The Ecological Imagination in Six Songs

by Anthony Chaney

In his book, The Great Derangement, Amitav Ghosh charges the modern novel as incapable of dealing with the scale of a problem like climate change. But what about songs? An argument might be made that songs have surpassed long-form fiction or even movies as the West’s primary genre, which is to say, the form in which the cultural imaginary is developed and explored.

Songs, of course, are limited. They can handle some topics better than others. If you sat down to write a song about, say, a bad love experience, you would find yourself on very comfortable terrain. Writing a song about the effects of suburban landscape on the psyche might prove to be rockier ground. Songs are often crushed under the weight of self-importance, and ecological concerns are heavy topics, to be sure. You would certainly be on safe ground using the phrase “bad love” in a song about bad love; if you were writing about your ecological consciousness, you might want to avoid that term. In 1971, Marvin Gaye famously released a song about “the ecology,” but he didn’t use the word ecology or any form of the word in the song. In fact, he barely used the term in the title, tucking it inside parentheses, and gave the song its official and more palatable title, “Mercy Mercy Me.”

Songs, of course, are limited. They can handle some topics better than others. If you sat down to write a song about, say, a bad love experience, you would find yourself on very comfortable terrain. Writing a song about the effects of suburban landscape on the psyche might prove to be rockier ground. Songs are often crushed under the weight of self-importance, and ecological concerns are heavy topics, to be sure. You would certainly be on safe ground using the phrase “bad love” in a song about bad love; if you were writing about your ecological consciousness, you might want to avoid that term. In 1971, Marvin Gaye famously released a song about “the ecology,” but he didn’t use the word ecology or any form of the word in the song. In fact, he barely used the term in the title, tucking it inside parentheses, and gave the song its official and more palatable title, “Mercy Mercy Me.”

Limits are for stretching. Given that, and given that the song is perhaps our primary and certainly most democratic genre, what are some of the other songs that have expressed and developed our ecological imagination? Here are six that came to mind, three from the period of the emergence of what historians call modern environmentalism, three of a more recent vintage.

This song from The Notorious Byrd Brothers is not The Byrds’s finest hour. It’s a throwaway tune on a good but not historically significant record. I include it here because it addresses one of the several sub-contexts from which the ecological imagination would emerges: the dolphin mystique.

Formerly mysterious, only recently held in captivity, dolphins were perceived as beautiful, graceful, playful animals whose upturned grins made them appear to be continuously happy. Familiar during this period were news reports of dolphins who sought out human beings for special friendship or for aimless frolic or who rescued someone drowning at sea. John C. Lilly published popular books and articles about teaching dolphins to communicate; meanwhile, in the popular TV program Flipper, a dolphin was a loyal and intelligent friend. Karen Pryor, a pioneer in dolphin training at Sea Life Park in Hawaii, was one of the first to appreciate the appeal of dolphins to the public and to the numerous young people who volunteered at the park as aides and trainers. Dolphins were “floating hobbits,” she said, “like aliens from space” who had descended to earth and loved us. They were as smart as we were, or maybe even smarter, since they were not at war with each other or manufactured any atomic bomb. How nice it would be to live like the dolphins! This is what “Dolphin’s Smile” asks us to do. The song celebrates dolphins as care-free, socially-evolved creatures whose smiles–tranquil, sunlit, “free from fear”–suggested a kind of non-stop high.

The less romantic chuckled. That wasn’t a smile on the dolphin’s face that was anthropomorphic projection onto the physiognomy of a foreign species. As for the media reports–what about all the instances when dolphins did not help humans in distress, when they may even have added to that distress, thus eliminating any source for a news story? Still, components of the ecological imagination are present in the dolphin mystique: the acknowledgement of a continuum between humans and other species, between culture and nature; the notion that animals are intelligent and might have something to teach us about living on the earth and with each other, something we very much need to learn.

Mitchell famously missed Woodstock but then wrote the song about it. “Big Yellow Taxi,” which precedes the song “Woodstock” on the album, Ladies of the Canyon, is about the garden, too. It’s the common declensionist narrative: once we lived in paradise, but we lapsed and paved it over. There’s an implicit shout out to Rachel Carson in the verse about DDT, but what most marks this song, in terms of the emerging ecological imagination, is the sanguinity of its mood. The singer is fun-loving, playful, a little goofy. The songs ends with a laugh. Yes, human beings have a tendency to destroy the good that they have, but if the listener is tempted to feel bad about that, the song’s third verse undercuts the temptation. The taxi in question is the one that took the singer’s “old man” away. Presumably, Graham Nash had to go play a gig with his new singing group, and darn it, if she doesn’t miss him, too.

It wasn’t as if Mitchell was afraid of taking on serious topics—far from it. She wasn’t afraid to preach. “We’ve got to get back to the garden,” she sings in “Woodstock,” but neither in that song nor in “Big Yellow Taxi” is there the notion that we aren’t capable of regaining paradise in some form or another, or in any case, doing better than we’re doing now. Both “Dolphin’s Smile” and “Big Yellow Taxi” are lacking in the agony over environmental destruction that would mark many songs to come. Neither evoke the prospect of apocalypse; neither are the least bit resigned to some eventual collapse into dystopia. Whether they learn from dolphins, travelers along the road, or just good common sense, human beings are redeemable.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that two songs from this list, “Big Yellow Taxi” and “Out in the Country,” were released in 1970, a seminal year in the history of American environmentalism. The first Earth Day was celebrated that year. It’s the year Nixon signed the bill that created the EPA. But again, given the times, the 5-month gap between the two releases is noteworthy. Every month marks a further deterioration in the hope associated with Sixties-era activism, every month an increase in disillusionment. “The dream is over,” John Lennon sang in a song released in December of 1970. He was singing in reference to a band he used to play in, but he might as well have been speaking of the era in general.

So note the difference in mood between “Out in the Country” and “Big Yellow Taxi.” The former is mournful, elegiac, a mood gorgeously stated in the keyboard figure that introduces the song. Paul Williams was one of the great pop songwriters of his time, and he captures the cultural moment with precision. The city is deteriorating; it’s polluted, full of smog; overcrowded, politically fraught. When the state of the city gets to be too much of a downer, the singer heads out to the country for some peace. Note, too, that a degree of resignation has set in. The singer is going to the country “before the breathing air is gone, before the sun is just a bright spot in the night time.” There’s no question but that the air will become unbreathable and the sun will be blotted out by the smog or perhaps some nuclear winter. Some form of nature therapy has been a part of American thinking at least since the transcendentalists. But this near-hopeless resignation, this retreat to private solutions, mark a particular turn in the times. We once thought we might figure out a way to be like the dolphins. That seems like forever ago.

A few years later, the film Soylent Green would depict the city when there is no country left to retreat to. Rather, when life becomes unlivable, you can purchase a comfortable suicide. You’ll get a comfortable seat in an auditorium and be shown, during your last few moments, beautiful images of a nature that’s gone. The character played by Edward G. Robinson (in his last film) buys one such suicide, and his eyes fill with tears, remembering the way the world used to be. He might have been a small child back in 1970 when the Three Dog Night song came out. Now its chorus has proved true. The breathing air is gone, and the sun has just about disappeared behind a carbon blanket that retains the sun’s heat but renders it nigh invisible.

A lot of time has passed since “Out in the Country” and Soylent Green. Resignation to environmental collapse has reached a degree of density and mannerism in the works of expressive culture. Dystopian visions have been detailed and refined. The Mad Max films (1979, 1981, 1985) have provided an enduring iconography: people living in the desert, the failure of infrastructure made visible. Nothing new is being made; nothing is being replaced; all innovation is innovation of scavenging, maintenance, and repair. In short, it’s a patched-together world of souped-up hard terrain vehicles and make-do weaponry. Generations have arisen who have no memory of the world before the collapse. Some of them have formed a band called Gorillaz. (Gorillaz is a virtual band consisting of animated figures who appear in videos online.) They are cute and cool purveyors of post-apocalyptic chic, with pug noses and bad teeth. Their eyes glow with the chemicals they’ve ingested, deliberately or otherwise. They make music together when they aren’t battling some enemy tribe. They’re damn good!

This is a step beyond resignation. Not knowing the old world, these kids don’t mourn it. Unaware of the old myths, they live the new ones. David Byrne hinted at the new skills necessary in “Life During Wartime.” Gorillaz have perfected these skills and then some. The singer in Byrne’s song didn’t have any records to play, but Gorillaz found some records and instruments in the ruins; they jerry-rigged some amps and a record player. This is the world we live in, the song says. It’s a world where the survivors are the ones who never falter in their vigilance. Because no one never falters, “we don’t have a chance.” It’s not a world where dancing makes sense anymore, and yet the singer can’t help it: “All I do is dance.” The younger sand urchins love it. They look on and learn. Resignation here is not privatist, as in “Out in the Country,” but social. The implication is: we are tough and flexible. We will find a way to survive.

This is the title song from an underrated record about the politics of climate change. The song admits to a sobering truth: we don’t have to imagine Mad Max scenarios anymore. Those scenarios are coming true. They are coming true in the experience of weather events once deemed unprecedented and abnormal. They are occurring mostly and most regularly in a broad swath around the planet corresponding, more or less, to the equator. In this swath are clustered nations of the “undeveloped” world. The people of color who live in these nations have been suffering the consequences of empire for generations. The latest of these consequences now comes in the form of climate change. These people are the ones both least responsible for the carbon particles in the atmosphere and most victimized by their effects. Scholars and researchers call this the global south. If we were to look for something equivalent to this dynamic in the continental United States, we would immediately point to New Orleans and Katrina, which is the setting for Costello’s and Toussaint’s record.

An environmental historian recently described to me the basic situation as he perceives it. First, there is a way of thinking that favors modernization, control, growth, and development. This thinking represents all the components of industrial capitalism from its beginnings to the present day, an economic order based on the profligate exploitation of resources, both organic and non-organic, both human and non-human. Second, there is an alternative way of thinking that has been around just as long. This way counsels humility, austerity, and economic restraint. This way advocates for egalitarian social arrangements and respects the living world in all its forms. In an American context, this way follows Thoreau, George Perkins Marsh, Alice Hamilton, John Muir, Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold, and more. The problem is that this way of thinking is a tiny, weak rivulet in the cultural imaginary, and the other way of thinking is a pounding, gushing river. When Costello asks, “What do we have to do to send the river in reverse?,” this is the river he means.

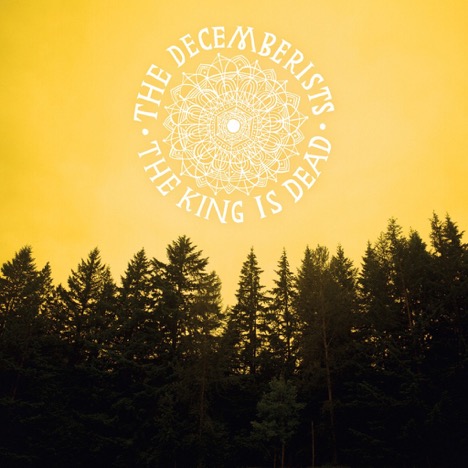

This is the opening song on the Decembrists’ biggest album, The King is Dead. Most of the chatter about this record was about the band streamlining their sound, about songwriter Colin Meloy turning his attention away from English folk music and turning instead to American roots. There was a lot of talk about how this record sounded like REM, about how it was as if Peter Buck had become, for this record, a virtual member of the band. I saw the whole record as one about the ecological imagination, and where it is today.

Much came together to give me this impression. The band is from Portland, Oregon, first of all. It was recorded it out in the country, and the cover features a line of evergreens, typical of the Pacific Northwest. Behind this line of trees, the sky is yellow, suggesting a fundamentally altered climate. The record’s title and the band’s name appear in the middle of this sky in the shape of a dominating sun. Nature imagery dominates the songs; several of them seem to be exploring a near-future, after the existing economic orders have collapsed. The king is dead. The river has not reversed, but it has dried up completely, in both a literal and a metaphorical way. Big-hearted former Portlanders—real people, not animated–are finding new ways to live. Their politics have become radically decentralized, with all the tedium and challenge that brings. While certainly no paradise, it is a way of life in which people are less alienated, one might say, from the material world that sustains them.

Much came together to give me this impression. The band is from Portland, Oregon, first of all. It was recorded it out in the country, and the cover features a line of evergreens, typical of the Pacific Northwest. Behind this line of trees, the sky is yellow, suggesting a fundamentally altered climate. The record’s title and the band’s name appear in the middle of this sky in the shape of a dominating sun. Nature imagery dominates the songs; several of them seem to be exploring a near-future, after the existing economic orders have collapsed. The king is dead. The river has not reversed, but it has dried up completely, in both a literal and a metaphorical way. Big-hearted former Portlanders—real people, not animated–are finding new ways to live. Their politics have become radically decentralized, with all the tedium and challenge that brings. While certainly no paradise, it is a way of life in which people are less alienated, one might say, from the material world that sustains them.

Did I take my interpretation a bit far? Maybe–but not too far! Good songs are ones that can bear a plurality (but not an infinity) of interpretations. Listen to “Calamity Song,” “Down by the Water,” “This is Why We Fight.” Listen to the opening song, which to my mind, lays out this basic theme. Changes are occurring now, and bigger changes are coming. It feels overwhelming; it’s a lot to bear of present-day environmentalist ethos. Yes, we are, each of us, responsible (and certainly Americans a lot more than others). At the same time, we are not–not any one of us–in control. Even if we could act collectively, that collective wouldn’t be in control. That reality is a lot to bear. But when the agony of ecological consciousness gets too heavy, don’t escape it in the direction of denial or resignation. Rather, carry it, keep carrying it, but don’t carry it all. The desperate desire to do some world saving can be a species of hubris all its own. Therefore, the message of the song gives one, if not hope, heart. I take from this song the same slim but substantial comfort that I take from Arne Naess’s reminder that, when it comes to environmental activism, “the front is long.” You can’t do everything. Do what you can.

________

is a Lecturer in History and English at the University of North Texas at Dallas. He received a PhD in Humanities/History of Ideas from the University of Texas at Dallas in 2013. His forthcoming book, Runaway: Gregory Bateson, the Double Bind, and the Rise of Ecological Consciousness, is now available for preorder.

12 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

When I think environmentalism and music, this is the first contemporary song that comes to mind–ANOHNI’s 4 Degrees.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NJBPKKH2P1g

Thanks, Roger, for introducing me to this song. Hard-hitting.

The first song that came to mind for me is from Randy Newman’s Sail Away album, “Burn On” (1972): http://www.pophistorydig.com/topics/cuyahoga-river-fires/

Wow, yes. “The Lord can’t make you burn.”

Thanks Patrick.

Love the middle eight.

Anthony, I hope at some point you will blog about your book on Bateson. Your title alerted me to the fact that I have nothing by or about him in my bibliography for Ecological & Environmental Politics, Philosophies, and Worldviews (available on my Academia page)! And one more thing, it was a pleasant surprise to see a reference to Arne Naess, about whom I’ve heard very nice things from my former teachers, Nandini (now a dear friend) and (the late) Raghavan Iyer. Raghavan wrote an incisive and sophisticated comment on Naess’s formal systematization of ‘Gandhian Norms’ at the Institute of Philosophy and History of Ideas, University of Oslo, in 1958, which is reprinted in an appendix to the 1983, 2nd edition, of Iyer’s book, The Moral and Political Thought of Mahatma Gandhi [OUP, 1973]). I don’t know details about their friendship, but I’ve heard several stories about him and he seems to have left a rather deep and warm impression on them.

Patrick, yes, I do plan to blog about my Bateson book. I appreciate your interest. In the meantime, I’ll download the bibliography you’ve compiled … and add, I’m sure, to my reading list.

Out at sea for a year

Floating free from all fear

Every day blowin’ spray,

In a dolphin’s smile

Wind-taut line split the sky,

Curlin’ crest rollin’ by

Floating free aimlessly,

In a dolphin’s smile

Rainbow’s end everywhere,

Full of light, free as air

Childhood’s dream,

Have you ever seen a dolphin’s smile

I’m sorry, but I can’t see where David Crosby’s “Dolphin’s Smile” is concerned in any larger way with the environment or environmental movement or even dolphins as a political tool. (Though it was released several years later, his and Graham Nash’s “Critical Mass/To the Last Whale” better serves that purpose, I think. Or for a singer/songwriter who was more personally involved with dolphins there would be Fred Neil.

Instead, I see the song dealing with the narrator’s feelings as he sails the ocean over a long period of time and experiences the timeless freedom nature affords him. It is the same freedom that the dolphins he sees gliding near his boat every day enjoy He feels akin to the creatures and imagines himself sharing much with them in his present condition.

He has no agenda, no schedule, or no destination other than following this feeling. And if he is experiencing a “non-stop high,” it is a poetic/emotional high rather than a political/rational one. This experience is also important in psychedelic culture and its embrace of drugs. LSD could make you see the world anew just like a child and bring about a renewal of childhood, according to Beatles chronicler John Savage.

Or as playwright Arthur Miller observed: “And so the sixties people would stop time, money time, production time and its concomitant futurism. Dope stops time. More accurately, money time and production time and social time. In the head is created a more or less amiable society with one member, a religion with a single believer. And the pulsing of your heart is the clock and the future is measured by prospective trips or new interior discoveries yet to come. Ken Kesey saw America saved by LSD once: the chemical exploding the future forever and opening the mind and heart to the now, to the precious life being traded away for a handful of dust.

This alternative reading of the lyrics also presages Crosby’s own adventures at sea that grew from his ownership of Mayan, a schooner he bought in 1967 after he was thrown out of the Byrds. Crosby borrowed $25,000 from The Monkees’ Peter Tork and traveled to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in search of a schooner. After buying Mayan and learning how to sail her, Crosby sailed to San Francisco and began living on her full time in 1970. He owned the boat for 45 years and sailed the seven seas during that time.

As an aside, I would disagree that the Notorious Byrd Brothers is “not [a] historically significant record.” The album was lauded on it release by such esteemed critics as Robert Christgau, Sandy Pearlman, Jon Landau, David Fricke, and Parke Puterbaugh. Reviews aside it’s my opinion that the album is superior to Sgt. Peppers Its americanness makes it so. I am attracted to the sense of open space that the album conveys. In this it is truly American, something which shows up in the sound and subject matter of many of the songs. It glides and ascends and reaches for the heavens. It is what Hendrix called “western sky music.”

Thanks.

Andrew, thank you for filling in these interesting details surrounding “Dolphin’s Smile.” Out on his boat, Crosby was living like the dolphins—at one with nature, so to speak. That seeking for atonement is an important aspect of the ecological imagination. A distinction should be made between the ecological imagination as I discussed it and any politics associated with modern environmentalism. I think it’s safe to say, however, that those fascinated by dolphins as creatures living happy, free, and fearless would likely have been favorable to an environmentalist politics a few years later, David Crosby included.

I like the way you describe the sound of the Notorious Byrd Brothers album. I personally prefer the albums that preceded it and the one that came right after, but it’s a good one, no doubt, highly praised then and now.

I agree with this point about connections between imagination and politics.

Yes, it is indeed important to carefully analyze how these do, or do not, overlap. (For instance, in what ways did John Denver actually support environmental activism and research?) Writing a song is not really promoting sustainability.

But I think it is worth highlighting the significance of interest in dolphins. That is such an atypical topic for popular culture. Particularly since, unlike Flipper, this song doesn’t present the dolphin within the more familiar framework of a pet. It is worth discussing those artworks that reflected upon the world beyond humans, and on how that imaginative work is part of environmentalist thought.

Points well taken, but my perspective is more on the metaphorical side of things.

The first five albums are the Byrds to my mind. Great stuff with the exception of Mind Gardens. Sweetheart is separate, I think, but superior in what it was, which was an inspiration for such as Dillard and Clark, New Riders, Poco, the Dillards, the Burritos, etc. Have a good one.

Thanks for the post! This is a topic I have spent a fair amount of time reflecting on; glad to see other analysis. Not much work has been done on this… perhaps in part because popular music is so light on references to the environment that go beyond the surface.

(I will plug my article on this topic, “‘I’ve Seen It Raining Fire in the Sky’: John Denver’s Popular Songs and Environmentalist Memory,” in Dragoslav Momcilovic, ed., Resounding Pasts: Essays on Literature, Popular Music, and Cultural Memory.)

I appreciate the attention to two common tropes in popular culture related to environmental issues: survival in dystopian future, and rural escapism.

Nice job drawing connections on dolphins. Holy cow, they were actually referred to as ‘little hobbits?’

I think you might overestimate the difficulty in using keywords about environmental issues. But I do believe that it has proven difficult for most songwriters (John Denver one of the exceptions) to develop an extended reflection on an experience of, or interaction with, the environment.

I find it strange how American popular music typically implies that humans and what they have built is all, or almost all, that exists in the world. Many poems have been written on experiences of nature – why not popular songs? Are there significant traditions of songs about the environment in past centuries?