Continuing our roundtable exploring the bicentennial legacy of the Era of Good Feelings, today’s post is by Emily Conroy-Krutz, assistant professor of history at Michigan State University and the author of Christian Imperialism: Converting the World in the Early American Republic (Cornell, 2015). You can find out more about her work at her website, emilyconroykrutz.com.

At a Congregational Church in Bennington, Vermont, things were not going well for Rev. Edward Hooker. His Missionary Monthly Concert sermons were disappointing. No matter how hard he worked, the congregation did not seem to grasp his central message.

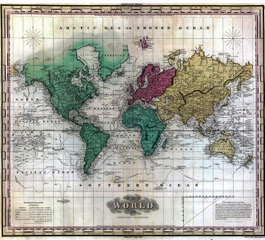

He decided to try something new. A large wooden board, painted white, with a ring at the top, by which it could be suspended. A jar of India Ink, into which he dipped a feather to trace out the bold, strong lines of continents and national borders. The completed map was raised up above the pulpit, ready for him to point to with a staff, showing his congregation the places to which he was referring, giving them food for the eyes and not just for the ears. A map, the pastor hoped, would make all the difference.

Success! “That dark and gloomy map,” he reported, “did the work which I had not been able to accomplish with my most pains-taking and earnest preaching. It accomplished the direct and solemn impression, that indeed ‘the world lieth in wickedness.’”[1] Shaded according to the supposed “civilization” status of any given spot, Hooker’s map draws our attention to the connection between the missionary movement and broader American conversations about the world in the early 19th century. Hooker was not the only missionary enthusiast pulling out the India Ink, after all: ministers and lay supporters alike were excited to use maps and other tools to educate audiences about the world. We only know of Hooker’s efforts, after all, because he wrote them down to share his tips and tricks with others facing similarly unenthusiastic audiences.

Throughout its history, an important part of the foreign missions movement was communicating what they termed “missionary intelligence,” sharing information about the world with their domestic supporters who might never leave their home communities. By the 1830s, missionary promoters were convinced that it was only American ignorance about the world that prevented the mission movement from receiving the high levels of support that they felt it deserved. The solution to such a quandary was for the foreign mission movement to continue to educate the country about the world at large. Geographic, ethnographic, and political information about the world made up much of the published materials of the mission movement of this era.

This educational role reveals the ways that missionaries saw themselves as important mediators between the world and the nation. Like trade and commercial networks of the same era, the foreign mission movement connected the United States to a much larger world. If we want to understand the mental map of early 19th century Americans, the foreign missions movement provides us with a helpful point of entry. And if we want to understand the diplomacy of the early republic, we ought to think more about these missionaries.

By the 1840s, American missionaries could be found in South and East Asia, in the islands of the Pacific, in the Middle East and the Mediterranean, in West and South Africa, and of course in North America. They decided where to go based on careful deliberations over a given area’s status as “civilized” or not. The “heathen world,” as they called it, had many potential mission stations. In order to make the most productive choices, missionaries used a sort of ranking system that I have called the “hierarchy of heathenism” to help them structure their choices.[2] From its very beginnings, the mission movement asked Americans to consider, for example, whether Louisiana or Ceylon was a better site for American missions. To missionaries, the answer was rather obvious: Ceylon.[3]

For those Americans at home who might never travel the world, these missionaries provided a window to the world at large. They were, after all, prolific by necessity: it was their writing about the world that generated the fundraising that could support their work overseas. Because missionaries were long-term residents, they claimed a special authority and expertise about the places and peoples among whom they lived. And because their evangelization paired Christianity and “civilization” as a matter of course in this era, their commentary was not confined to theological topics.

The “missionary intelligence” of this era accordingly became an important part of what Americans knew, or thought they knew, about the world. It found its way into geography textbooks and other venues, bringing missionary frameworks and priorities beyond the audiences who actively sought it out.

As we think about the role of missions in shaping Americans’ mental map of the world, we might imagine ourselves in the pews, watching Rev. Hooker jab at the points on his map. The globe was a “vast field” in a missionary fight to “set up the standard of redeeming love, here and there,” he tells us, taking the time at certain points to delve into greater details.[4]

Missionaries were an important part of their country’s engagement with the world in these years; they became a sort of unofficial, and often troublesome, branch of American diplomacy as they brought Americans into the world and the world back to America.

[1] Edward Hooker, quoted in American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, On the Use of Missionary Maps at the Monthly Concert, (Boston: Crocker and Brewster, 1842), 9-12

[2] Emily Conroy-Krutz, Christian Imperialism: Converting the World in the Early American Republic

(Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015), ch. 1

[3] Gordon Hall and Samuel Newell, The Conversion of the World or the Claims of Six Hundred Million and the Ability and Duty of the Churches Respecting Them, 2nd Ed. (Andover: The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, 1818), 32-33.

[4] Hooker, quoted in The Use of Maps, 20.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This post made me curious about a print culture question: what of map ephemera—pamphlets and leaflets that were used to promote the cause, presumably by circuit riding missionary promoters? Has anyone done a study of this kind of ephemera in 1810s-1820s churches?

Also, did Monroe’s Era of Good Feelings promote this feeling of a need for “missionary intelligence”? – TL