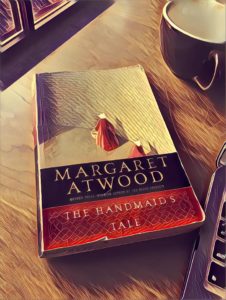

When I heard about the new TV series based on The Handmaid’s Tale, I decided to do something I don’t usually and actually read the book first. (Fancy that!) As so many have relayed over the years, the effort was well worth it, and as a book that explicitly revolves around questions of sex, gender, and power, it is a gold mine for historical reflections and speculations.

Beyond this general relevance to historians, the book is actually capped by a section that tackles questions of the historian’s task directly. In “Historical Notes,” we peek into a lecture, given by a professor at a symposium for scholars of Gilead, the society from which the handmaiden’s tale hailed. The lecture is set 200 years in the future and yet, feels very familiar for those acquainted with academic settings. There is the boring introduction made by the event’s organizer, sprinkled with at least a few jokes to keep it merciful; the boomerang flattery that, by design, ends up reflecting well on the speaker; and the ostentatious display of technical knowledge coupled with the parenthetical phrases that speak to a socially validated belief in one’s undisputed intellectual prowess. Without the venue being described, my imagination easily filled in the details that matched the tone – a beautiful, likely medieval-inspired lecture hall, filled with white men of all ages in button down suits, laughing and clapping politely. Even if all the professors presenting at this seminar are not white and male (and there are hints that they are not) the atmosphere communicates a heavy sense of whiteness.

The keynote speaker is giving a talk on the book itself, which emerged as a set of cassette tapes in a metal footlocker. There’s much recognizable here to the historian, from the problem of dealing with an old medium (they had to reconstruct a machine to play the tapes) to the challenge of identifying the author, and probably more to unpack than I’m capable of, seeing as fiction is not really my thing. One passage though doesn’t require a sharp literary eye to appreciate. “If I may be permitted an editorial aside,” the professor begins, “allow me to say that in my opinion we must be cautious about passing moral judgment upon the Gileadeans. Surely we have learned by now that such judgments are of necessity culture-specific. Also, Gileadean society was under a good deal of pressure, demographic and otherwise, and was subject to factors from which we ourselves are happily more free. Our job is not to censure but to understand.” (Applause.)[1]

After reading 300 pages detailing the horrors of a racist, antifeminist society from the viewpoint of one its oppressed members, this cavalier commentary feels, proportional to the ease with which it is delivered, incredibly heavy. I’ve no intent to imagine that I know what Atwood was intending to suggest when she wrote this passage, or even that I understand how “intent” factors into fiction writing exactly, anyway. But my feeling was one of sinking familiarity: because isn’t this so often how we talk, we historians? Isn’t this how we sound in the conference rooms of four-star hotels and the halls of Ivy League universities? We must, of course, understand – and we must contextualize in order to understand, and together the knowledge thus gained is more useful, intellectually and ethically, than condemnation. But is censure incompatible with understanding and, even more disturbingly, are the uses to which we put such historicism always good ones? What does it mean, for example, if a white male historian of the twentieth century implores others – many of which are not white men – to understand the slaveholding of Thomas Jefferson or James Madison “in context”?

If the purpose is to remind ourselves that “there but for the grace of God go I,” this is a worthy goal indeed – but, that doesn’t always seem to be the point. On the contrary, when it comes to discussing the ethics of the founding of the United States, in particular, we are often told to be attentive to how progressive the young republic was – once again, we’re reminded, considering the context! Some historians, such as Gordon Wood, even argue that because white men experienced the revolution as a leveling event, we should consider it radical, even though for so many others, it was a life sentence of slavery or a death sentence of genocide. One of the characters in The Handmaid’s Tale who enjoys one of the top positions of power actually makes this exact point, when asked how he could think the new society they created improved on the one they destroyed. “Better never means better for everyone,” he replies. “It always means worse, for some.”[2] What caught my eye here is that although this is spoken from the vantage point of a powerful man in a patriarchal, anti-feminist society (so, easy for him to say), his character never denies the nature of what he helped create – he owns it, and states as necessary the suffering of others to make the improvement for all “better.” But we cannot at all say the same for those still inclined to think on the revolution as radical, whether they be a professional historian or just someone with a passing interest in politics who likes to quote Jefferson. They do not claim to view as a positive good nor a necessary evil white supremacy, imperialism, and the oppression of all who challenge gender norms. And yet despite their stated opposition to such evils, they direct our attention elsewhere; to the “radical” stuff.

Rather than to further ask why this happens, I want to ask what happens when we so shift our gaze. In particular, what happens to the cherished task of, to put it casually, keeping things in context? When we teach our students more about the life of Thomas Jefferson than the lives of the slaves he owned, the stuff about him we do identify with becomes the real stuff of history: the ever forward moving “progress,” of, say, egalitarianism among white men. Meanwhile, the ugly stuff falls into the background as exactly that, behind the main scene, simply there as necessary to the foreground but not really an essential part of it. That stuff is really part of the past, which our poor founding fathers, being human and fallible, were naturally still bound to in some respect. All the good things they said and did, however, that’s

the future – that is History. So now we’ve reified something without even realizing it; somehow, an oath to contextualization is often sworn right before it is betrayed by the construction of scholarly narratives.

Something else weird also happens along the way. Some might still make a fuss, asking how such brilliant and idealistic men fell for such lies as white supremacy or Manifest Destiny – they figured out monarchy was a dumb idea after all, right? But reasons for this are quickly provided and, again, context saves the day! What else could we realistically ask of them, all the way back in the eighteenth century? They were, after all, men of their time, even as they created the ideas necessary to usher in the future. We can’t ask more of them, we can’t judge them from our vantage point, from what we now know – that’s not really being fair, is it?

But to make this move in turn involves a strange kind of condescension, painting the elites of the past as somehow incapable of taking in critiques of the practices of power in their times. They might have been smart, in other words, but they weren’t gods or saints. Once again, in the “Historical Notes,” section of The Handmaid’s Tale, this attitude pops up briefly when the professor is discussing the identity and social position of the anonymous author before the dystopian takeover. “She appears to have been an educated woman,” he says, “insofar as a graduate of any North American college of the time may be said to have been educated. (Laughter, some groans.)”[3] So, is that the excuse that will be provided for us, 200 years hence? That we just weren’t really equipped with the knowledge to understand what we were doing when we created mass incarceration or placed property rights over human rights?

But of course, we know this isn’t true. What we lack isn’t knowledge, and ignorance cannot explain away, say, the Trump Presidency, just for starters. And here’s the kicker – it is not true for the past either. We know the oppressed have always fought their oppression and that, one way or another, their dissent was registered in the minds and nightmares of those with power. Moreover, we also know that the ideologies that justify power usually come after such power is established, not before. For example, the most ardent, fully developed theories of white supremacy followed after the establishment of slavery, not before – they developed as justifications, precisely because white masters knew there was something calling out for justification.[4] They were not ignorant, no more in any fundamental sense than we are. And yet, sometimes we’re told their ways of thinking and knowing were so drastically different from ours, that to condemn the bloody institutions they built is to read the present back into the past. My reply – after this long and winding ramble of a post – is that it is this assertion, in fact, which is more ahistorical than any censure or condemnation of such men and women ever could be.

[1] Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale (New York: Anchor Books, 1998), 302.

[2] Atwood, Handmaid’s Tale, 211.

[3] Atwood, Handmaid’s Tale, 305.

[4] I owe Ibram X. Kendi for reminding me of this key insight, as I was recently listening to the introduction of his excellent book, Stamped From the Beginning.

9 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

You know I am one of your biggest fans, and again this is a great piece. Well said. “But my feeling was one of sinking familiarity: because isn’t this so often how we talk, we historians? Isn’t this how we sound in the conference rooms of four-star hotels and the halls of Ivy League universities? We must, of course, understand – and we must contextualize in order to understand, and together the knowledge thus gained is more useful, intellectually and ethically, than condemnation. But is censure incompatible with understanding and, even more disturbingly, are the uses to which we put such historicism always good ones? What does it mean, for example, if a white male historian of the twentieth century implores others – many of which are not white men – to understand the slaveholding of Thomas Jefferson or James Madison ‘in context’?”

Without moralizing about the past, I think you have made an interesting connection to Atwood here. I think you are onto something really important here. The ideology of oppression typically follows the real world enactment of that oppression, or one could say, the dominant cultural producers of a given society are given more and more incentive to normalize and justify those systems of oppression.

I think this is why it is so important for historians to dedicate themselves to the project of a usable past, not just to be contrarian but to assist in the construction of counter hegemonic movements.

Again, well said. Really enjoyed it.

I think there are some distinctions to be made about the presence of moral judgments in history (i.e. historical texts). Three come to mind immediately. First, those judgments must be earned by the hard work of the historian in exploring the nooks and crannies of the topic at hand. So we have earned v. unearned judgments (#1 distinction). Next regards frequency (#2). One doesn’t want to be accused of over-moralizing a topic. When you see that, you question whether the historian has fully explored and understood the varying levels of context of varying episodes in the text. The last (#3) concerns whether the judgment matters to today’s readers—i.e. does it touch on something that is still important? Does that judgment seem consequential relation to subsequent scholarship and historical events? …That’s it for now. But I think this comment goes to your own “sinking familiarity” observation per the last chapter of the book. – TL

Robin,

It’s been many years since I read The Handmaid’s Tale and my recollection of the book is rather hazy — I’d entirely forgotten the ‘Historian’s Notes’ at the end.

I read down to this in your post —

Even not remembering the novel well, I think it’s pretty clear that the intent here is satirical. Atwood is taking a particular scholarly cliché — ‘one must understand rather than judge’ — and applying it to a context in which the reader, having just read about the society in question, appreciates that it’s rather ludicrous to say this. Hence, satire. That at any rate is my somewhat off-the-cuff take, but I think I probably would come to the same conclusion if I were to re-read the book.

It may be relevant to note that Atwood isn’t a stranger to the academy and thus was/is very able to contribute to the mode of academic satire if she wanted to.

Along the lines of your comment about not being a stranger to the academy, it might be well worth noting that she, Stephen King, Ben Bova, and many more I’m missing all dabbled at one time or another as professors. What then does it say about academic culture that some of the authors most talented at turning society down dark corridors are those trained to research and teach?

Have read the rest of the post now.

I think both condemnation and praise (hagiography, whatever) can be somewhat dull. Which is not to say they should or can always be avoided.

The other point I’d make is that words, once written down and/or published, can take on a life of their own that goes beyond what the author specifically meant by them — I’m thinking here of Jefferson’s words in the Decl. of Independence that everyone knows, “we hold these truths to be self-evident [etc.]” — I don’t even have to write it out.

What these words meant to Jefferson is not quite what they mean to us (e.g., our definition of “men” in “all men are created equal” is much more expansive — we read “men” as “humans,” not white males), but the words are at a high enough level of generality that they transcend the author. That is presumably one of the premises of Danielle Allen’s book on the Decl. of Independence (which I haven’t read but I recall a Crooked Timber symposium on it).

Yes, Jefferson was a slaveholder and a racist and (in some sense) imperialist (the “empire of liberty”). I just don’t think reading 300 pages of condemnation of Jefferson would be that interesting.

As long as that condemnation was connected to a historical and political critique (i.e., not just ranting), I think it would be rather interesting. So do some others as well, I guess, since it has basically been done:

https://www.amazon.com/Master-Mountain-Thomas-Jefferson-Slaves/dp/0374534020

Thanks for the link.

I was thinking about doing a write up on this section myself. Interestingly, in the Kindle version of the book, the Historical Notes section is “missing-ish.” They’ve programmed the book to route you to the Amazon site as soon as you finish the major story line, completely eliminating the Historical Notes component. You have to go back to the book to read the final section, which is a bit disappointing as I think it adds quite a twist on the rest of the Tale.

It absolutely does!, that is so ridiculous they do that.