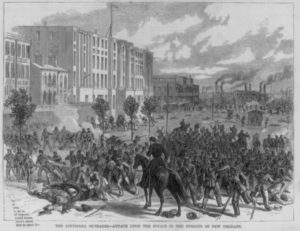

The bringing down of a nineteenth century moment dedicated to white supremacy and terrorism in New Orleans last week has reminded all of us of the ways in which Civil War and Reconstruction still loom large in American memory. Arguing over old neo-Confederate monuments, or state support for flying the Confederate flag, has a new lease on life in both an “Age of Trump” and an “Age of Black Lives Matter.” That the nation is at a crossroads of race and memory right now—just as the United States wrestles with both the legacy of Barack Obama and the presidency of Donald Trump—is not a surprise. But events since the Charleston massacre of 2015 prove that the debate over memory in American society is never-ending.

Media coverage of the event, to an extent, shows how this fight over memorialization is one that will continue for the long term. References to the monument as a “Civil War” memorial or a “Confederate” memorial are wrong

. The monument, dedicated to the Battle of Liberty Place in 1874, reminds us of the destruction of Reconstruction governments across the South. That this was done through terrorism and the murder of Republican officials and African American men and women was valorized by monuments such as the one recently removed in New Orleans.

So, no, this is not a “Confederate” monument. But it is, for all intents and purposes, a reminder of how the United States lost the peace after the Civil War.

Mississippi, meanwhile, continues a debate over the inclusion of the Confederate battle flag in its state flag. A debate that began in 2015, just as South Carolina was taking down its Confederate flag on the statehouse grounds, Mississippi’s debate is an even fiercer version of the debates about the flag and its symbolism that have raged on and off in states such as Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina for decades. Remember that Mississippi’s state flag has had the same design since 1894. The Lost Cause has a hold on Mississippi that will not be easy to shake—recall the uproar that took place when the University of Mississippi took down the state flag in 2015 (and Mississippi State and other state schools there followed suit).

Memory occupies an important part of the American civil religion. As with any other nation, the myths and legends we tell us are a part of what makes America “America” are crucial to understand. Confederate flags represent an understanding of American history that erases Reconstruction, deifies belief in the Lost Cause, and obscures the political problem of slavery as the chief cause of the Civil War. I am unsure of how much longer the Confederate flag, Southern monuments, and other representations of a white supremacist view of the past will be with us. But it will be a long, tiring campaign to save a different, more honest interpretation of the past for future generations.

One merely wishes each Confederate monument could be replaced with that of a Southern Unionist, African American soldier, or a Reconstruction-era African American politician. An honest, forthright conversation about the monuments and flags that are with us is, currently, the best we can hope for. And the most we can fight for.

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thank you, Robert. Let’s hope this can happen. As you say, it’s going to take a long time. It can only be somewhat different depending upon where one is in the South I guess? It’s weird living in Nashville now, where the old communities, buildings and homes are being bulldozed with something like alacrity every day, and where the Tennessee legislature just surreptitiously commemorated Nathan Bedford Forrest at the same time. http://wreg.com/2017/04/26/tennessee-lawmakers-unwittingly-vote-to-honor-nathan-bedford-forrest/

I was teaching V.S. Naipaul’s Turn in the South (1987) for the umpteenth time recently and I was struck again by how much he dropped the ball or didn’t see so many things. I hope sometime we can talk about that book. I’d like to know what you make of it if you’ve had the time to read it between having to read so many other things. To my mind, for what it’s worth, Naipaul made so many fruitful connections with a global South, but too often in passing and not always in a good way. He tried to work out better landscapes of Southern memory at the start after talking with Albert Murray, but then got caught up in twee white Southernisms for a while (fascinating–to him–white “redneck” culture) only to lapse into what might be called a lament for a communal South of faith and memory that never came together in the book, as if it could or should.

Yet, I was struck this time by how his last chapter “Smoke” is suggestive, in that if taken as a metaphor seems to be saying something. As an elegy for North Carolina tobacco culture, metaphorically speaking he suggests that the South of memory and commemoration celebrates labor and artisanal ways of life, yet all of that dedicated to a poisonous leaf that killed so many. (To play it out some more: older forms of work against industrial capitalism and the service economy–yet older forms of work tied to the idea of the Lost Cause or misguided moonlight and magnolias agrarianism.) The problem is that he just leaves the metaphor there without any serious consideration for unpacking it more. Maybe he means to say that the problem is that white Southern partisans for the Lost Cause don’t seem to understand that their identity, in the terms you mention, is killing them as moral human beings. The trouble in the 21st century is that many of the most cutthroat free market partisans are also white Southern memory partisans. He seemed to see that even thirty years ago, yet he left it mostly unremarked, as is his way, just leading a horse to water, all suggestion, allusion and no conclusions.

Maybe this makes Nashville a cautionary note: tremendous growth, pockets of hyper-individualistic wealth, non-stop gentrification, blue political pockets ringed round by reactionary politics of a toxic variety. I can only imagine the many observations of a thoughtful man living in Columbia, SC. I figure it has its own valences over there. So thanks for this. As we know, there’s more to say.

Thanks for the great comment–and I need to read Naipul’s book again. When I first read it a few years ago I also believed there were some things that needed a different frame of analysis from what he argued, but I couldn’t quite put my finger on it at the time.

And you’re exactly right. When it comes to talking about these monuments, where one is in the South also changes the conversation. So, just as the debates might look different in South Carolina versus Tennessee, so they’ll look different in Atlanta as opposed to rural Georgia, or Charlotte against Western North Carolina, and so on.

Thanks for this post, Robert. Like you, I’m monitoring this national discussion of memory closely. And you know I’ve been outspoken advocate that those memories need their own Reconstruction period. A revision of whitewashed monuments is a first step in that process. – TL