What follows is a guest post from one of our very thoughtful undergraduate students at Belmont, Jordan Heykoop. Jordan has just graduated with a degree in history. He wrote this paper as part of the requirements for an upper level course in transatlantic intellectual history I offered this past spring called “International Vistas: the U.S. Viewed from Abroad.” For this particular assignment, I asked the students to write about either Godard’s Breathless or Henry James’ short story “The Jolly Corner.” The idea was not for them to write a formal research paper, but rather, write a think-piece given the conceptual “toolkit” we put together through the semester, using different thinkers’ ideas about “America” and the like. This is what he came up with, and I wanted to share it with our readers. Enjoy. Jordan is happy to respond to any comments or suggestions.

Americans are lonely. “Americanization”–understood by European intellectuals and political leaders in the twentieth century as an export of American products and values, an investment strategy to control the economies of other countries, an attempt to educate foreigners in the superiority of American institutions, or a process of modernization, all in the name of the free market–was in some sense an export of glorified loneliness.

A democratic and capitalist spirit cultivated this loneliness in America. Alexis de Tocqueville observed that aristocracy made “of all citizens a long chain that went up from the peasant to the king. Democracy, on the other hand, “breaks the chain and sets each link apart” as it constantly draws each individual “back towards himself alone and threatens finally to confine him wholly to the solitude of his own heart.” People in a democratic era are no longer bound through loyalty and obligation, values which are far-reaching and stable, but through common interest, which is malleable and subjective. Individuals gather to negotiate and calculate their interests, then disband. This sense of equality breaks social and communal links and leaves the individual looking inward for identity, place, and meaning.[1]

For Max Weber, a Protestant society, free from the structure and liturgy of the Catholic Church, cultivated a deep inner loneliness in which individuals worked desperately to discern signs of God’s favor. This discipline and sense of calling in a worldly vocation created the foundation for a capitalist spirit–the conditions under which a free market economy could thrive. America is the paragon of these processes. Late capitalism had become a “monstrous cosmos,” a world where the values of hard work and the sense of inner loneliness remained entrenched, but were completely unhinged from any religious foundation or teleological connection.[2] This American brand of loneliness was commodified, advertised and exported across the Atlantic in the mid-twentieth century. Jean-Luc Godard’s film Breathless is an exploration of and response to the consequences of imported American loneliness.

American mass culture throughout Western Europe after World War II was striking in its pervasiveness. Movies, rock and roll, jazz, newspapers, magazines, advertising, and television captured the “collective imagination” of European audiences. These sounds and images were created for the common folk, and American mass culture was so dominant it did not feel like an import to European consumers; its conventions were imbedded in the consciousness and experiences of its audiences.[3]

American journalism in particular captivated European audiences. American news stories were aimed at audiences with a short attention span, who wanted to be amused as well as informed. American reporting developed a formula of objective reporting mixed with eye-catching graphics, punditry, and gossip. American films also captured the European imagination. Movies seemed less verbal, languid and abstract than European films. They were cinematic, driven by narrative, action and spectacle. American films engaged and entertained audiences rather than attempting to instruct and enlighten–in other words, bore–them with high-minded philosophies and values.[4]

Jean-Luc Godard was among a group of young intellectuals in France who crafted favorable and extensive reassessments of American films in the 1950s. These critics evaluated American movies on philosophical and aesthetic levels, impressing otherwise ordinary films with rich meaning and metaphors. In raising movies to the realm of art, they hoped to become artists themselves. Godard wrote for the influential journal Cahiers du Cinema. The Cahiers writers praised the directors of American films–customarily considered hired hands–as auteurs

. Artists struggling against the ignorance of mass audiences, the unimaginative visions of producers, and a demand for commercial entertainment, the auteur became a master of subtlety, style, and indirection. He was the real creator of the film. The director controlled lighting, angles, and pace, which he used to infuse the film with meaning–the mise-en-scene.[5]

In this setting of pervasive “Americanization” and French criticism of American film, Jean-Luc Godard’s film Breathless was a response to American mass culture. As both writer and director, Godard was the true auteur. He created a work of art that could entertain an audience and appreciate the innovation of American directors while critiquing the imported ideals of American society.

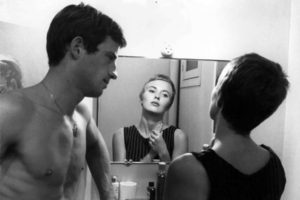

Breathless tells the story of Michel, a petty car thief turned wanted criminal, and his American girlfriend Patricia, an aspiring journalist who sells the New York Tribune in Paris. Michel impulsively kills a police officer after stealing a car, and must acquire a loan from a friend in Paris to flee to Rome. Michel tries to convince Patricia to run away to Italy with him. In the end, Patricia calls the police on Michel, and he is shot in the back and killed. Breathless is the story of two characters who play-act American ideals of independence, and are unable to connect and escape their isolation.

In style, Godard creates a personal and intimate film. He employs long continuous shots that achieve verisimilitude–the story is believable. Shots of Parisian monuments, buildings, and streets are striking, and establish a context in which, like the importation of American mass culture, ideas of America play out in a French setting. The camera is often focused on the individual–the character’s facial expressions and internal deliberations are on display. At the same time, Godard’s noticeable use of jump shots create a fast-paced narrative. The film takes on the pace and thrill of the police’s chase. At times, the characters turn and talk to the camera. The director’s presence is known, and he invites audience to join in.

Godard’s principal characters, Michel and Patricia, reveal how impoverished ideals of independence lead to an isolating loneliness. Michel aspires to be American, and his play-acting becomes his demise. Michel longs to be an American gangster–cool but not conspicuous, witty but not garrulous. Michel’s idea of America is clearly and curiously shaped by American cinema.

Michel smokes incessantly. He peruses newspapers for pornography. He dresses like a mobster. He wants to sleep with American women, drive American cars, and watch American movies. Outside a movie theater, Michel walks in front of a poster for Humphrey Bogart’s last film The Harder They Fall. “Bogey,” he mumbles. Michel’s remark takes on a double meaning.

He suggests “bogus,” a disbelief that his crime spree must come to an end. “Bogey” also invokes “Bogart”–it comes across as a familial and endearing nickname–the last name of the American actor whose likeness he attempts to imitate. Michel sees no distinction between actor and character. He wants to be Humphrey Bogart in speech, dress, and manner, because that would mean being American. He even walks around throwing punches at the air like the boxers in the film, suggesting his efforts at imitation are futile if not comical. Michel is a walking caricature of the American penchant for violence, glorified crime, and independence.

For Michel, independence entails acting outside of sexual and legal boundaries without consequence. He tries endlessly to convince women to sleep with him. When Patricia tells him she is likely pregnant with his child, though, he blames her: she should have been more careful.

He steals cars but shows no fear of being caught. After killing a police officer and seeking refuge in Paris, he sees his face in the newspaper each day but maintains an air of nonchalance.

At the end of the film, Michel accepts his demise. When the police arrive to arrest him, Michel does not hide. He refuses a getaway car and a gun. He knows from any American gangster film that the higher and faster he rises, the harder he must fall. Michel romanticizes the criminal’s fate, and his actions reveal an American faith that law and justice will prevail. Michel knows he can only run from the law for so long, and his capture is the pre-ordained denouement of the captivating drama. Or perhaps, Michel is truly oblivious to his impending fate, and he represents an American innocence and naïveté toward context and larger processes.

Patricia, an American journalist living in Paris, strives to become happy while maintaining her independence. Her attempts feel frustrated, and she is unsure why. In a meeting with an editor of the newspaper, she remarks, “I don’t know if I’m not happy because I’m not free, or if I’m not free because I’m not happy.” Patricia recognizes she is unfree, but confuses positive freedom with negative liberty in her pursuit of happiness. Freedom, understood by Hannah Arendt, consists in having access to the public realm. Individuals in a public space, who discuss, deliberate, and debate ways in which to constitute themselves with their share of public power, are experiencing freedom. To America’s founding generation, this share of public power, the right to be a participator of public affairs, brought a sense of happiness they could acquire nowhere else. Freedom is positive–a power to act, to commune, that creates public happiness. Liberty is essentially negative. Liberty is protection from oppression and obligation by the government in the pursuit of private interests.

Patricia is unhappy because she is unfree. She maintains an impoverished view of freedom that can never bring happiness, as she insists on her desire to be independent. When she enters her apartment to find Michel waiting on her bed, she remarks under her breath, “I can’t ever be alone when I want to.” Patricia wants to be sexually and financially independent. She turns down Michel’s sexual advances time and time again, though eventually always acquiesces. When he asks her, “why bother writing?” she replies, “to make money and not rely on men.” In a word, she wants to left alone. Beyond transgressing gender expectations, Patricia’s insistence on self-reliance points to an American disillusionment with independence–she is free by her own definition but feels unfree. She should be happy by her own standards but knows she is not. A journalist, she would rather interview others and report stories than be known herself. Patricia hopes to be outside the realm of public affairs, to sell the news but not be a part of it.

Patricia’s penchant for independence, and the unhappiness she cannot make sense of, expresses American society’s lost legacy of their Revolution: the positive freedom created in the republic is confused with negative liberty, and the public happiness enjoyed by the founding generation is lost to private happiness. Perhaps to be American is to feel unhappy and unfree, and not know why. In this sense, mass entertainment is also a diversion, an escape from existential ennui and discontent it helps create. The theater becomes a cultural temple, a momentary respite from spiritual loneliness.

“Let’s go see a Western.” Michel suggests to Patricia as the inspector follows their trail. The Western was a manifestation of the American imagination. Its exportation to and acceptance by European audiences informed their notions of American values and ways of life.

The hero of a Western was violent, rugged, and independent. He traveled and worked alone, acting outside the law to impose a higher sense of justice. He smoked, wore a hat well, and seduced beautiful women–the kind of man after whom Michel models himself. Instead of going to see the film, Michel and Patricia act out as outlaws in a Western, fleeing from the police in a stolen American car. There is no divide between art and life, as the two characters embody caricatures of tragic lovers caught up in a crime spree. The two run from the authorities together, but their lives remain separated.

Rilke’s observation that “modern life increasingly separates men and women” surfaces in Patricia’s interview with author Parvulesco. He is understandably unwilling to argue with the great poet, but seems unconvinced by this proclamation. When asked about love in modern society, Parvulesco ends up confusing eroticism and love, and contends they are the same. Eroticism is libidinal and selfish; the subject seeks to gratify sexual desires. Love is mutual, giving, and holistic; subject and object—the lover and beloved—are held in common commitments, and their interplaying desires cannot be compartmentalized. In turn, Parvulesco unknowingly concedes Rilke’s point: modern life conflates eroticism with love, selfish gratification with sacrificial commitment, and consequently separates and isolates men and women.

Michel, who wants to be an American, and Patricia, an American in Paris, reveal the inability of humans to connect in a modern, individualistic society. Michel claims to have a “feeling for beauty” and to love Patricia. In truth, his desires are libidinal and selfish; he mistakes eroticism for love and is left isolated. Patricia is more aware of her aversion to human connection, as she insists on her desire to be left alone and independent. The two exchange insults in their futile attempts at human connection. “You Americans are so stupid,” mocks Michel. “You adore La Fayette and Maurice Challe. And they’re the stupidest Frenchmen!” Patricia later replies, “the French are stupid, too.” Certainly, the two are not stupid. They engage the works of William Faulkner, Dylan Thomas, Renoir, Picasso, and Mozart, for example. These accusations rather suggest self-absorption. The two desire to have a monopoly on taste instead of valuing cultural exchange and the sharing of opinions in a public space. Here, Godard further depicts the selfishness of his characters while criticizing the apparently unstoppable hegemony of imported American mass culture, bent on dominating markets, not exchanging ideas. He also illustrates how Europeans and Americans create imaginaries of other nations, but in the end misrepresent each other. Underlying the exchanges is a desire to dominate instead of to share and understand. The couple come to this realization at the end of the film, when Michel confesses, “I just talked about myself, and you, yourself.”

The consequences of this imagined individualism are dire: Patricia shuns any opportunity for love and connection and Michel is betrayed by the one he loves. He is literally and figuratively shot in the back. The two are unwilling or unable to love; their loneliness prevails. Godard implicates American society in his character’s’ selfishness, naïveté

, and impoverished views of happiness and independence. Like Patricia and Michel, Americans are shaped by mass culture, isolated by modernity, and left lonely in futile strivings for private happiness and endless entertainment. Americans only come to know themselves when it is too late–the owl of Minerva infamously takes flight at dusk. Michel only faces their self-absorption after Patricia has called the police. His conclusion that she, and the situation they created, are disgusting–in essence, a realization that they have become grotesques–come right before he is out of breath—au bout de souffle.

Americans can only come to understand their loneliness after it is too late to pursue human connection. The democratic spirit is too entrenched, the monstrous cosmos of late capitalism too ubiquitous, the forces of modernity too powerful to escape an incurable isolation.

An American audience, faced with Godard’s implication of the glorified loneliness of American society, can only respond, “C’est vraiment dégueulasse.”

[1] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (New York: Penguin, 2003).

[2] Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (New York: Penguin, 2002).

[3] Richard Pell, Not Like Us: How Europeans have loved, hated, and transformed American culture since World War II (New York: HarperCollins, 1997), 204-205.

Pell, Not Like Us, 208-210.

[5] Pell, Not Like Us, 254-255.

[6] Hannah Arendt, On Revolution (New York: Penguin, 2006).

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Noice! Well this feel-good essay got me thinking.

A few thoughts:

– it’s tricky to make Michel a stand-in for “Americans”; he is, after all, French; he mimics what he perceives to be American precisely because he is not American; his actions are more akin to the immigrant or the outsider; now yes, there are Americans who feel isolated, but that is not necessarily the same as those who have a strong desire for assimilation; the latter tends to come from those who are left out of “normal” America

– there is another interesting element here untouched, that is Michel’s self-loathing; no doubt it is related in part to his American fetishism (as witnessed in his lust for Patricia and despising of Paris girls), but it must go beyond that; one doesn’t adopt a new culture (foisted upon her/him or not) without repudiation of the predecessor (sincere or feigned); in Michel’s case, he has largely embraced a cultural imaginary of America (as you pointed out: the American gangster), but what was it about the French culture that was so repugnant?

– Michel’s fixation on American culture is the tragedy; it leads him to depravity; Godard treats Americanism like a sort of parasite, or demon, inhabiting the body of young Michel, perverting him; therefore, corrupt, he must be killed by the apparatus of justice and moral uprightness (the French police oddly enough) and return to a more suitable host: an American—thus at the end you have Michel’s idiosyncratic gesture mimicked by Patricia; thought of this way, one can begin to appreciate Pells’s point about the acceptance and rejection of European minds about Americanization (i.e. Europeans adopted some of the American Way, but flatly dismissed other aspects of it). So Michel is not necessarily the wonted, but a warning about becoming it.

– finally, what is American culture? How do we define it through the context of foreign eyes? Is it Mickey Mouse? McDonald’s? Is it M&M’s or Nike? Are these products of culture or capital? What do these things say about “being American”? Is the mass consumer culture industry really the sum of our ethos? What are the consequences if we accept this?

Thank you for taking the time to read and respond thoughtfully. Your thoughts have me thinking, too.

You make an important point that Michel cannot be a “substitute” American through which to understand American culture. I think he can serve as a “host”–I found your “parasite” metaphor helpful–of what aspects of American culture were exported and on display, and how they were perceived by a European audience.

I suggest Michel, then, can be a kind of mirror that reflects the darker sides of certain values prevalent in American culture. This is where I see Michel’s character as a cautionary tale against a self-imposed isolation in the pursuit of an American lifestyle. I suppose the irony is his pursuit of the American gangster way of life implies his rejection of French culture and position as an outsider admiring American culture, all of which leave him isolated.

What about French culture Michel finds repugnant is worth considering. What do you think Michel finds in American culture that Paris cannot offer? It must be more than the allure of cheap thrills–stealing cars and such. Perhaps Michel is driven by deeper, conflicting desires of independence and connection.

The question is also a reminder of Pell’s point that “Americanization” was not simply forced on European victims. Rather, European audiences welcomed large parts of American culture–music, movies, newspaper and journals–after World War II. The question, then, is why?

No doubt popular films provide a lens to understand a culture in a certain time.

In what ways do you think a blockbuster, in form and content, is limited in showing us what a culture is and what those who form it value? Here, we have a movie about movies.

I sure hope mass consumer culture industry isn’t the sum of our ethos. Adorno’s writing on the culture industry comes to mind, and I hope to spend more time with his work in attempting to untangle these questions. Perhaps something has gone wrong in our ways of living when we find ourselves struggling to distinguish between products of culture and capital. But culture has to be more than a panoply of manufactured goods sold to appease manufactured desires.

The piece is well argued, and Tocqueville and Weber are put to good use here. (That’s not necessarily to say they were right — Tocqueville’s view on the supposedly isolating effects of an ‘equality of condition’ strikes me as one of the less persuasive arguments in Democracy in America — but that’s not really germane to the essay.)

The riff on Arendt toward the end seems a little more forced. The moral (or one possible moral) seems to be that Patricia — who wants to be left alone, who wants to “sell the news but not be a part of it” — should, to find real happiness, return to the U.S. and join a social or political movement or find the closest equivalent to the classical agora, pursuing the Arendtian ideal of active involvement in public affairs. How likely is that? At least in Paris she’s trying to have a career, whereas, say, as a housewife in an archetypal postwar American suburb, she would likely be even more unhappy than she is in Paris. Must keep in mind, istm, that this movie was made in 1960, when the range of options for women in general in these societies was more constricted than it was 20 or 30 years later.

Thanks for taking the time to read, comment, and make me think.

I’m curious about your thoughts on Democracy in America. What about Tocqueville’s observation on the isolating tendency of democracy do you find unconvincing? How does his argument fall short to you?

I understand my application of Arendt feeling forced. I think part of the point is

that the “treasure” of the Revolution–embodied in empowering discussions in New England town hall meetings and engaging debates in congress–albeit idealized, was lost after the founding of a Republic that ultimately closed a public space in favor of private pursuits of happiness.

In that sense, Patricia cannot be expected to find public happiness in a political space that has been long closed (and, of course, would not have included her anyway in the 18th century).

Certainly, some of model of freedom in the context of community responsibility would be oppressive for a stereotypical suburban housewife in 1960. And I wouldn’t think moving back to the states to become an active member of her local Parent Teacher Association is much of a means toward true happiness in a political space either. This leaves me asking: Does Patricia have the opportunity for fulfillment beyond pursuing private happiness? Can she achieve an independence that is not at the expense of meaningful human connection?

Re Tocqueville: I should probably be a little more careful about making that kind of dismissive, parenthetical remark about a famous theorist’s views.

On the substance — as a general proposition it’s not clear why the absence (or loosening) of formal class distinctions necessarily should lead to isolation. “Aristocracy links everybody, from peasant to king, in one long chain. Democracy breaks the chain and frees each link.” (DA, Vol 2, Pt 2, Ch. 2) But maybe democracy leads to its own sorts of horizontal (as opposed to vertical) links. For instance, would Americans have had such an inclination to form voluntary associations (which T. is enthusiastic about) were it not for the breaking of the aristocratic ‘chain’ and its attendant formal responsibilities/obligations?

Also, T. himself arguably is of two minds about this question. After the statements in Vol 2, Pt 2, Ch 2 about the dangers of an isolating individualism, he writes a couple of chapters later:

“In the United States the most opulent citizens are at pains not to get isolated from the people…. They know that the rich in democracies always need the poor and that good manners will draw them to them more than benefits conferred. For benefits by their very greatness spotlight the difference in conditions and arouse a secret annoyance in those who profit from them. But the charm of simple good manners is irresistible.”

So, on the one hand, democracy (or ‘equality of conditions’) breaks links between people, weakens their emotional ties to ancestors and descendants, and tends to isolate them from their contemporaries. On the other hand, “the rich in democracies always need the poor” — i.e., they need the poor, at a minimum, to accept the existence of the rich — and thus the rich “keep in constant contact” with the poor, displaying or using “the charm of simple good manners.” So democracy both isolates people *and* leads the rich to be “in constant contact” with ordinary people. True, both things could be going on at once, but there does seem to be a tension in the argument(s) here.

There are many brilliant insights in DA, but maybe some of the generalizations don’t always hang together quite as well as they might…

[quotes here are from the George Lawrence translation]

Jordan,

I apologize in advance for my lengthy response. But these aren’t the easiest/simplest topics for me to sum up in a few pithy sentences.

Needless to say, you’ve written a fine think piece and I look forward to seeing what else you come up with in the future.

Re: French culture, I wouldn’t be surprised if you are right that there is something about the idea of “independence” that appeals to Michel; France was still capable of being “medieval” in some respects (eg. women couldn’t vote until after the War and whatnot). There does seem to be something about bootstrap derring-do that compels people to try their luck on the American shores.

I can’t say much about the French culture, though, and that is more to my point. If the movie is our main source material, I don’t think Godard supplies a good answer for why Michel rejects the French culture; it is one of the more frustrating aspects of an otherwise delightful film, a film that is ostensibly about the preservation of “Frenchness” by warning of the American menace, but at no point is the audience given any sense of what is being lost (other than our lives!) if we accept Americanism; we are left to infer (I guess) that there is something great about French culture not worth losing; I just don’t know what that is; so my point in bringing it up initially was more a critique of Godard than your analysis—but he’s long dead, so all I have is this lovely essay to vent my opinions…

Re: American culture, my thoughts on the culture/capital struggle were purposely vague, but I think you’re on the right track; I see the negative dialectic? (meh, let’s stick with it since I already invoked the Frankfurters last time) play out in a way that ties nicely with your thoughts here on Michel; let’s use the mirror example (that’s good), you state it “reflects the darker sides of certain values prevalent in American culture”—what exactly are these “darker sides”? It can’t be the consequences of American vice; grand theft auto, rape, murder and all the rest of it was going on in France long before American culture came along and ruined everything; as you say, Michel is “a cautionary tale against a self-imposed isolation in the pursuit of an American lifestyle.” OK, so then these darker sides are expressed through the isolation felt while on the hunt for the American lifestyle; but what are these lifestyles? To get to the point, how does Michel experience American culture? On the silver screen. To go back to what I posted initially, Michel is acting on a “cultural imaginary” that he has embraced. I used “cultural imaginary” (in part because I stole and modified it from Charles Taylor, but also) because it is an imagined representation (on first glance by Godard, but ultimately by American movie studios) of the American Mind; so… are the “darker sides” from certain “values” of American culture, or are they the manifestations of corporate producers? I think there is a difference.

This boils down to: “how do we define a culture?” (or more precisely, how do we define this thing we call “American culture”?) Something I’ve been beating my head against a wall for quite some time. As you understand, culture is a very hard thing to pin down. No single temperature of the ocean, by Jove! That sort of thing. But people can’t truly experience something nebulous like culture unless they are there exposed right in the middle of it—even then I’m not too sure of it. So movies of any caliber fail to capture cultures, especially when the means (storytelling) is closer to an end of capital accumulation (not to say we can’t enjoy blockbusters, I think this is where Adorno and I part ways—Teddy! forgive me!) but if there is some “there” there to American culture, we cheapen it through the capital process; so you end up allowing Warner Bros., Walt Disney, McDonald’s, Capitol(!) Records, etc. to become the curators of “America” to the masses for the sole purpose of their profit; if we accept this, we’ve already given up vital ground (many, mind you, have no problem with this), and it’s already too damned loose as it is! So how do we make the distinctions? Well, that’s a tough circle to square. It’s very difficult to bifurcate American culture from capitalism (especially after post-War consumer culture), you know what I mean?

A few other thoughts that just popped into my head while writing this:

– if I remember the Pells book correctly, which I probably don’t (it’s been a while), he was getting at this (i.e. Europeans were willing to embrace many aspects of American culture, but were most leery of this commercialization and often made last stands to preserve their culture from capital’s [or American modernization if we want to call it that] overhaul, commodification, and wholesale auctioning of it)

– what I remember irritating me most about Michel was his two-dimensional qualities; at first, I chalked it up to less-than-great writing, then I began to realize it spoke more to what Godard was thinking about while he wrote Michel than the writing necessarily

Anywho, good work. I’m glad to chat about this more at length if you care to: iaian.blair.2011@gmail