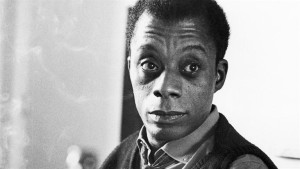

James Baldwin’s birthday of August 2 has come and gone, but I wanted to use today’s post to think about the place of Baldwin in American intellectual history. Previously at this website, we have discussed Baldwin in numerous ways—from using close reading to compare his work to that of Ta-Nehisi Coates, to talking about his impact on American liberalism and the ways in which he can be used as part of a classroom lesson. It would be a mistake, however, to not spend a moment thinking about how this writer has had such an out-sized influence on intellectual history since the early nineteen-sixties. At the same time, Baldwin’s works and arguments with other writers also bring into sharp relief other trends from modern American intellectual history.

His jousting with white conservatives and liberals alike serves as a reminder of the complicated politics of race—politics that we, of course, still live with today. The debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley at Oxford in 1965 is just the starkest example. That debate is worth watching, however, not just for seeing two influential figures debate each other, but remembering the cross-Atlantic currents within which the Civil Rights Movement existed. Think of Malcolm X’s own debate at Oxford the previous year,  Martin Luther King, Jr.’s various speeches in the United Kingdom (or for that matter, his forays into Canada

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s various speeches in the United Kingdom (or for that matter, his forays into Canada

and elsewhere

), and even Baldwin’s other speeches in Britain. From the moment he set foot in France in 1948, Baldwin thought about race from not just an American, but an international context too. Thankfully, in recent years work has not just been done on Baldwin in France and Switzerland—the traditional places thought about with Baldwin’s travels abroad—but also his numerous trips to Turkey as well. Placing American intellectuals in international context is something that we should keep in mind, especially with Baldwin’s Cold War-era and decolonization context.

Zeroing in on Baldwin’s writings and interviews for a second, I cannot also but help think about the 1968 interview he did shortly after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. for Esquire

magazine. The death of King hit Baldwin hard—as it did many black Americans, regardless of their fame or political power. In “How to Cool It,” Baldwin’s answers remind us all of the troubled place race relations held in the American psyche during 1968. Considering that the release of Detroit this week has historians looking back at a seminal racial conflagration, and keeping in mind modern concerns about black lives mattering the precarious state of voting rights, affirmative action, and immigration, Baldwin’s answers would not seem out of place in a modern interview. I have no right to speak for Baldwin. And I abhor putting words in the mouths of those who’ve been long gone. But Baldwin stating, “It is not for us to cool it,” at the start of the interview seems like the perfect phrase to describe our modern discord.

Baldwin’s interview is also fascinating to read for his denunciation of the War on Poverty, which he felt had not gone far enough. Baldwin’s intersectionality—seeing the complicated nature of race, class, gender, and sexual orientation in American life—means that intellectual historians have so much left to mine from his work. As a person who focuses on the American South, I am also intrigued by his writings on regionalism, north and south, in the United States. I could, of course, keep going, but with Baldwin’s birthday only a few days ago—and our “Summer of Love” roundtable about 1967 just coming to an end—I want to launch a discussion in the comments about what Baldwin means to American intellectual history. The shadow of James Baldwin looms over America, now more than ever.

9 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for the post and the links Robert. I had forgotten that he was such a mesmerizing public speaker.

Not a problem! I think it’s incredible that there are so many examples of Baldwin’s public speaking freely available online. Thanks for reading.

To hear and see Baldwin speak takes his rhetorical skill to whole other level. Mesmerizing. Thank you.

Completely agreed!

I enjoyed this short piece. Nice to be reminded of Baldwin’s trips to Turkey and the international context always entangling USIH. (plus, it is always good to have an excuse to watch that Baldwin-Buckley debate). Thanks.

Thank you for this, Robert Greene II. I wonder if anyone else watching the 1965 Baldwin-Buckley debate noticed the fact that the cameraman, for a significant portion of the time during Baldwin’s remarks, zoomed in to a close up of just his face, whereas during the Buckley remarks, he almost never did. It seems that Baldwin has been disembodied so that all that remains is his blackness whereas Buckley enjoys the privilege of having his identity as a member of a civilized besuited community reaffirmed throughout via a camera position that captures his similarity to the majority behind him. His whiteness is subsumed into the civilized while Baldwin’s blackness becomes the essence of his identity.

Beyond such framing, I also found it striking that Baldwin referenced Bobby Kennedy’s prediction that a black man could be president in 40 years, a prediction that turned out to be prescient, and which would seem to vindicate its speaker in spite of Baldwin’s sharp attack on the pronouncement.

As for Buckley’s remarks, the one that stands out is his comment that in 1965 race relations was a topic overshadowing all other public policy debates in the United States. What he didn’t articulate was the potential such a situation has to yield blowback, in the form of resentment that other pressing social problems are not being demonstrably addressed, and ultimately slow down the cause at hand. One is tempted to wonder if the same phenomenon was at work during the 2016 election cycle, given the heightened attention to race relations that characterized the latter half of the Obama presidency.

And finally, a question for USIH readers. Baldwin at 32 minutes lays the dawn of the post WWII civil rights movement in the United States on the increasingly visible role that Africa began to play on the world stage during the Cold War. Is there a definitive work that traces the linkages between a new international relations paradigm that includes Africa (its statesmen, dictators, diplomats, and tyrants) and the rise of the civil rights movement? If so and someone could share I would be most grateful.

First off, thanks for your great comments! Second, to address your question about the links between civil rights and international affairs, here’s a few:

1) Thomas Borstelmann, “The Cold War and the Color Line.”

2) Mary L. Dudziak, “Cold War Civil Rights.”

3) Penny Von Eschen, “Race Against Empire: Black Americans and Anticolonialism, 1937-1957.”

4) Nikhil Pal Singh, “Black is a Country.”

Those are some good places to start, and of course others can add to the list too! Happy reading.

I also watched the Buckley-Baldwin debate (a few days ago), which I had not seen before. I had a couple of reactions that differ a bit from Moss Reumann’s in the interesting comment above.

There were two moments in Buckley’s presentation that struck me the most. One was his citing of Nathan Glazer toward the end (would take too long to detail this, but I found it weird and, like most of what Buckley said, unconvincing — for one thing, Glazer, at least for the particular point Buckley cited, ignored the different historical circumstances faced by African-Americans in the U.S. as opposed to other minority groups).

Second was Buckley’s response to the questioner from the floor who asked, in effect, what justification was there for not allowing blacks to vote in Mississippi, to which Buckley’s response was that the problem in MS was not that too few blacks were allowed to vote but rather that too many whites were allowed to vote. This was greeted with laughter, but it’s not at all clear, esp. given what I take to have been Buckley’s basic views and impulses, that he was joking.

Like Reumann, I noted Baldwin’s reference to RFK’s prescient prediction. I thought Baldwin’s speech was effective partly because he was able to bring the authority of autobiography, of personal witness, to some of his points. There are different sorts of debates; this one struck me as a duel of worldviews rather than a duel of two tightly organized lawyer’s briefs, so to speak.

First off, I think your point about Buckley possibly not joking in response to the question about Mississippi is important.

As for the debate itself, you make a good case that it really was a clash of worldviews. They’re worldviews that we have yet to fully reconcile–and, perhaps, it’s not really possibly to reconcile them at all.