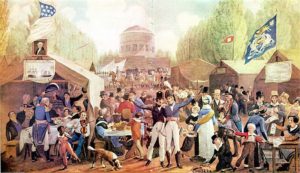

“Independence Day Celebration in Centre Square,” John Lewis Krimmel, 1819

This week, we’re hosting a special roundtable highlighting the bicentennial legacy of the Era of Good Feelings (1817-1825), a key period that has shaped how we frame American foreign relations. First up: a look at the state of the field and what’s new to say about the era. Today’s post is by Dr. Thomas Balcerski, assistant professor of history at Eastern Connecticut State University. His book manuscript, “Siamese Twins: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King,” explores the concept of personal and political friendship in nineteenth-century America.

The year 2017 marks the beginning of the bicentennial of the “Era of Good Feelings.” That by-gone era, officially begun with the inauguration of President James Monroe in 1817, completely collapsed with the inauguration of President Andrew Jackson twelve years later. Along the way, few good feelings were felt; the old two-party system of Federalists and Democratic-Republicans collapsed into a raucous one-party mass; and weighty issues surfaced pertaining to economic development, to territorial expansion, and, yes, to American foreign policy with foreign nations.[i]

Certainly, the Monroe Doctrine has emerged as the most significant diplomatic by-product of the Era of Good Feelings. The eponymous doctrine, which actually rejected a diplomatic rapprochement with Great Britain over the future occupation of Caribbean territories and argued for two spheres of influence, one for the United States (in the Americas) and another for Great Britain (in the rest of the world), has nonetheless spawned generations of intellectual thought about American foreign policy. Studies of the Era of Good Feelings and the Monroe Doctrine, ranging from the political to the imaginary, have stressed precisely this point: the Monroe administration claimed much and imagined more in its imperialistic declaration.[ii]

Typically, historians have taken the foreign policy of the Era of Good Feelings as a jumping off point for other aspects of later American diplomacy. Fewer still have integrated the political history of the era with those same issues. Matters changed somewhat over May 26-27, 2017, when the Lebanon Valley College Center for Political History hosted its first annual conference on the topic of the “Era of Good Feelings.” At one panel, titled “An Era of Good Feelings: Really?”, several panelists questioned the very notion of such an amicable moment in American history, while another addressed the inner workings of the Monroe administration. Generally speaking, the conference attendees left with much to ponder and compare to the events of two hundreds years ago, though the ultimate lesson may be this: in 2017, discontents as we are, quiet we cannot let any era of good feelings lay.

Among the nine sessions on the conference program, however, none dealt directly with American foreign policy in the age of Monroe. While a conference dedicated to political history might not have attracted papers related to foreign policy issues, the lack of even a single essay on the seminal Monroe Doctrine seems more than an accidental lacuna. At the heart of this absence lay a greater problem within American historiography: the history of American foreign policy has been traditionally separated from the political history of the United States. For generations of foreign policy scholars, the value of the Monroe Doctrine lay primarily as a historical antecedent to the later actions of the more imperial administrations of William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, while for political historians, the doctrine stands as an secondary sidebar to the wider workings of the early republic.[iii]

So, might there be a way to situate more effectively these two historiographies? Interestingly, Daniel Walker Howe, who provided the conference keynote address, may have provided a way. Howe considered the relation of John Quincy Adams to slavery and argued, with an assist from the work of Matt Mason and David Waldstreicher, that slavery privately troubled JQA, but that the son of a Federalist president publicly practiced a politics of pragmatism respecting the peculiar institution. Slavery, of course, has been at the heart of longitudinal studies of American history for generations. Recent books by Stephen Chambers and Matthew Karp have stressed just this point, situating the history of enslavement at the heart of American foreign policy in the first half of the nineteenth century. Perhaps it should not surprise that scholarly attention on such issues as the transatlantic and domestic slave trades should supersede studies of diplomatic relations with Europe.[iv]

Herein lay a key insight to the dusty historiography of American foreign policy during the Era of Good Feelings. Its continued relevance lay primarily in how the era set the stage for the conflicts over slavery in the succeeding ages, from the presidencies of Andrew Jackson to those of the later imperialists through the present day. The continued integration of histories of American slavery with those of American foreign policy presage an era of new (and possibly even good) historical feeling on these two favorite scholarly concerns.

[i] On the Era of Good Feelings, see variously George Dangerfield, The Era of Good Feelings (New York: Harcourt, Brace, & World, 1952); the essays in Robert V. Remini and Edwin A. Miles, eds., The Era of Good Feelings and the Age of Jackson, 1816-1841 (Arlington Heights, Ill.: AMH Pub. Corp., 1979); and most recently, Michael J. McManus, “President James Monroe’s Domestic Policies, 1817-1825: ‘To Advance the Best Interests of Our Union,’” Companion to James Madison and James Monroe, ed. Stuart Leibiger (Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 438-55.

[ii] For an historiographic overview of Monroe’s foreign policy, see Sandra Moats, “President James Monroe and Foreign Affairs, 1817-1825,” Companion to James Madison and James Monroe, ed. Leibiger, 456-71. On the Monroe Doctrine, see Jay Sexton, The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2011); and Gretchen Murphy, Hemispheric Imaginings: The Monroe Doctrine and Narratives of U.S. Empire (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2005). For older, but still useful studies, see also Ernest R. May, The Making of the Monroe Doctrine (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1975; the one-volume Dexter Perkins, A History of the Monroe Doctrine (New York: Little, Brown, 1955); Albert Bushnell Hart, The Monroe Doctrine: An Interpretation (Boston: Little, Brown, & Co., 1920); and George F. Tucker, The Monroe Doctrine: A Concise History of its Origin and Growth (Boston: George B. Reed, 1885). And on the continued legacy of the doctrine, see also David W. Dent, ed., The Legacy of the Monroe Doctrine: A Reference Guide to U.S. Involvement in Latin America and the Caribbean (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1999).

[iii] See, for example, Walter LaFeber, The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860-1898 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1963).

[iv] Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009); and David Waldstreicher and Matthew Mason, ed., John Quincy Adams and the Politics of Slavery: Selections from the Diary (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016). Stephen Chambers, No God But Gain: The Untold Story of Cuban Slavery, the Monroe Doctrine, and the Making of the United States (New York: Verso, 2015); and Matthew Karp, This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2016). See also John M. Belohlavek, “John Quincy Adams, Diplomacy, and American Empire,” in A Companion to John Adams and John Quincy Adams, ed. David Waldstreicher (Malden, Mass: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 281-304; Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government’s Relations to Slavery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), esp. 89-134; and Belohlavek, “Let the Eagle Soar”: The Foreign Policy of Andrew Jackson (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1985).

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Since JQA was one of the first, if not the first, American of note, and the first of Monroe’s cabinet, to broach the acquisition of Cuba (the famous “ripe fruit”), his anti-slavery stance was faint indeed at this time.

Is it not true that foreign policy lay West, in the sense of conquering the inland empire—of taking control of the Louisiana Purchase, for example? – TL