Note to readers: This essay by Lilian Calles Barger is our third installment in the Summer of Love Roundtable. (You can read previous installments here and here.) Lilian Calles Barger is an intellectual, cultural and gender historian and an independent scholar. Her book The World Come of Age: Religion, Intellectuals and the Challenge of Human Liberation is forthcoming from Oxford University Press. She is currently researching the history of feminism and the gender revolution.

Hippie Chicks: A Different Feminism

By Lilian Calles Barger

Etched into the nation’s cultural memory are the Summer of Love and the Haight-Ashbury area of San Francisco, carrying with them images of free love, psychedelics, and rock and roll. The year was 1967, when over 100,000 young people rejected their parents’ lifestyle and flocked to San Francisco, stopping in places like Taos, Flagstaff, and Tucson on their way to join Timothy Leary and “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” Their story of breaking through the limits of conventional society produced what we call the counterculture, and it still reverberates 50 years later. From our historical vantage point, the counterculture that emerged that summer marked the death of The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1955) and Fascinating Womanhood (1963) and the beginnings of a gender revolution. The summer’s intellectual and cultural history has largely focused on the men who seeded it with ideas; they included Leary, Jerry Rubin, Paul Goodman, Richard Alpert (aka Ram Dass), Stewart Brand, and Allen Ginsberg. But, just as the overgrown branches of the counterculture are still evident 50 years later, so too its roots extend back to the early 20th century, during a migration from the East Coast to the far reaches of the West in which women led the way.

Women of the counterculture, who were often cultural creators in their own right, figure less prominently within the history of the counterculture or that of feminism. Recurring images of that hot summer include a young, guitar-strumming Joan Baez, who actually left her music career in the 1960s to devote herself to antiwar activism. Her participation in the 1968 group photo captioned “Girls say yes to boys who say no” will forever be an icon of the antiwar movement. The other woman in our cultural memory of the time is Janis Joplin, an awkward middle-class girl from Port Arthur, Texas, who turned herself into a rock/blues songwriter and singer and became immortal after her early death by a heroin overdose. Joplin was strong and unapologetically loud, and I can still hear her singing “Piece of My Heart,” expressing the opposite of the demure ladylike norms of the postwar American woman. To many women of her generation, “Janis,” the original hippie chick, became the embodiment of a self-possessed feminism. Neither Baez nor Joplin shows up prominently in the history of modern feminism, however.

Women of the counterculture, who were often cultural creators in their own right, figure less prominently within the history of the counterculture or that of feminism. Recurring images of that hot summer include a young, guitar-strumming Joan Baez, who actually left her music career in the 1960s to devote herself to antiwar activism. Her participation in the 1968 group photo captioned “Girls say yes to boys who say no” will forever be an icon of the antiwar movement. The other woman in our cultural memory of the time is Janis Joplin, an awkward middle-class girl from Port Arthur, Texas, who turned herself into a rock/blues songwriter and singer and became immortal after her early death by a heroin overdose. Joplin was strong and unapologetically loud, and I can still hear her singing “Piece of My Heart,” expressing the opposite of the demure ladylike norms of the postwar American woman. To many women of her generation, “Janis,” the original hippie chick, became the embodiment of a self-possessed feminism. Neither Baez nor Joplin shows up prominently in the history of modern feminism, however.

Many of these musicians’ fans, ordinary women who joined the counterculture aspiring to take a trip to a more bucolic setting, remain caught in a historiographical fault line between Ruth Rosen’s liberal The World Split Open (2000) and Alice Echols’ Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967–1975 (1989); they are considered to have been bypassed by the women’s movement. The hippie chicks of the counterculture have received little attention in the history of feminism, having been swallowed up by the history of a male-dominated “back to the land” movement, the sexual revolution, and the La Leche League.

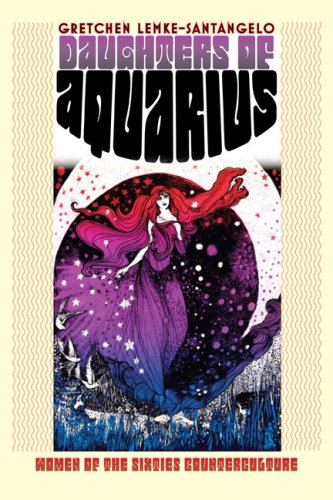

Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo’s Daughters of Aquarius: Women of the Sixties Counterculture (2009) is the only monograph to date that has given these women a place in the history of feminism. Instead of portraying them as stereotypical earth mothers, nymphs in peasant dresses, or strung-out domestic drudges—the antithesis of feminism—the author demonstrates how these women broke with both the middle-class housewife and the rising career woman to recover the value of women’s productive labor in rural America. They rejected both liberal feminism’s insistence on state-guaranteed rights and radical feminism’s rejection of gender binaries to forge their own version of female empowerment.

Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo’s Daughters of Aquarius: Women of the Sixties Counterculture (2009) is the only monograph to date that has given these women a place in the history of feminism. Instead of portraying them as stereotypical earth mothers, nymphs in peasant dresses, or strung-out domestic drudges—the antithesis of feminism—the author demonstrates how these women broke with both the middle-class housewife and the rising career woman to recover the value of women’s productive labor in rural America. They rejected both liberal feminism’s insistence on state-guaranteed rights and radical feminism’s rejection of gender binaries to forge their own version of female empowerment.

Lemke-Santangelo demonstrates how hippie women contributed to a developing cultural feminism. She unpacks the gender ideology of the counterculture, rife with assumptions of women as being intuitive, nurturing, cooperative, and ruled by the cycles of their bodies and emotions. Counterculture women embraced these values and turned to them as a source of power, sharing this viewpoint with cultural feminists emerging in urban consciousness-raising groups. The differing moral sensibility that counterculture feminists embraced would later become the “ethics of care” defined by Carol Gilligan’s In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development (1982).

Rather than seeing the essentialist view of women as a liability, many counterculture women claimed their power through the creation of “woman-centered” spirituality and sexuality, in which a return to the land, an often unrealized ideal, communal living, and simple practices unseen since the 19th century offered possibilities for self-definition. Alongside men whose intransigent sexism remained very much like that of their fathers, women in rural communes took on the burden of the strenuous work and caregiving, revaluing women’s traditional productive labor, which had been superseded by industrialization. Freed from the chains of an office desk and breaking through the picket fence of suburbia, they gained confidence in their hard-won domestic and farming skills to assert the value of female difference. They banded together to rediscover skills in organic gardening, bread baking, keeping chickens, home remedies, midwifery, and nearly lost arts and crafts. Counterculture women appropriated Eastern and Native American practices such as sweat lodges, folk medicine, and spiritual rituals. Orchestrating the rebuilding of communal life, often ahead of the men, women rejected industrial food and the consumer culture that defined the lives of their mothers as a revolutionary act toward greater human well-being. Hippie women were also unlike the generations in their recent memory in developing a flexible lifestyle that allowed greater sexual expression and freedom, spiritual and psychedelic experimentation, and a sense of economic power that generated a feminist consciousness.

By the early 1980s, as counterculture communities declined owing to pressure from within and without, many women reentered the mainstream, becoming social entrepreneurs who spread the gospel of holistic medicine, yoga, natural childbirth, breastfeeding, organic foods, and homeschooling. Their heirs continue to live the ethos of cultural feminism that values female difference and asserts its power.

Living in Taos, I have had the chance to meet the feminist daughters and granddaughters of the counterculture that flooded the scarcely populated county in the late 1960s. The Summer of Love and subsequent years brought a “hippie invasion” to Taos. Society’s “dropouts,” with flowers in their hair and utopian dreams, were attracted by cheap land, Indian mysticism, and the area’s history as an artists’ colony. “Trustafarians,” as hippies were often called for their occasional reliance on daddy’s money, bought parcels of cheap land and built communal farms with names such as Magic Tortoise, Hog Farm, and the Lama Foundation (which is still in operation), an interspiritual community where Ram Dass frequently held seminars on Eastern and Jewish mysticism. While rejecting mainstream American life, they attempted to build new institutions by founding a monthly paper, The Fountain of Light; an alternative school called Da Nahazli; and a health food store. Life included sexual experimentation, drugs used for the purpose of spiritual enlightenment, and parental neglect in the form of a freewheeling child-rearing philosophy. And yes, life was fraught with problems for women. Free love often resulted in abuse, unwanted pregnancy, and women’s abandonment by their partners, leaving some to survive on welfare checks or eke out a living on unproductive land in communities where they were unwelcome. The newly arrived hippies were considered dirty and often lived without plumbing in ramshackle structures, bringing STDs and drug use to rural communities. They were resisted by many traditional New Mexican Hispanic people, for whom religion and old family connections were revered. In time, some hippies settled in for the long haul, finding ways to coexist and changing both themselves and their adopted community. Most abandoned their unconventional lifestyle by the early 1980s, returning to the mainstream of jobs and mortgages.

But there is another story to the counterculture highlighting the role women played in the creation of not only an alternative way of life but also an alternative feminism. This story links the counterculture to the early 20th century. Lois Palken Rudnick’s Mabel Dodge Luhan: New Woman, New Worlds (1984) and Utopian Vistas: The Mabel Lodge Luhan House and the American Counterculture (1996) offer a history of Luhan and her long influence in creating and attracting the counterculture to Taos. Mabel Dodge was a runaway New York socialite, art patron, writer, and salon hostess who migrated to Taos in 1917 with her third husband, the modernist painter Maurice Sterne, and Elsie Clews Parsons, living there until her death in 1962. In New York City, she was a member of the feminist Heterodoxy club and heralded as the embodiment of the “New Woman” daringly liberated from the sexual mores of the time. Her westward journey from the glamor of upper-crust parties to the dusty roads of New Mexico was a search for an authentic way of life she found impossible within the constraints of conventional society. Hosting her bohemian friends, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Mary Foote, and Willa Cather, and drawing a multitude of now famous artists, writers, and musicians to New Mexico, Dodge sought an alternative for women of her social standing who never seemed to overcome the feeling that a woman fulfilled her innate purpose only through a man. She often imagined herself as a creative muse for men, such as her friend D.H. Lawrence. Dodge’s search for deep spiritual connections led her to consider the Taos Pueblo Indians as a true community in harmony with the cosmos and nature. This outlook was one America needed to embrace, she believed. Her desire to meld with Indian ways grew into love and a marriage to her fourth husband, a Tiwa Indian named Tony Luhan. She experienced her own Summer of Love in the sexual union with Luhan, which she believed melded the spiritual impulses of Anglo and Native American cultures.

But there is another story to the counterculture highlighting the role women played in the creation of not only an alternative way of life but also an alternative feminism. This story links the counterculture to the early 20th century. Lois Palken Rudnick’s Mabel Dodge Luhan: New Woman, New Worlds (1984) and Utopian Vistas: The Mabel Lodge Luhan House and the American Counterculture (1996) offer a history of Luhan and her long influence in creating and attracting the counterculture to Taos. Mabel Dodge was a runaway New York socialite, art patron, writer, and salon hostess who migrated to Taos in 1917 with her third husband, the modernist painter Maurice Sterne, and Elsie Clews Parsons, living there until her death in 1962. In New York City, she was a member of the feminist Heterodoxy club and heralded as the embodiment of the “New Woman” daringly liberated from the sexual mores of the time. Her westward journey from the glamor of upper-crust parties to the dusty roads of New Mexico was a search for an authentic way of life she found impossible within the constraints of conventional society. Hosting her bohemian friends, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Mary Foote, and Willa Cather, and drawing a multitude of now famous artists, writers, and musicians to New Mexico, Dodge sought an alternative for women of her social standing who never seemed to overcome the feeling that a woman fulfilled her innate purpose only through a man. She often imagined herself as a creative muse for men, such as her friend D.H. Lawrence. Dodge’s search for deep spiritual connections led her to consider the Taos Pueblo Indians as a true community in harmony with the cosmos and nature. This outlook was one America needed to embrace, she believed. Her desire to meld with Indian ways grew into love and a marriage to her fourth husband, a Tiwa Indian named Tony Luhan. She experienced her own Summer of Love in the sexual union with Luhan, which she believed melded the spiritual impulses of Anglo and Native American cultures.

The “ethnophilia” for the Indian way of life initiated by Dodge Luhan continued with the hippie invasion of the 1960s. A motorcycle-riding Dennis Hopper bought Luhan’s Taos home in 1970 becoming an artsy haven and crash pad for his iconoclastic friends. Dodge Luhan still serves as a feminist heroine to many Anglo-Americans, who celebrate her for both her art patronage and her daring lifestyle. As with the hippies of the counterculture, her story is a mix of deep yearning, unfulfilled dreams, and naiveté about a return to Eden. Her evolving feminism, sexual experimentation, primitivism, idealization of Indian religion (including “cultural appropriation” of local traditions, which resulted in resentment expressed toward her by Hispanics for redefining sacred santos as objects of art) make her a fitting forerunner for the women of the counterculture.

The ideational connection between Dodge Luhan and her bohemian friends searching for authenticity and the women of the counterculture is easy to miss. In both stories, women act as cultural producers paving a personally treacherous road to a new basis for feminism, not in male-defined equality or sameness, but in difference. The Summer of Love’s significance in the emergence of a cultural feminism that affirmed female difference has yet to be fully included in the history of both the counterculture and feminism.

29 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This was a fascinating post, and a welcome addition to the roundtable!

I was curious: how do you think this brand of feminism matches up with, say, what black women are arguing in terms of the limitations of feminist discourse in the 1960s and early 1970s? I do like this because it reminds us, once again, of how complicated the various ideologies of the Sixties really were.

Thank you Robert. Much of the feminist discourse in the 1960s was liberal and white, as you well know. They got the most attention and wrote a lot. They tended to be academics or politically active. Liberal feminists were much more concerned about political power and equality in inclusion to the current system i.e. Betty Friedan. The women that contributed to the emerging cultural feminism were more concerned with the whole structure of society that marginalized feminine values. They did not believe that political power would recognize women as women-in-their-difference. It appeared that liberals were willing to deny difference in order to gain power. Black women shared in a suspicion of liberal feminism as marginalizing black women and their particular experience of racism. Similarity here with the arguments against assimilation among Black Power leaders. Feminism, or rather feminism(s), has many streams that conflict and contradict each other. My question is how do all these different feminisms, cross-pollinating with other movements, contribute to destabilizing gender altogether as we see now? There is tons of work to be done here. Thanks.

Thanks for the response. You’re right, there’s a great deal in the historiography waiting to be written about the topics you address above! Hopefully someone reads this and is inspired. Certainly, it makes me think of the later discourse on “womanism” that would develop among some black women thinkers.

Fantastic essay! Having just finished a master’s thesis on the Haight-Ashbury I’m glad to see feminism in this discussion. Finding women’s voices in the earliest days of the Haight counterculture was often very hard. Certainly musicians and girlfriends of musicians, but never found too many roleplayers within the Haight. When I did, they were often runaways or portrayed as victim of exploitation by the male elements of the counterculture. What would you say are some of the factors that took women into these creator roles or generally more empowered roles after the Summer of Love? Would you have any thoughts on why women’s lives seemed so invisible during the early counterculture and Summer of Love?

I recall looking at so many photos of the Summer of Love with women (and POC) and wishing the photos could talk, because these voices were so often invisible in the archive.

Nice to see Lemke-Santangelo’s work mentioned here, I’m making a list of the other works mentioned, thank you for bringing them into the conversation.

Thank you and great questions. You know, many of these women are still alive. What is needed is a good oral historian to get those stories before it’s too late. Like I wrote, I have a met a few of their daughter but also some of the older women are still here. The Taos newspaper archive would be great place to look since the town was overflowing with hippies at one point causing many problems. Another source is health food store literature, and the feminist spirituality movement which produced all kinds of small papers, women’s poetry, women-only festivals, and began to flow into the New Age movement. Books like Our Bodies, Our Selves (1971) picks up many of the women’s centered sexuality issues. There is a great deal of cross-pollination between various movements were women led. As we know the counterculture was multifarious.

Hippie women leaders tended to form their own alternative spaces so you may not find them next to male leaders. They appear invisible for two reasons – male exclusion and female separatism.

The reason women took up cultural creation is because I believe they saw the lives of their mothers’ as stifling and they were also not willing to work for the “man.” This they share with men in a revolt against middle-class culture. Would like to read about what you are finding. Thanks.

Thanks for the great response! You are right about the oral history, if it had been within my budget I would have loved to have compiled one. I know Timothy Miller and the Communal Studies Society have done some oral histories with commune participants, many who began in places like the Haight. I’ve gotten a few of these transcripts and found them very useful. I’d imagine the older hippies in and around Taos may have been Haight participants as well. My research was very very focused on the Haight-Ashbury, I love the way you have folded a larger national movement into my thinking. Again, fantastic article, thank you!

The central point of being a hippie chick was to be sexually available to males. This deserves more than passing mention.The communes were nightmares in this regard. (Vivian Rothstein had an excellent piece on what she called The Magnolia Street Commune.) Battered and mistreated in this way, some might have emerged and gone on to become feminists. But rebelling against this role in various ways was pretty central to radical feminism.Hippie chicks didn’t know from Ane Koedt, Maters and Johnson, etc. To escape the complex, many made the choice of becoming lesbians

Jesse — This generalizes too much historically. Not that it isn’t true, by and large, but it’s not the only truth. Lemke-Santangelo’s book provides a wider set of empirical data and experiences. Again, to be clear I’m not writing to suggest that you are wrong, just that we should not substitute one narrative for the whole, complex history that Daughters of Aquarius reveals. — Michael

As for Tim Leary, he partook of some of the ideology that also oppressed hippie chicks. Naomi Weisstein was a student in his graduate seminar at Harvard around 1961 or 62. .He was doling out LSD to the seminar. Naomi had a bad trip. Leary and fellow students tyrannized her with the notion that there’was something wrong with her, using the same whatsamattababy line that was later imposed on hippie chicks who didn’t make themselves sexually available to males.. To her credit, she rebelled and refused..

Leary was such a conman and hustler!

I could not agree more.

cons work because both sides believe they are getting something (and bilking their printer in the process). who’s to say they’re not. personally i liked kelsey’s approach a whole lot more than leary’s

Lilian — Thanks for a fascinating read. This is the key line, I think: “In both stories, women act as cultural producers paving a personally treacherous road to a new basis for feminism, not in male-defined equality or sameness, but in difference.” To me the counterculture’s particular politics of difference **as distinguished from** the New Left’s quest for discovering the proper agent of revolutionary change (is it the proletariat? Maybe it’s African Americans? Maybe it’s the Third World? Maybe it’s women, gays, Native Americans, etc.? Maybe it’s us students ourselves?) needs more scrutiny. Sometimes the difference was grounded in essentialism: men are from Mars, women from Venus. But at other critical junctures there was something more like what Nick Bromell describes as a radical pluralism, William James-style, at work, a psychedelic embrace of the polymorphous diversity of identities and their many differences. A certain kind of feminism, mostly unexplored, under-theorized, and not entirely understood, requires more study? That’s not the New Left or Women’s Lib, exactly–that’s the counterculture when it wasn’t busy being retrograde on gender and sexuality (which was most of the time)?

Also, wonder what you think of Alice Echols’s work on Janis Joplin. I always think of her line in her collection Shaky Ground on the essay she wrote in connection with the Joplin bio, “Hope and Hype in the Haight.” Echols writes, “if the Beats were about escaping the family, hippies were about reconstituting it, in all its inequality.” That has always struck me as an intriguing argument: the interest in reconfiguring family in the Summer of Love moment away from the conventional nuclear family of the 50s; and then what that meant for women in the counterculture when it turned into the project of recovering or reconstituting patriarchy in the face of the perceived emasculation of men by that very same nuclear family/gray flannel suit society (this also puts me in mind of Barbara Ehrenreich’s work on the topic). All of which is just to say: what about the family? How does that relate to the hippie chick archetype? Just a young earth mother in training? Or other possibilities at work there, lurking in the turn to Human Be-Ins?

Michael, Thank you and I agree that “hippie chick” feminism is under-theorized. It don’t believe that they were all victims & dupes as the reader above suggested. Neither that they became lesbians out of spite. The “polymorphous diversity of identities,” evident in the counterculture I think gets us closer. This post and the reactions tells me that there is much to be done here with this group of women and what kind of feminism did they ultimately embrace. I am sure it’s all over the place and hard to categorize.

Not “spite” at all. This misunderstanding ignores the deep connection between radical feminism and the decision to construct lesbian relationships in the 60s-70s. It’s only much later that the ideology shifted to the idea that gender preference was given by nature. The latter is an idea that even many right-wingers accept now.

Vivian Rothstein, who suffered through the sexual arrangements of the Magnolia Street Commune, calls it a “New Left Peyton Place” https://www.cwluherstory.org/text-memoirs-articles/the-magnolia-street-commune

Jesse, If you have something substantial to say I suggest you write an essay and submit it to the editors of this blog. I think that would be more constructive.

like others, i have offered constructive criticism — address the substance, eg Rothstein’s commune piece.

I remember that poster. it also has baez’ mother and sister on it.

the flaw with the concept that is communicated through the poster is the gender inequity it is framed in (the draft).

the women pictured are not facing any of the pressures or choices that a man between the ages of 18 and 27 would have been subjected to in regard to saying “no” to service. there won’t be any forced vacation in Leavenworth, no leaving your home and family forever if you chose to skip out of the country. no need to pay huge legal and medical fees to beat the draft (if you had the money and connections to begin with. you haven’t got a draft card or a classification card to burn so you wouldn’t be facing federal charges for that anytime soon.

don’t get me wrong i have tremendous respect for joan baez and the work she has done for so many throughout her life. but remember it was her husband who went to prison and not her. and that this poster was not her finest hour.

i just think that a man who is sitting there thinking about all of these alternatives (with death thrown thrown in for good measure should he choose to serve – or not be able to get out of it) would not feel comforted by the poster. he might think it a cruel joke that was far from funny.

worrying about the big green hand coming down, scooping you up and then dropping you into a rice paddy or triple canopy jungle or the highlands and knowing these women were home free as far as serving in vietnam was concerned just might blind you to the poster’s attempt at humor and offer no comfort. personally i found it to be a bad joke that approaches being obscene at the time and still do.

A couple of clarifications, after Joan Baez made that poster she was visited by a group of radical feminist who set her straight– Women do not say yes to men as a reward. Women aren’t trophies. She repented of making that poster even though she was still in opposition to the war.

Michael, regarding Alice Echols, I am still exploring her work and have a contact with her. I am still researching. Can’t say much more.

Generally, there was an effort by the counterculture to reconstitute sexuality into Eros, a more politically and spiritually powerful category of human life. Sex was not just sex but able to unleash utopian energy. This is a line of research I am currently exploring which includes the theologian Paul Tillich and his definition of Eros. See “Eros Toward the World: Paul Tillich and a Theology of the Erotic” by Alexander Irwin for those interested. This view of the erotic easily disrupted traditional family patterns for new forms of kinship, everybody becomes a “brother” or “sister.” Reminds me of the free-love ethic of the Oneida community in the 19th century. See “Oneida: Free Love Utopia to the Well-set Table” by Ellen Wayland-Smith.

Also, we need to keep in mind the sex-positive feminism of the 1990s. Sex could be power women could use for their own purposes, thus “Girls say yes to boys that say no” Men don’t have all the power in sex and some feminist took that angle. Others like the radical Andrea Dowrkin saw all “penis in vagina sex” as rape. All this to say that I am not willing at this point to make broad statements about hippie chicks only that they need to be examined and not disregard as part of feminist history.

Lilian — Wow, bringing Tillich into the debates within second and third wave feminism seems very promising as a way to re-interpret this vexed history and its legacy. I am eager to follow along with where your research in this vein goes. — Michael

okay let me get this straight: “After Joan Baez made that poster she was visited by a group of radical feminist who set her straight – Women do not say yes to men as a reward. Women aren’t trophies. She repented of making that poster…”

So Baez was set “straight” by this group of radical feminists. This, to me, insinuates that there is only one way of thinking/acting and that Baez had no right to feel or think any way other than that proscribed by these feminists. She must accept. No matter that her free will was being ignored. What if she wanted to be a trophy or a reward. That was her concern and her right.

But, in “the sex-positive feminism of the 1990s. Sex could be power women could use for their own purposes,” which i take it to include being a tyranny or a reward.

Sign me confused

Andrew C. Parker — You’re forgetting just how much free love rhetoric served as way for men to demand sex from women…the patriarchal order of things was not overthrown then, and given the intense misogyny that surfaced during the last US election, I think it’s fair to say that the country (not to mention the world) still has a long way to go for true sexual liberation. I think it’s important to put criticisms of the poster in that historical context. In other words, it wasn’t—and still isn’t—just a case of free will. We are talking about deep structures of power and culture here as they manifest in a particular historical moment. Those have to be reckoned with.

That said, here’s a question that I have for everyone about the poster under dispute. Really its a reading of the poster I’ve always wanted to put forward for consideration: isn’t it using a healthy dose of humor in its antiwar effort in such a way as to also become an implicit critique of passive female sexuality?

Bear with me here a moment. To my my ears, the saying “girls say yes to boys who say no” is a bit tongue-in-cheek in that it references what was already, by 1968, an outmoded way of talking about sexual relationships. It’s like a 60s parody of a 50s saying. It doesn’t say, “Women, you must have sex with men who resist the draft or you are a fascist pig!” Of course, as with many jokes, the humor reveals power relations by trying to mask them in the funny. Still, is there not only an antiwar politics here, but a critique of a passe (and by 1968 potentially of the past) female sexual passivity.

I think this is particularly the case in part because of the gaze and body postures of the Baez sisters in Jim Marshall’s photograph. Allow me to throw the gauntlet down for a moment methodologically: here’s a case where I think social/political/and, yes, intellectual historians really have something to learn from cultural historians. In that we can benefit from investigating the source material more carefully and developing a reading of it. Instead of merely using it as flattened, one-dimensional proof of this ideology or that. What does this cultural artifact contain within it? How do we interpret its details?

So, take a closer look at the poster: https://bmgraham.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/antiwar-poster1.jpg. What stands out to me, as I began to say above, are the gazes of the Baez sisters as well as their body postures. Joan Baez takes no guff in that gaze. Her sisters neither. And look at those hats, worn askew, as well as their clothing, which bespeaks hipness, not sexual availability. Of course, their lower legs are visible, but this is very different from, say, Janis posing nude in bed with the rest of Big Brother and the Holding Company or a naked nymph goddess on a psychedelic rock poster or the groupie stereotype that would emerge in a report in Rolling Stone magazine published the following year (of course the original groupies themselves were complex figures too, as was Janis!).

But let’s stick with the photo. Whatever these three women are, they are most definitely not girls. Which is part of what makes the joke of the text above them work. Girls say yes to boys who say no, but all that’s old fashioned anyway. These are real women, and its implicitly therefore real men who would be brave enough to say no. Which of course makes for a certain kind of reiteration of age-old gender norms and stereotypes: the sexually-wise woman, the potentially de-masculinzed company man who must reassert his virility and independence by saying NO to the man. But that’s a quite different kind of sexual politics than the one the poster usually gets accused of portraying. Almost the opposite one, in fact! Now the women are actively using sexuality’s links to issues of masculinity and emasculinization as a wedge in the antiwar movement as well as the slowly emerging Women’s Lib movement (although Joan Baez always resisted being included in that movement, as she discusses in her memoir–a number of my students have done fascinating research projects on this).

Anyway, a closer reading of the image suggests, to my eyes, that these three women are not to be trifled with. The photo presents them as strong, smart, sophisticated. They are not passive, and they do not read to me as suggesting easy sexual availability in the photo.

Of course they are young and beautiful. And famous. Sure, one might read a bit of playful flirtation dancing across their faces, a willingness to engage, even perhaps a hint of need or desire. But the male gaze of the camera looks at them and what do they do in return? They look right back, with defiance.

The surroundings in the photograph double down on this message. The Baez sisters are not sprawled out on a bed. They are not posing for a Playboy spread. They sit together on a couch. They are not being touched by, or even accosted by, any men in the photograph. This is an all female setting of sisters, in a sort of bohemian apartment setting. A cool blanket covers the couch. An art print is on the wall, surrounded by two instruments, which these “girls” know how to play.

All of which is to say that if you are a man to which the text is directed, you better bring your manners, wit, style, and smarts to this photo’s fantasy if you plan to try to ask one of these women on a date, and you better have your antiwar politics figured out first and foremost.

So the poster, as a historical artifact, is—to my eye—not a simplistic text by any means. It certainly reminds us that the 1960s antiwar movement took place within the larger patriarchal and misogynistic culture of America at the time (and to this day), drawing upon and working with the dominant ideologies to try to make its stand against the Vietnam War and all that it stood for in American life, including, in a more subtle way, the conformist, restrictive gender and sex politics of the Cold War era out of which the Vietnam conflict arose.

I welcome counter-readings or interpretations of the poster, of course. I’m all ears!

Michael

So what were their draft lottery numbers? In this instance, their gender gives them a freedom not granted to men at the time. The discriminatory nature of the poster’s message was my concern.

Sign me 40

Michael, You have given us an excellent visual analysis. You just wrote an essay you could expand on. 🙂 I had hoped that image could have been used but space limited its use, I am sure. Feminism has from the nineteenth century had this internal tension about female sexuality. Thinking about Victoria Woodhull here. Is sexuality a power or is it a tool of oppression? Do women exercise sexual agency or they are repressed? What would female sexuality look like if not under patriarchal control? Liberal, radical, cultural, and pyscho-analytic, Marxist, and postmodern feminist have answered these question in different ways. Some of them are militant in their view of female sexuality. That is why everybody is confused with what “feminist” means. Andrew, the poster has to be read within the gender system of the time and working with images and attitudes that were both traditional and in flux making everybody including radical feminist uncomfortable. The hippie chick is some ways exemplify this tension about female sexuality. Excellent discussion.

The deep, macroscopic history of this, going back to the 19th century, provides a whole different way of thinking about it than the narrow focus on the postwar era. Very interesting!

I tend to look to long history. A lot of work but I think one catches things that escape us other wise. Thank you Michael and Andrew for being engaged in this conversation.

A recent example of the tension in feminism is the debate over Slut Walk. Some say it empowers women by taking back a term that has been used to shame women. Other feminist say that you can’t escape the gender system with language games and it plays right into male power.