During the past week, I had the opportunity to spend five (very) full days with ten fellow scholars doing research in the Hoover Library and Archives, as part of that institution’s Workshop on Political Economy, organized by Jennifer Burns.

George Nash has written a fine study of Herbert Hoover’s relationship to Stanford University, with a detailed history of the beginnings of the archival collection that would form the core and in some ways the crown of the library’s holdings. (Here is a brief account of how the collection got its start.)

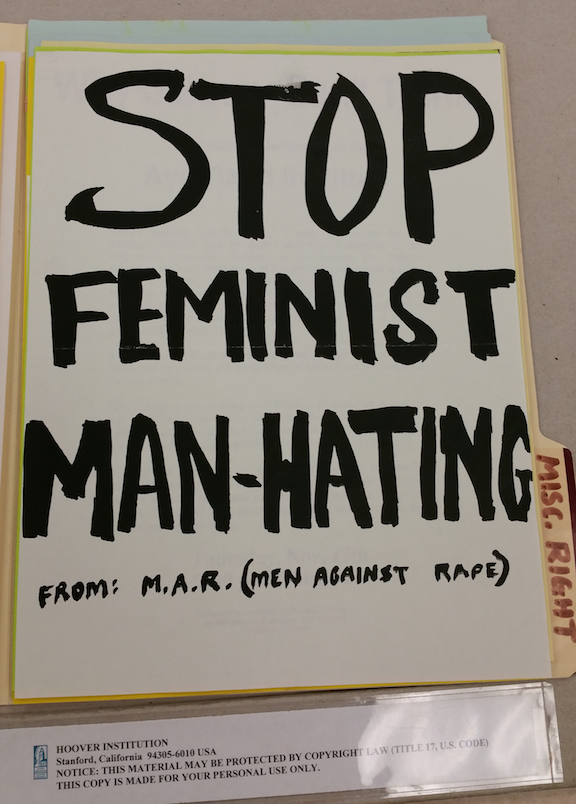

Herbert Hoover gave a crucial directive to those he commissioned to gather documents (on the downlow and on the government’s dime) in the wake of the Great War and the Bolshevik Revolution: whatever else they found, they should be sure to gather “fugitive materials.” By this he meant things like posters, pamphlets, handbills, placards, underground press publications, newspapers, tabloids, programs, notices, broadsides – all the ephemera of political movements and historical moments, the texts and images that were printed to serve an immediate purpose and not designed or expected to endure beyond their contemporary use.

It was a prescient proviso, paving the way for a massive collection of materials on “war, revolution and peace” in the 20th century, a collection that is unparalleled anywhere in the world.

I spent a fair amount of time this week looking at some fugitive materials from the last quarter of the 20th century. I was working with a lot of different archives, including the massive holdings from the American Council on Education, the papers of John H. Bunzel

, and – my absolute favorite – the Sidney Hook collection. (I will have lots more to say about the inimitable Sidney Hook.)

But one of the most amazing collections I consulted was very small – just a single archival box with a dozen or so folders. This was the Tim Davenport collection. For a couple of years in the late 1980s, Tim Davenport went around the campus of the University of Washington, Seattle, and collected a copy of every handbill or flyer that he came across, advertising everything from anti-apartheid rallies to Unification Church meetings. He organized them into folders by organization / cause, and the collection included a couple of folders filled with conservative / rightwing documents.

I’ve posted a couple of pictures from the collection in this post. Taken in its entirety, the Tim Davenport collection offers a unique window into the intersection of politics and campus life at UWash Seattle in the late 1980s.

To my great frustration, I have not been able to find a comparable archival collection for Stanford University in the late 1980s. There probably is such a collection – at least, I hope there is – but it most likely consists of a folder or two in some professor’s or administrator’s personal papers. Looking for such a folder in the dizzyingly vast collections of the Stanford Libraries or the Hoover Archives is orders of magnitude more challenging than finding the proverbial needle in a haystack. It will be sheer serendipity if I ever find it.

Serendipity…or someone doing me a solid.

If you have any leads on collections of fugitive materials from Stanford in the 1980s, please let me know. It’s for a good cause — the cause of history.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Some pics of the campus here, including a couple from the top of HooTow.