James J. Kilpatrick has been on my mind lately — partly because he figures in Nancy MacLean’s excellent history of economist James M. Buchanan’s role in the long-game political project of Charles Koch and his fellow travelers on the radical right, and partly because he figures in my own education, an early influence in my long apprenticeship as a writer.

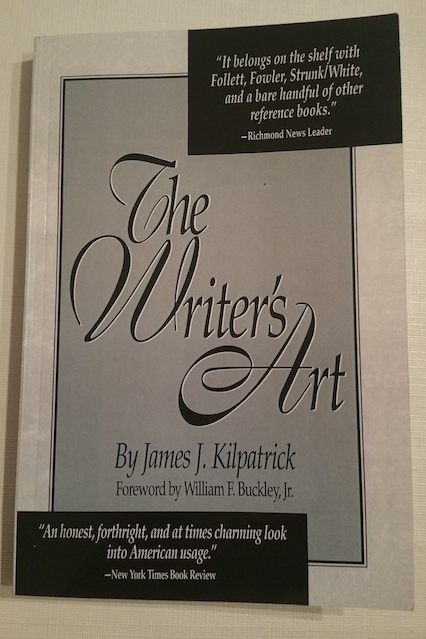

When I was in junior high and high school, our local newspaper carried Kilpatrick’s syndicated column, “The Writer’s Art.” I read this with great interest – it was one of the first places where I encountered the idea of writing as a craft, a skilled practice requiring the mastery of tools and techniques. That was a very different conception of writers and writing than I had absorbed or experienced to that point: the Romantic notion of writing as a matter of inspiration, as the spontaneous outpouring of some inner impulse to creative expression through words on the page. That was what I knew of writing, and that was how I approached it – or how it approached me.

Kilpatrick’s workmanlike vision did not eclipse my earlier conceptions of what a writer does and is. Alas, I still believed in the Muses and their gifts. Sometimes I still do. But thanks to Kilpatrick and some other influences – Zinsser’s On Writing Well, a much more salutary guide, in my view, than the tedious Strunk & White

; John Irving’s novel The Hotel New Hampshire (it’s a long story — I’ll explain later/elsewhere); my brusque, demanding, slyly empowering sophomore English teacher — I came to recognize that, even if such gifts were necessary, they were not sufficient.

So what were some of the practical lessons I took away from Kilpatrick’s syndicated column on writing?

The usual stuff: attention to word choice, avoidance of awkward constructions, properly sequencing items in a series for maximum rhetorical impact. Cadence. That’s a big one: silent words on a page have a rhythm, a sound. Write for the ear, not for the eye.

These insights were not unique to Kilpatrick, even then. And that last one especially – sound has a sense, sense has a sound – was, I think, already an instinct for me. But Kilpatrick spelled these truisms out, a few hundred words at a time, on the regular, in a forum that reached all the way to the flat, fertile farmlands of the San Joaquin Valley. And these were some of the lessons I took from Kilpatrick.

But Kilpatrick’s column conveyed more than simply his sense of a writer’s craft. Kilpatrick’s column reflected his ideas, his values, his political commitments, his economic views. Sometimes he was very straightforward in arguing for a particular policy stance. In a column that ran on April 8, 1984 in the Pensacola News-Journal and elsewhere, Kilpatrick railed against a 1982 U.S. District Court decision requiring the state of Washington to equalize pay for women and men employed by the State in the same job grade and classification.

Kilpatrick rhetorically conceded that a court-ordered solution to the problem of unequal pay would be a great idea, if the problem were so simply solved. But, he wrote, “[t]his is the problem: The apparent inequities could not be thus resolved without wholesale abandonment of the principles of a free marketplace. The idea is superficially plausible. It is fundamentally implausible. It could not work in either public or private employment unless both labor and management were to abdicate their functions. That Orwellian day may come. It is not here yet.”

I’m not sure that column had anything at all to do with the craft of writing, beyond running in Kilpatrick’s usual slot. Anybody who opened the paper that day looking for tips on how to write a smooth transition or what makes for a good metaphor might have been a little disappointed. I don’t recall whether I read that particular column or not. If it did run in our paper, then I probably looked at it.

I would have been far more likely to read one of Kilpatrick’s frequent jeremiads about the corruption of the English language, the faddish coinage of new words, and – significantly, given the cultural conflicts of the time that have since become the focus of my research – the sad decline of higher education (“Maybe John can’t write because his teacher can’t,” Jan. 2, 1982, [Binghamton] Press and Sun-Bulletin) or the pernicious effects of sex-inclusive language (“Obsession with sexism weaves linguistic briers,” Feb. 20, 1982, [Binghamton] Press and Sun-Bulletin). In that column, Kilpatrick bemoaned the use of the term “freshpersons” in a Montclair State College orientation manual:

Freshpersons? The strained formation offers one more melancholy example of the offenses that often are committed in an effort to avoid offenses. One imagines the plight of the poor dean: on one side the importunities of the egalitarians, on the other the sensibilities of those who love the mother tongue. The dean succumbed to the egalitarian demands, and out came ‘Freshpersons.’

The “plain meaning” of Kilpatrick’s language here, to use a term being bandied about in discussions of MacLean’s book, is clear enough: the term “freshpersons” and similar gender-neutral coinages constitute infelicitous innovations that degrade rather than strengthen the English language. But there’s much more in this brief passage, never mind the whole column, than a simple defense of current English usage. There is, first of all, the implicit devaluation of “egalitarianism.” In Kilpatrick’s formulation, one can either be “egalitarian,” or one can “love the mother tongue” – one cannot hold both positions at once. Moreover, Kilpatrick implies, love for the mother tongue is simply a sensibility; it makes no “demands,” it importunes no one. All the demands – such an uncivil practice, to make demands! – are coming from the “egalitarians.” Egalitarianism is a force for cultural decay.

To be sure, Kilpatrick deploys a “to be sure” – or at least its rhetorical equivalent – in order to anticipate the counterarguments of those who would point out that language and usage are not fixed forever but change over time.

I do know that our language changes, melds, yields to customs and to changing mores. It seems to me that those of us who write for a living have an obligation – up to a point – to accommodate the many persons who are genuinely offended by what they perceive as the sexism of our language…But there comes a point at which this deference becomes ridiculous.

The rest of Kilpatrick’s column consists of an elaboration of that idea — feminist demands have become ridiculous – and includes a rousing defense of “the essential genderless neutrality of ‘man.’”

Yes, these are judgments about language and usage; but they are also at the same time judgments about current politics, current cultural conflicts, crises (real or imagined) in higher education, the deleterious influences of “a vociferous minority of militant feminists,” among whom there is apparently no one who truly loves “the mother tongue.” Those ideas were certainly not the primary focus of Kilpatrick’s oeuvre throughout the full syndication of his column, “The Writer’s Craft.” But they were part of what he communicated through that column, little doses of right-wing politics (and plenty of sexism, which doesn’t seem to have a fixed political valence) embedded in paeans to good prose style. A young apprentice writer reading Kilpatrick’s column would certainly absorb those lessons too – would, and did.

Live and learn. I sure have.

12 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Great piece. For more on Kilpatrick’s reactionary politics (intriguingly tangled up as they were with his views on writerly craft), there’s a very helpful biography out there: https://www.uncpress.org/book/9781469602134/james-j-kilpatrick/

i have always been of the opinion that while one can learn to write one cannot be taught to write.

I tell my students this, and that to become a good writer you have to write…and to read good writing.

Thanks for this LD. I’d like to second the person above who linked to the James J. Kilpatrick biography; I was about to do the same!

I have to say, growing up I knew Kilpatrick for his columns in our local paper about writing style as well. When I first read about his defenses of segregation–and, later, his integral role in the rise of the New Right–it took me a while to realize it was the same writer as the person who produced those newspaper columns. His mastery of words made him a dangerous political opponent; knowledge is power, after all, and being able to shape how others obtain that knowledge (through the written word) makes one quite powerful.

Robert, I had exactly the same experience. I was in grad school, and kept reading about James Kilpatrick the staunch segregationist newspaperman, and I did not connect him, at all, to the writing advice columnist. I didn’t figure it out ’til I read Kilpatrick’s obituary. (Yes, I can be slow on the uptake.) And then I was like, “Whaaaa?”

And you are absolutely right about words, language, rhetoric and power. That’s why we gotta pay attention to the full register of meaning, and sometimes play the soft parts loud so people can more clearly make out the message being conveyed on the sly.

I disagree with the idea that writing is something that cannot be taught. Writing can be taught just like any other practice that’s a mix of knack and skill. Some people will be a quick study, some people won’t, some will improve a little, some a lot, and — like learning to play the piano — there’s no improvement without practice. But there are good teachers who help you work through your mistakes, and I had four good English teachers in a row in high school (though, to be fair, I suppose I was a pretty good English student).

Certainly, there’s something a little mysterious and psychically fraught for any of us about our own writing (at least there is for me). So if this comment sounds like me whistling past the graveyard, I suppose that’s partly right. A friend told me just the other day, “The words come more easily to you.” That’s a post over at my own blog, but for here I’d just repeat what Anne Lamott says in Bird by Bird: if you have those kinds days (and sometimes I do), you pay through the nose for them. Ain’t nothin’ easy about manning the floodgates — not when the words come in a torrent, and not when the channel is dry. I pay for every word just the same as anybody else.

In any case, there are other books and sources I’d recommend to someone looking for writing advice besides Kilpatrick. I picked up and carried forward a lot of ideas from him that I could have done without — or so I imagine. But, given where I’d come from and where I was and when I was, it might be that staunchly believing in “the essential genderless neutrality of ‘man,'” at least for a time, was what allowed me to ever write anything at all.

I always appreciate reading your reflections, LD, and this one is a gem. A resonant gem, to mess up my metaphors mightily!

The most a teacher may be able to do is teach you is something about the writer’s tools – grammar, spelling, style (in the sense of appearance of language), etc. What he or she can’t do, however, is bring these things together for a student in ways that communicate how to actually write. Sure, the tools or building blocks are important, but they are not the thing itself. That can only come from within you.

I think this quote from Eugene Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery explains it pretty well:

“In the case of archery the hitter and the hit are no longer two opposing objects but are one reality. The archer ceases to be conscious of himself as the one who is engaged in hitting the bulls-eye which confronts him. This is a state of unconsciousness realized only when completely empty and rid of the self, he becomes one with the perfecting of his technical skills, though there is in it something of a quite different order which cannot be attained by any progressive study of the art.”

I never took a writing class, per se, in 17 years of schooling (though, I did do a lot of writing in my other classes and read a ton of books for school and on my own), Nor did ever read a book on writing. Despite this, I managed to put together a long and successful writing career, and I still have no idea how I learned to write.

I guess we’ll just have to agree to disagree.

I have an entire chapter about him the *Richmond’s Priests and Prophets* (okay, it’s really two). He saw himself in the style of H. L. Mencken. If you take a step back (a looooong step back) from his racial screeds and harsh conservatism, he wrote well and gave remarkable writing advice. I have argued that he was the intellectual architect of massive resistance. One of his wittier moments, however, occurred in a private letter about the student sit-ins that occurred in Richmond. He noted the white ruffians harassing the bespectacled black students reading Plato (or Aristotle) would suggest that he had picked the wrong side.

As for my writing instruction, Zinsser’s *On Writing* was the most helpful to me and Anne Lamott freed me in *Bird by Bird* of harsh criticism of my writing [we all have it but we need to listen to it less].

Doug, thanks for this fantastic comment, and especially for the anecdote from his correspondence. His aside there is pertinent, I think, to my own work on the fault-lines of campus controversies in the 1980s. You didn’t share a link to your book, so I will: Richmond’s Priests and Prophets: Race, Religion, and Social Change in the Civil Rights Era

And I am always glad to meet another academic who has found Bird by Bird helpful. I re-read it about every six months or so, just to get my head on straight. Such a humane and generous book. And yes, alas, to the harsh self-criticism. My mental dial is tuned to Radio KFKD way too often.

I didn’t come across Lamott until about 2004 or 2005 I think, but she has been good company ever since. I’d also highly recommend Stephen King’s On Writing — another humane book, but one that takes a very workmanlike, demystifying approach to the subject. Also funny, but in different ways.

Anyway, thanks for the further insight into Kilpatrick. “The intellectual architect of massive resistance” — very nicely put.

Thanks. I’m still learning about the art of self-promotion. I left out the link to the book. Dealing with Kilpatrick made me a more humane historian. I found much of his constitutional arguments insulting and his personal racism painful. But wrestle I had to because Kilpatrick was building a framework that sounded too familiar to me in the late 1990s.

Thanks for King suggestion. I’ve seen it but not picked it up. As for Lamott, her description of a shifty first draft was so compelling I finally realized why I stunted my own writing. I tell undergrads every semester everyone writes shitty first drafts but recognizing the good pieces is what makes us better writers. That and giving the work over to trusted readers.

Yes, I sometimes assigned her chapter “Shitty First Drafts” to my rhet/comp sections. The next chapter, “Perfectionism,” is also good for students (and their profs!). The chapter on “Jealousy” is good too — probably more for profs than for students. Lamott is one of those writers who has been able to strike that elusive balance between moral seriousness and not taking oneself too seriously. Very good company.