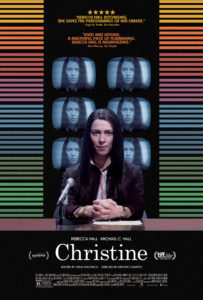

Perhaps because last year was an unusually good one for film, the movie Christine largely fell under the radar.[1] Christine is a biopic about Christine Chubbuck, the local TV newscaster in Sarasota, Florida, who shot herself in the head during a newscast on July 15, 1974, becoming the first person to ever commit suicide on live television. Chubbuck’s suicide became a national news story at the time, helped inspire Paddy Chayefsky’s screenplay for Network (1976), and was, oddly, also the subject of another film that was released last year, Kate Plays Christine.[2]

Perhaps because last year was an unusually good one for film, the movie Christine largely fell under the radar.[1] Christine is a biopic about Christine Chubbuck, the local TV newscaster in Sarasota, Florida, who shot herself in the head during a newscast on July 15, 1974, becoming the first person to ever commit suicide on live television. Chubbuck’s suicide became a national news story at the time, helped inspire Paddy Chayefsky’s screenplay for Network (1976), and was, oddly, also the subject of another film that was released last year, Kate Plays Christine.[2]

The film Christine manages to avoid two obvious potential pitfalls of a film about Christine Chubbuck: pat biopic clichés and a lurid focus on Christine’s death. In fact, very little is known about the real Christine Chubbuck. Footage of her suicide, though rumored to exist, has never surfaced. Very little footage of her other television work apparently survives. And the private Christine Chubbuck remains a mysterious figure. Christine‘s screenwriter Craig Shilowich has compared the process of writing the character of Christine to the Jurassic Park‘s imagined recreation of dinosaurs from drops of blood found in insects encased in amber.

Out of the shards of available material about Chubbuck’s life, Shilowich, director Antonio Campos, and Rebecca Hall, who plays Christine, managed to create a subtle and searing portrait of mental illness. Shilowich imagined Christine‘s title character as both bipolar and, perhaps, suffering from a form of borderline personality disorder. Hall plays her in a way that is simultaneously off-putting and deeply sympathetic. But in addition to being an effective character study, Christine is also a film that explores a particular milieu at a particular time, a local TV newsroom in the mid-1970s. And I am going to focus on Christine‘s image of the 1970s in this post.

***

Earlier this week, Andy Seal blogged about changes he sees in the historiography of the 1980s. While once historians of that decade focused on Ronald Reagan and the rise of the right, Andy sees neoliberalism emerging as a new focus for historians of that decade, displacing Reagan and the right. It’s an interesting argument and, to be honest, I’m still mulling it over, both as a description of what’s going on in the historiography of the ’80s and an argument about what ought to go on in that historiography.

But Andy’s argument has interesting implications for the historiography of the 1970s, the decade on which I’m currently working. In recent years, interest among historians in the 1970s has soared, as that decade has come to be seen as the watershed from which the United States of the 1980s and beyond, what Dan Rodgers has labeled the Age of Fracture, emerged. The election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 is still treated by most historians of the 1970s as a key marker of that arrival. And yet, the accounts of the 1970s provided by historians like Jefferson Cowie in Stayin’ Alive and the late Judith Stein in Pivotal Decade, both books that are now seven years old, can be read as narratives of the arrival of a neoliberal order (a term Cowie uses, but Stein does not). The historiography of the 1970s suggests that we don’t necessarily need to choose between seeing the 1980s as the Age of Reagan or seeing it as the beginning of the neoliberal order. From the point of view of the 1970s, at least, the 1980s looks like both; perhaps they are the same thing.

***

If much of the historiography of the 1970s focuses on the emergence of the 1980s, perhaps unsurprisingly, that historiography has often also focused on the relationship of the 1970s to the 1960s. Many historians of the 1970s have seen that decade as a kind of retreat from the 1960s, a curdling of that earlier decades hopes or even a backlash against it. Just this year, however, Judy Kutulas has argued in After Aquarius Dawned that the Seventies might better be seen as a kind of fulfillment of the Sixties, a time when many important strains of the counterculture went mainstream and permanently transformed American life.

Taken together, these apparently competing narratives – Seventies as backlash against the Sixties and Seventies as fulfilment of the Sixties’ counterculture – seem to set up Andrew Hartman’s understanding of the culture wars of the later twentieth century as an extended argument over the Sixties and their legacy.

Kutulas’s Seventies are a time of hope, liberation, and improvement in American life. The cover of her book features an image, immediately recognizable to anyone who lived in that decade, that captures these themes nicely: the smiling face of Mary Tyler Moore as she tosses her hat in the air during the title sequence of the Mary Tyler Moore Show, a program which, like Christine, was set in a local TV newsroom in the 1970s, though one in which its lead character achieved self-fulfillment, despite its challenges. Katulus’s vision of the decade stands in contrast with the often grim portraits of the Seventies provided by other historians who focus more on inflation, the oil crisis, Watergate, and so forth. After all, Philip Jenkins titled his book about America from 1975-1986 Decade of Nightmares (2006).

Kutulas’s Seventies are a time of hope, liberation, and improvement in American life. The cover of her book features an image, immediately recognizable to anyone who lived in that decade, that captures these themes nicely: the smiling face of Mary Tyler Moore as she tosses her hat in the air during the title sequence of the Mary Tyler Moore Show, a program which, like Christine, was set in a local TV newsroom in the 1970s, though one in which its lead character achieved self-fulfillment, despite its challenges. Katulus’s vision of the decade stands in contrast with the often grim portraits of the Seventies provided by other historians who focus more on inflation, the oil crisis, Watergate, and so forth. After all, Philip Jenkins titled his book about America from 1975-1986 Decade of Nightmares (2006).

These competing historiographical strains are matched by the heterogeneous ways in which the 1970s is depicted in more recent works of popular culture. Sometimes the 1970s are brightly colored, silly, and innocent, as in That Seventies Show (1998-2006) or Anchorman (2004), sometimes they are grim and depressing, as in Zodiac (2007). Sometimes the grimness of the 1970s and its bright, bell-bottomed culture can be mixed and matched as in Dick (1999), the satire which Rick Perlstein has called the best film about Watergate.

Even in the Seventies, one person’s party was another’s culture of narcissism. For millions of women, the arrival of no-fault divorce laws (the first one in the nation was signed into law in California in 1970…by Ronald Reagan) meant freedom; for Tom Wolfe it was one of the signs of an empty “‘Me’ Decade.”

***

Let’s finally return to Christine and its portrait of a Sarasota TV station in 1974. [Warning: spoilers follow]. Michael Nelson (Tracy Letts), who runs the newsroom, has recently embraced the idea that “if it bleeds, it leads,” urging his news team to pursue ever more sensational stories. Christine stands among her coworkers out for her intelligence and often bluntly critical perspective. She wants to report significant stories with rich human content, not just sensational ratings-grabbers. But Michael treats her with explicitly sexist disdain. Early in the film, the station’s out-of-town owner, Bob Anderson (John Collum), comes to Sarasota, apparently looking for talent with which to stock the newsroom of his new station in Baltimore, a much bigger market. While Christine chafes at her station’s demand for sensationalism, she also wants to get ahead. She buys a police scanner in the hopes of pursuing stories more in line with Michael’s desires. And she secretly longs for the company of George Peter Ryan (Michael C. Hall), the station’s anchorman.

But Christine is a lonely and awkward figure, who lives with her mother and seems to have moved to Florida after some kind of breakdown while working for a station in another state. After Christine yells at her boss, Michael, for refusing to run a story she’s produced, George appears to ask her out on a date. But it turns out that he wants to help her by introducing her to an encounter group that he attends. She also discovers that George has been asked to come to Baltimore. Christine works up the courage to ask Anderson, the station’s owner, about whether she can go to Baltimore with him, which she does by visiting him, unannounced, in the middle of the night claiming that she’s had a flat tire. Anderson, slightly drunk, is happy to talk to Christine, but he tells her that, at George’s suggestion, he’s already hired Andrea (Kim Shaw), “that little blonde number in sports.” Though we don’t yet know it, Christine appears to begin plotting her on-air suicide at this point.

In many ways, the world of Christine resembles the world of Anchorman, the hit comedy set in that very same year, 1974, in a local television newsroom across the country in San Diego. Both depict newsrooms in which a woman is the best journalist, but has to battle against the sexist condescension of the men in her office, in which sensationalism is coming to dominate local news, and in which on-air talent struggles to receive the recognition that will lead to career advancement.

But the two films present this common world in utterly different ways. Anchorman, fast-paced, upbeat, colorful and funny, presents the world of 1970s local news as a bygone age, even the sexism of which can be seen, retroactively, as hilarious. Of course, the film is told from the point of view of its male characters. Christine, in contrast, is slow-paced and grim. Even its color palette is muted. Like Anchorman, Christine plays up its Seventies setting. The film opens with Christine filming herself sitting at an otherwise empty table conducting a mock interview with Richard Nixon. The technology of the TV station, the design of clothes and furniture, the encounter group that Christine attends at George’s insistence all are distinctly of their time. But while Anchorman presents the Seventies as a bygone era, unlike our own. The Seventies in Christine feel more like the beginnings of our world, the emergence of the neoliberal order.

Rather than ending with Christine shooting herself on camera, the film concludes with a wonderfully resonant epilogue. Christine’s cameraperson Jean (Maria Dizzia), whose career seems to be advancing during the movie as Christine’s stalls, travels in the ambulance to the hospital with Christine and, after Christine is pronounced dead, returns home. Earlier in the film, Jean had reached out to Christine after her confrontation with their boss, suggesting that the two leave work and do what Jean always does when she feels stress: eat ice cream and sing along with whatever song is on the radio. Though Jean is presented as much less lonely figure than Christine earlier in the movie, we have never seen her entirely away from work. Now, having returned from the hospital alone, Jean serves herself a dish of ice cream as Ford’s statement on the pardon of Richard Nixon blares from her tv in the background.[3] She changes channels on the TV (all we see is static) and sits down to enjoy her ice cream. As we see Jean sitting in the dark eating her ice cream, the familiar theme from The Mary Tyler Moore Show emerges from the television off screen. Jean sings along: ” “Love is all around, no need to waste it / You can never tell, why don’t you take it / You might just make it after all / You might just make it after all.” The show begins off-screen, Jean’s face becomes more pensive and as she continues eating her ice cream, and the film comes to an end.

___________________________________

[1] So much, in fact, that it received the Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association’s 2017 Dorian Award for Most Unsung Film of 2016. At the time of this blogpost, the film is available on Netflix streaming. I highly recommend it.

[2] This quasi-documentary follows the actress Kate Lyn Sheil preparing to play the role of Christine Chubbuck in an apparently fictional film about Chubbuck.

[3] This is a bit of a cheat on the filmmakers’ part, as Chubbuck killed herself in July 1974 and Ford made this speech in October of that year.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I am definitely going to see this movie, thanks for this overview!