Two recent essays have caught my eye in recent days, forcing me to think even harder about the importance of history to modern political and cultural debates. Both illustrate to me the reason why recent history is such a crucial aspect of the historical profession. While it is often easy to use comparisons to the nineteen-sixties when talking about the chaos of modern politics—and we should all brace ourselves for next year, which will mark numerous fifty-year anniversaries for the calamitous events of 1968 (you were warned)—or the “malaise” of the nineteen-seventies, it is time to also think about historicizing the nineteen-nineties. Events in that decade say as much about our current predicaments as much as referencing the Cold War, the Civil Rights/Black Power era, or the “Age of Reagan” of the eighties.

Andy Seal’s essay from several days ago

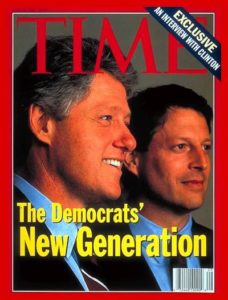

, offering new frameworks through which to think about the end of the New Deal era, was one such piece that got me thinking more about the nineties. His arguments about how the archives point to interpretations of the shift away from the burgeoning New Deal welfare state to a more neoliberal, austere government apparatus in the United States is one that will continue to spark debate on our site for weeks to come. As it should. Seal’s argument that some political and intellectual historians are beginning to think more about the Democratic Party’s own weaknesses that hurt and, ultimately, led to the rollback of some (but, as both he and Tim Lacy in the comments for that piece make sure to state, certainly not all) New Deal-era reforms is one that is important to the history of the nineties. As Seal noted, President Clinton’s embrace of a more moderate course—influenced, of course, by the earlier ascension of the New Right within the GOP and their capture of the White House through Reagan in 1980—mirrored the problems liberal Democrats had in holding on to their political power within the Democratic Party.

hurt and, ultimately, led to the rollback of some (but, as both he and Tim Lacy in the comments for that piece make sure to state, certainly not all) New Deal-era reforms is one that is important to the history of the nineties. As Seal noted, President Clinton’s embrace of a more moderate course—influenced, of course, by the earlier ascension of the New Right within the GOP and their capture of the White House through Reagan in 1980—mirrored the problems liberal Democrats had in holding on to their political power within the Democratic Party.

At the same time, it would be foolish of us to leave out the foreign policy of the nineties as well. Tensions between Russia and the United States are at an odd crossroads. Democrats increasingly distrust Vladimir Putin, a marked contrast to John Kerry mocking Mitt Romney’s hawkish foreign policy towards Russia in 2012 as being reminiscent of Rocky IV. Much of the foreign policy and intelligence establishment has been angered by Russia’s assertive foreign policy maneuvering in recent years, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and their intervention in Syria showing Putin’s willingness to flex military and diplomatic muscle. Above all, however, continuing revelations about the scope of Russian influence on the American election has put Moscow back in American headlines in a way that could easily remind one of the worst days of the Cold War.

But looking back to the Cold War would only partly explain how we got here. Putin’s belief the collapse of the Soviet Union was a disaster for the world is relevant to present  worries about US-Russian relations. But remembering that Russia had a difficult nineties, while the United States entered an era of prosperity matched by a “hyperpower” status around the world, helps us to think about how we got to this moment of national doubt. American intervention in Bosnia and Kosovo, the expansion of NATO, Russia’s quagmire in Chechnya, and collapsing post-Soviet economy all provide some important context for current tensions.

worries about US-Russian relations. But remembering that Russia had a difficult nineties, while the United States entered an era of prosperity matched by a “hyperpower” status around the world, helps us to think about how we got to this moment of national doubt. American intervention in Bosnia and Kosovo, the expansion of NATO, Russia’s quagmire in Chechnya, and collapsing post-Soviet economy all provide some important context for current tensions.

I also believe Ibram X. Kendi’s new essay in the New York Times also bears reading and thinking about in context of the 1990s. His basic thesis, that black death is virtually central to America, is haunting and sobering to think about. It also fits when one thinks about the nineties in historical context. The Los Angeles Riots of 1992, and the Rodney King beating that proceeded it, provide a reminder that the crises in Ferguson,  Baltimore, Minneapolis, and elsewhere are nothing new (just as, of course, Watts in 1965 or Miami in 1980 told activists that the problems of the L.A. Riots of 1992 weren’t new). That this year is the twenty-fifth anniversary of those riots offers as good a time as any to think about how the problems of police brutality that sparked that riot still plague us today. The festering problem of racism in eighties and nineties intellectual discourse provide considerable intellectual fodder for both Andrew Hartman’s War for the Soul of America and Daniel T. Rodgers’ The Age of Fracture.

Baltimore, Minneapolis, and elsewhere are nothing new (just as, of course, Watts in 1965 or Miami in 1980 told activists that the problems of the L.A. Riots of 1992 weren’t new). That this year is the twenty-fifth anniversary of those riots offers as good a time as any to think about how the problems of police brutality that sparked that riot still plague us today. The festering problem of racism in eighties and nineties intellectual discourse provide considerable intellectual fodder for both Andrew Hartman’s War for the Soul of America and Daniel T. Rodgers’ The Age of Fracture.

Debates over affirmative action, the Bell Curve, the War on Drugs, and welfare reform weren’t so long ago. In fact, these debates still rage on today, albeit in different forms. I cannot, for instance, think about the mid-nineties argument over the Bell Curve’s thesis of innate differences in intelligence based around racial categories without considering clashes between some on the “alt-right” and a resurgent Left around ideas about race, free space, and racial and cultural diversity. Some of the figures in these debates, not surprisingly, remember 1994 quite well—and have become embroiled in today’s debates.

I wish to emphasize that by no means should we discard further study of the sixties, seventies, or eighties—or for that matter, earlier periods. But it is increasingly clear to me that understanding how we came to have such a polarized nation, confronting a world that appears to be headed toward a multi-polar order, means grappling with a period in American history that is just starting to garner attention—and truly seems, in some aspects, to be another country. And as I read over my essay, looking (and likely failing to see) typographical errors, I can only ruefully chuckle at the story of my childhood–filled with concerns about the problem of racism in American life, the vexing question of Russia, and a Clinton at the center of a moderate-liberal split in the Democratic Party.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Excellent article, Robert. I’m writing this note because I see that you are studying history at the University of South Carolina and that you’re interest in post-1945 Southern history. I’m Glenn Jordan (in Cardiff, Wales), the younger brother of Professor Grace Jordan McFadden, an oral historian and expert on the Civil Rights Movement, who taught history at USA in the 1970s, 80s and 90s; she was also director of African American Studies. I assume you’ve seen her Her 25-part videotaped series, “The Quest for Human Rights: Oral History of Black South Carolinians”? Best wishes.

Ah yes, I’m familiar with her work! She’s still remembered fondly here, and I know of the series you’re talking about (I’ve used some of it for research). Glad to make your online acquaintance!

Here’s an earlier post on the 1990s that contains a number of great insights and suggestions from readers–including yourself, Robert!

https://s-usih.org/2016/02/the-1990s-in-historical-perspective.html