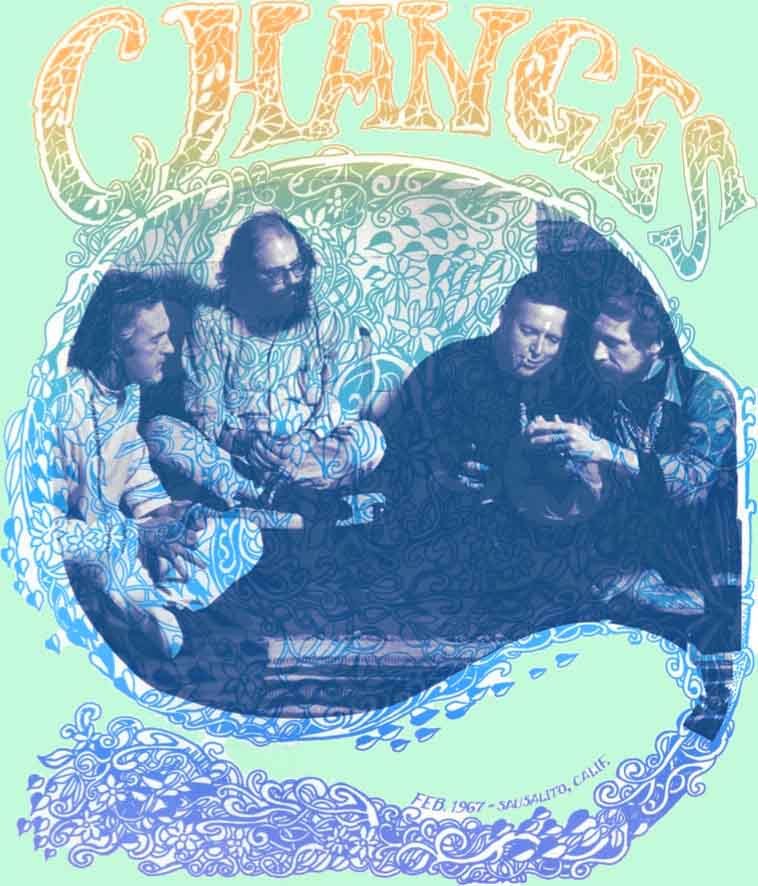

The San Francisco Oracle, the prominent Haight-Ashbury underground newspaper, dedicated a major part of its seventh issue in February, 1967 to a conversation between countercultural luminaries Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg, Allan Watts, and Gary Snyder. The four men, along with Oracle publisher Allen Cohen and a small gathered audience met on Watts’ converted ferry, the Vallejo, moored in Sausalito, California. Coined “The Houseboat Summit,” the entirety of their conversation was transcribed within the pages of the psychedelic newspaper. The rambling dialog articulates the men’s vision for the developing hippie counterculture of the late 1960s.

The men, despite their various backgrounds, had attached themselves to the emerging counterculture rooted in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district. Ginsberg and Snyder were both notable Beat poets. Leary held a PhD in psychology and had until 1963 taught at Harvard University. His experimentation with psychedelics, like the drug known as LSD, had led to his removal form the faculty there. Watts had been an Episcopal priest until 1950, he held a master’s degree in theology, and at the time of the summit was working for American Academy of Asian Studies while publishing popular books on eastern religions. They were all connected through friendship in one way or another and shared a belief in the promise of psychedelics being part what they saw as a larger spiritual awakening.

The men, despite their various backgrounds, had attached themselves to the emerging counterculture rooted in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district. Ginsberg and Snyder were both notable Beat poets. Leary held a PhD in psychology and had until 1963 taught at Harvard University. His experimentation with psychedelics, like the drug known as LSD, had led to his removal form the faculty there. Watts had been an Episcopal priest until 1950, he held a master’s degree in theology, and at the time of the summit was working for American Academy of Asian Studies while publishing popular books on eastern religions. They were all connected through friendship in one way or another and shared a belief in the promise of psychedelics being part what they saw as a larger spiritual awakening.

The meeting occurred after the successful Human Be-In, which had brought 30,000 young people to Golden Gate Park for what had been termed at the time as a “gathering of the tribes” in January, 1967. The substantial media coverage of the event acted as an impetus for young people from around the country to join up with the San Francisco hippies, culminating with the Summer of Love later that year. During this period between the Human Be-In and the Summer of Love numerous elements within the hippie underground sought to define the tenets of the new community to themselves, the young new arrivals, and the curious media. Collectively, the men involved with the Houseboat Summit set forth their personal visions for a psychedelic utopia. To this end, their conversation was dominated by the fundamentals and realities of dropping out, the importance of decentralized tribalism, and the practices of hippie spirituality.

In what would later become a slogan for a generation, Leary told the young people assembled at the Human Be-In to “tune in, turn on, and to drop out.” It was the latter part of this phrase that drew attention during the Houseboat Summit. Leary sought to clarify the ideas of dropping out while in conversation with Ginsberg, Snyder, and Watts. Put simply, dropping out was meant to signal a removal of oneself from the institutions of modern society. We might call it “going off the grid” today. The burgeoning counterculture provided a supportive community in the 1960s for one when they sought this drastic exit. In the context of an urban space, a network existed to provide food, housing, and temporary jobs for young people. The group saw cities as way stations, places to allow hippies to coalesce. To quote Leary, in “a place like Haight-Ashbury. There they will find spiritual teachers, there they will find friends, lovers, wives…”[1] As people would drop out in stages, this would be a formative but temporary middle point of as people began their self-imposed removal from modern society.

Despite the idealism of the overall conversation on dropping out, the men did discuss the practical application of such an action. Ginsberg challenged Leary on the development of Millbrook, a historic mansion in New York that he operated as a kind of communal psychedelic drug laboratory. Despite no longer being associated with Harvard University, Leary was actively fund-raising, lecturing, and campaigning on the positive psychological impacts of LSD.[2] While the conversation shifts away from Ginsberg’s charge, Leary later advocates for dropping out slowly and purposely.[3] As Ginsberg and Leary were friends, the exchange is polite, but it highlighted the challenge of putting word to action as well as what dropping out really means in practice. Leary, while advocating for people to drop out, was himself still deeply and actively engaged in both the political and financial aspects of contemporary society.

Part of achieving a dropout psychedelic utopia, as articulated by Ginsberg, Leary, Watts, and Snyder, called for a return to a kind of tribal primitivism. As Snyder saw it, there were three spaces; wilderness, rural, and urban. Those dropping out would naturally form into bush tribes, farm tribes, and city tribes.[4] The tribal identify stems from the challenging idealism most countercultural participants placed upon Native Americans. By dropping out into small tribal groups, the men suggested decentralization and the use of social structures established by Native Americans, while at the same time employing native knowledge for survival. Overall, the men’s view of Native Americans and tribal societies in general was naïve and simplistic.[5] Their prescription for the challenges of modern society was simply to reverse ideas of progress in a return to primitivism.[6]

As the summit’s conversation progressed, ideas of tribalism broke down into smaller clan and extended family group concepts. It is here that the men added group marriage to the conversation. It is through this clan structure and group marriage that they argued capitalist civilization would evaporate in the face of a family based collectivism. These ideas are presented as a contrast to contemporary familial and educational institutions. While sincerely articulated, the realities a communal anarchist shift in society are not supported with practical measures but through a belief in a spiritual enlightenment through psychedelics. Snyder articulated this historical moment as society turning a corner; “It’s a bigger corner than the Reformation, probably. It’s a corner on the order of the change between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. It’s like one of the three or four major turns in the history of man.”[7] The group agreed, largely seeing the reordering of society through a return to native primitivism and a spiritual reawakening through psychedelic drug use.

All four men self-identified as spiritual leaders of one cloth or another, so spirituality and the importance of religious teachers was another critical element of the Houseboat Summit and their collective vision of a utopian future. Responding from comments from the audience, Snyder and Leary stressed the importance of spiritual leadership and meditation centers. In-line with hippie thinking and the assembled group, these centers would teach from a buffet of the world’s religions. Ginsberg had previously referred to the young hippies drawn to the Haight-Ashbury district as “young seekers.”[8] These mystical meditation centers reflected that idea of seeking that dominated hippie spirituality.

This loose confederation of spiritual ideas defined many of the gurus within the Haight-Ashbury scene. The conversation here supports that blending of the exotic and mundane. Considering Watts extensive religious background, the expectation would be that his knowledge would dominate the conversation when it turned to religion. While Watts does add his considerable knowledge, it is again Leary and Ginsberg who dominate the conversation, this time with surface level religious imagery of Hinduism and Buddhism. Just as they had done with Native American ideology in their conversation of primitivism, the groups cursory understanding of spirituality missed crucial aspects of the world’s major religions, allowing them to be folded into psychedelic drug use for a superficial spirituality.

The Houseboat Summit is problematic for a number of reasons. First, and most important, Ginsberg, Leary, Snyder, and Watts are all male and generally a decade older than the average young person involved with the hippies of the Haight. At the time of the meeting Ginsberg was 41, Leary 47, Snyder 37, and Watts 53 years old. Second, while these types of conversations were common for this group of friends, this one was published by The San Francisco Oracle. These two factors, combined with the celebrity of the men involved means the conversation reeks of the patriarchy that dominated the society they advocated dropping out of. Additionally, the publication of the conversation allows it to become a set of well-read rules and dogma aimed at a leaderless youth-based social revolution. The men were aware of some of these critiques. Their role as leaders of the Human Be-In came up during the Houseboat Summit, in response Ginsberg responded in a self-aware tone as he discussed the accusation that he had been a leader; “What were WE doing up on that platform?” While Leary responded “That’s a charge that doesn’t bother me at all.”[9] Interestingly, it is within this exchange that an anonymous voice from the audience defends the men, twice, just as they were tried to openly engage the criticism.

The Summer of Love put extreme pressure on the counterculture movement in the Haight-Ashbury. The massive influx of over 100,000 people into the neighborhood created a public health crisis. This, along with other factors, pushed many of the hippies to smaller urban centers or rural communes after 1967. Many of the ideas articulated during the Houseboat Summit and broadcast in the pages of the Oracle would in their own way come to pass. Some elements of the countercultural became increasingly communal and spiritual, but a psychedelic utopia would never become reality. The sincerity of Ginsberg, Leary, Watts, and Snyder are difficult to judge, but their eagerness to attach themselves and their celebrity to the counterculture unintentionally circumvented a grassroots social insurgency. Through patriarchy and celebrity, the weight of their ideas should be seen less as a summit and more at an attempt to place leadership and dogma into a revolution that sought to avoid both.

_________________________________

[1] “Changes,” The San Francisco Oracle, February, 1967, 7.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 9.

[4] Ibid., 12.

[5] For more on the relationship between the counterculture and Native Americans, see: Phillip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999) and Sherry L. Smith, Hippies, Indians, and the Fight for Red Power (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

[6] Theodore Roszak, The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969).

[7] “Changes,” The San Francisco Oracle, February, 1967, 32.

[8] George Dusheck, “’They’re Young Seekers, not Hippies,’ Say Poet Ginsberg,” San Francisco Chronicle, January, 22, 1967.

[9] “Changes,” The San Francisco Oracle, February, 1967, 15.

_______________________

Kevin Mitchell Mercer is an adjunct professor of history at the University of Central Florida. His recently completed master’s thesis focuses on the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco and geographic theories of place and space.

11 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This is a great first part of the roundtable. I’m curious: are you (or is anyone else) aware of any serious pushback from Native Americans to the way their history and culture was conceptualized by the people at the Houseboat Summit?

Yeah. So the shortest answer is “it’s a very complicated relationship” … I presented a paper on the 1969 Native American occupation of Alcatraz a few years ago. The thought on the island at the time was self-determination, so they took donations from hippies and left activists, but they didn’t allow them on the island. There was a fear that any non-Native American presence would shift the meaning of the occupation. On the flip side, a few scholars have pointed to the fact that hippie- Native American interactions, despite all their challenges, did bring awareness to the desperate poverty on reservations and put Native American issues into the consciousness of the American public. I highly recommend both Deloria and Smith (cited above) if you want to explore the idea more.

Thanks for the question Robert!

And thanks for the quick answer! Again, really enjoyed the post.

At the recent Revisiting the Summer of Love, Rethinking the Counterculture conference (http://www.engage.northwestern.edu/sfconference/schedule-detail/), Sherry Smith gave a powerful presentation, based on her book research, about how Native American activists pragmatically harnessed the young white hippie interest in them culturally for political struggles for increased self-determination. This was at the Alcatraz protests in San Francisco. To be sure, both the “elders” such as the Houseboat Summit participants and younger “seekers,” as Ginsberg called them, appropriated Native American culture to try to make sense of alternatives to mainstream Cold War American life; but out of those often careless, clueless appropriations emerged a number of strong affiliations and solidarities. Which is not to say, as Smith readily noted, that the political organizing did not take place within fraught, problematic cultural interactions. Rather, the irony was that the appropriations had surprising dimensions, according to her research.

Fascinating stuff, I wish I’d seen the “call for papers” for this one, and still scratching my head wondering how I missed it.

Kevin,

I’m curious to hear more of your perspective on two things:

1) the tensions among the speakers at the Houseboat Summit. As I recall Ginsberg and Snyder (who was always ambivalent about, if not resistant to, being called a Beat poet) really question a lot of Leary’s perspective.

2) the perspective put forward at the Summit about the recovery and resurgence of artisanal labor and work. Am I recalling correctly that Snyder makes a big point about this: his version of Brautigan’s “All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace” vision of automation combined with a world of craftspeople and artisans living in more rooted ways?

Thanks,

Michael

Michael,

Snyder has always been a curveball for me, I think you are right about him never identifying as a Beat, and I also probably oversold his status as a “self-identified spiritual leader.” He was however part of Kerouac’s “Dharma Bums” novel, so I may have taken a liberty for the sake of being concise. I think there was a bit of tension between everyone and Leary in the fact that Ginsberg, Watts, and Snyder seem to be veterans of the “dropout” ideal that Leary both advocated for and claimed to be doing “step-by-step.” Snyder and Leary get into it about the fact that simply “dropping out” isn’t enough but you have to build something. Leary at this point seems to get defensive and get really abstract. Snyder and Leary’s debate early in the Summit seems to set a tone for the conversation moving forward that forces them all to put practical application to the abstract points. So to your first question, I think you are exactly right that Snyder does take Leary to task a bit early on in the conversation, and I think that shapes a lot of the dialogue moving on.

To your second question:

Snyder does go into a dialogue about automation. His idea is that automation plus psychedelics and the spiritual change that society will undergo with them will see a new leisure society. It was his idea that through this vision people will consume less and reproduce less voluntarily. The conversation quickly moves away from that idea into the neo-primitive ideas, and it is Snyder who actually talks about how this can actively be (re)learned. Snyder and Watts actually go on at length about living in a more rooted way and (re)learning the skills to live this way. Interestingly, Leary and Ginsberg both give theses ideas praise but don’t add much insight of their own about how these things can practically be done.

Thanks for the questions!

Interesting article Kevin. The Houseboat Summit is in some ways a seminal event in the counterculture evolution. It is important to note, as you already have Kevin, that all these guys were good friends, particularly Gary Snyder and Alan Watts. To that point Michael- and I enjoyed your presentations and participation at the recent Northwestern “Summer of Love’ conference- the tension at the Summit was mainly propagated by the frenetic energy Leary displayed in his desire to deliver a message touting casual and frequent LSD use as a lifestyle choice; Watts, who acted as moderator, and Snyder were not of the same opinion. In fact, Watts advocated using LSD sparingly and said, “when you get the message, hang up the phone.” Parenthetically, Leary was soon to be banned from the houseboat [owned by the Society of Comparative Philosophy which was founded by Watts and the “poet-warrior” Elsa Gidlow] by Jean Varda when he spiked the punch with LSD at a party there.