Try to tell the story of America’s drive for liberty from two battered silver teaspoons. Toggle between an eight-year-old’s question about New England’s colonial slaves, and a veteran teacher’s query about the Declaration’s oddball archivism. Pilot classes through the ratification debates, antebellum reform movements, and get to the Civil War by lunch. Public history is nonstop teaching. We work with and for visitors to reinvent the syllabus daily. After nearly a decade of work at the Massachusetts Historical Society—the oldest organization of its kind in America—I’d like to reopen the public history playbook and talk pedagogy. How and why we should teach the American past (especially narratives of war and peace) in museums, libraries, archives, and galleries is rarely part of the graduate history curriculum. Yet, our humanities hubs often serve as arenas for some of our most difficult social dialogues. Rangers and curators impart much of the same survey material that professors do, by working on a different canvas. Functioning as the world’s classroom, public history deploys manuscripts and artifacts, piling the past onto your weekday. War stories—even sagas as well-documented as the American Revolution—flex to undergo our modern rewrites. Working with their audiences, public historians who retell stories of revolution and civil war must find an ideological key to put artifacts in context. I start small, with a spoon or two, and build.

Try to tell the story of America’s drive for liberty from two battered silver teaspoons. Toggle between an eight-year-old’s question about New England’s colonial slaves, and a veteran teacher’s query about the Declaration’s oddball archivism. Pilot classes through the ratification debates, antebellum reform movements, and get to the Civil War by lunch. Public history is nonstop teaching. We work with and for visitors to reinvent the syllabus daily. After nearly a decade of work at the Massachusetts Historical Society—the oldest organization of its kind in America—I’d like to reopen the public history playbook and talk pedagogy. How and why we should teach the American past (especially narratives of war and peace) in museums, libraries, archives, and galleries is rarely part of the graduate history curriculum. Yet, our humanities hubs often serve as arenas for some of our most difficult social dialogues. Rangers and curators impart much of the same survey material that professors do, by working on a different canvas. Functioning as the world’s classroom, public history deploys manuscripts and artifacts, piling the past onto your weekday. War stories—even sagas as well-documented as the American Revolution—flex to undergo our modern rewrites. Working with their audiences, public historians who retell stories of revolution and civil war must find an ideological key to put artifacts in context. I start small, with a spoon or two, and build.

History and memory have long been flashpoints of inquiry for this scholarly community. I look forward to the conversations that we’ll have in October on that theme (Huzzah, USIH colleagues, on your acceptances! Stay tuned right here to the blog for all conference news). As part of prepping for our public history plenary, I’ve been mulling over the kind of intellectual history involved in curating and presenting “history’s stuff” to the public. Material culture embodies ideas, and trying to trace evidence of one big-ticket concept—in this case, liberty—means threading together a layered set of artifacts that show-and-tell how people thought and acted in the past about it. By choosing objects, we pick voices. In setting up the narrative, we might move around plotlines, try on a local accent, or distort old landmarks. As we curate, the news beats on. Confederate statues fall; descendants of Montpelier’s enslaved families excavate the past; and once again, congressmen brawl on and off the front page. It is a busy time to be a public historian, ready to interpret “how people thought about X” for exhibit labels, docent tours, teacher workshops, class trips, and tourists. When it comes to storyboarding “grand narratives” like the Revolution or the Civil War, finding a resonant balance between history and memory can be a challenge.

Sacrifice, as Robert Greene eloquently reminded us, is shaded and shaken up by memory. Public historians, too, deal in kaleidoscopic views of the past, and must stand ready to stir conversation about the bits we don’t always plan to discuss. There is no easy, no “best” way to record a war or to reckon with its monuments. As debates raged over marble men, I dug through the stacks preparing a show-and-tell on the American Revolution’s relics. I scoured the MHS collections trove for juicy manuscripts and artifacts alike, identifying 5 (!) objects to tell the familar saga to a lively group of k-12 students and parents in under an hour. (The “sequel,” after a quick coffee break, was the Civil War). My pop-up exhibit, meant to depict the changing idea(l) of liberty, magnetized to a New England perspective.

Whenever I do this presentation, I change up the objects, so the larger story shifts, too. I’ve included a mini-gallery, above and below, of the American Revolutiom in 5 objects. Selecting a fair range of manuscripts and objects to frame a conflict is always a struggle. With that in mind, I invite your ideas on the topic of how we interpret artifacts of war, and include a diverse set of voices, in public history practice. When did seeing the “stuff of history”—especially the material culture of war—really change your view of the past? Which objects would you use to show/tell a new intellectual history of the Revolution?

The World of the American Revolution in 5 Artifacts

- The Revolution lands on Boston’s doorstep: Miss Relief Ellery (later Vincent), a 20-year-old Charlestown resident, grabbed these dainty silver spoons (above) from the breakfast table, fleeing to the woods when the British began firing on her town. When she returned, her entire home was gone. The spoons were all she had left. Both ordinary and extraordinary to see, they help to sketch the backdrop of daily life in 1770s Boston, and to orient the Battle of Bunker Hill as a turning point.

- What do you do in a city under siege?: Young Connecticut militiaman Samuel Selden, encamped at Roxbury, inscribed his powder horn with this rich map of Boston. Note the Continental Army’s fortifications, and his proud rhetoric: “Made for the Defence of Liberty.” Reading Selden’s gear gives us a window onto militia life, and puts print culture’s power in clearer perspective. Plus, that lion!

After the siege, the drive for liberty: Abigail Adams’ 31 March-5 April 1776 letter to John, then at the Continental Congress, is a vivid example of her revolutionary reportage. She laments Boston’s “ravages” following the British evacuation. Then, in the next breath/page, she forges on to list what she’ll plant at the farm and blueprints what the new federal government should look like. (Hint: “Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors”).

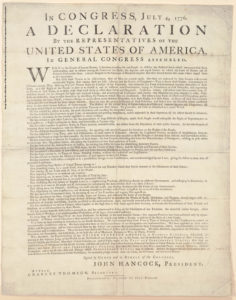

After the siege, the drive for liberty: Abigail Adams’ 31 March-5 April 1776 letter to John, then at the Continental Congress, is a vivid example of her revolutionary reportage. She laments Boston’s “ravages” following the British evacuation. Then, in the next breath/page, she forges on to list what she’ll plant at the farm and blueprints what the new federal government should look like. (Hint: “Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors”). What does liberty sound like?: Take a look at one of the rare first printings of the Declaration of Independence, a broadside issued by John Dunlap of Philadelphia. This is a chance to talk about natural rights, what’s left in/out; how founding documents were drafted and edited; and why we celebrate on the Fourth of July. (No treasure map on the back, alas). We may not think of the Declaration as an artifact of war, but reading it aloud (and focusing on the ferocity of the verbs) can shift that, allowing us to experience the manuscript as a set of bold ideas in action. Liberty feels urgent.

What does liberty sound like?: Take a look at one of the rare first printings of the Declaration of Independence, a broadside issued by John Dunlap of Philadelphia. This is a chance to talk about natural rights, what’s left in/out; how founding documents were drafted and edited; and why we celebrate on the Fourth of July. (No treasure map on the back, alas). We may not think of the Declaration as an artifact of war, but reading it aloud (and focusing on the ferocity of the verbs) can shift that, allowing us to experience the manuscript as a set of bold ideas in action. Liberty feels urgent.- What comes next?: Still glinting, George Washington’s gilt lamé-and-yellow-silk epaulets, worn at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781 and turned in to Congress two years later, always incite a slew of questions (above). Unlike Relief Ellery, he needs little introduction, so I ask visitors for three quick ways to describe him. Last time, I heard: “He owned slaves.” “He was a farmer.” Pause. “And he was a general.” There’s a capsule historiography evident in the hierarchy of those replies. Washington’s retirement (and return to federal service) caps off the mini-exhibit by striking a thoughtful tone: Who won liberty in the Revolution, and at what cost?

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Great post

For Revolutionary “stuff”, I’ve never actually seen any actual artifacts in person. However, I do recall, as a child, being told the Betsy Ross story while the teacher passed around a replica of the flag. Even though I knew it wasn’t the actual flag, I did have a sense of holding history. It was more real than, say, having a copy of the Declaration in my hands.

Of course, nowadays, what I find more interesting about her story and the flag is the degree of historicity (or lack thereof). It speaks to how the Revolution is subsumed into this national lore. Yes, Betsy sewed our nation’s first flag, Molly Pitcher fired the cannon and Washington chopped that cherry tree down, etc. I suppose every nation needs its Romulus and Remus.

The first historical experience I had, though, was with the Civil War at Gettysburg. Standing by that wide open field of Pickett’s Charge, holding one of those three-ring bullets in my hand. That was some real stuff.