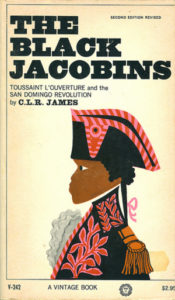

Two of the greatest history books ever written emerged three years apart: W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America (1935) and C.L.R. James’s Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution (1938). Both were about race, class, slavery, and revolution, and both were forged with comparable purposes. Du Bois and James sought that their historical insights about revolutions past would speak to revolutions future.

Two of the greatest history books ever written emerged three years apart: W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America (1935) and C.L.R. James’s Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution (1938). Both were about race, class, slavery, and revolution, and both were forged with comparable purposes. Du Bois and James sought that their historical insights about revolutions past would speak to revolutions future.

Du Bois, the most important African American intellectual of the twentieth century, wished for his trailblazing analysis of the Civil War and Reconstruction to endow the wisdom of past struggles upon the coming movement for black rights in the United States. James, a Trinidadian living in London at the time of writing and one of the most important intellectuals of the twentieth-century black diaspora, hoped that his remarkable inquiry into the Haitian Revolution would speak to the emerging anticolonial movements for independence in Africa.

The similarities between Black Reconstruction and Black Jacobins do not end there. Both books have been comparably received since publication. Although black and left-wing audiences read and praised these books immediately upon publication, not until the 1960s did they reached large mass audiences. By that point many more people were ready to accept the radical conclusions drawn by Du Bois and James. It was then that Black Reconstruction

won its place as arguably the single most important book in reshaping American historiography with regards to the Civil War, Reconstruction, slavery, the South, race, class, and civil rights. It was also in the 1960s when Black Jacobins was heralded as the formative text in the growing international study of the African diaspora.

There is more. Both Du Bois and James wrote their canonical studies with Marx on their minds. As I have previously argued here at the blog, Black Reconstruction was great at least in part for its Marxism, however eclectic and expansive. The same was true of Black Jacobins. C.L.R. James’s was helped by Marx—and he also expanded upon Marx in a way that gave twentieth-century readers a new and better understanding of capitalism and capital formation, one that more fully accounted for the plunders of slavery and colonialism, what Marx called primivite accumulation.

Black Jacobins reads like a drama—a tragedy, really—which is not surprising given that in 1934 James wrote a three-act play about Toussaint, which played in London and starred Paul Robeson (how I wish it were on YouTube). Towards the end of Black Jacobins, as the story of the Haitian Revolution is reaching its climax, James writes: “There is no drama like the drama of history.” One of the appeals of Marx to many twentieth-century thinkers has been the way in which Marx’s theory of history is dramatic. I was turned on to this notion by one of favorite interlocutors at this blog, Richard King, who wrote the following in a comment to a previous post about the Marxist canon: “the other great book of the 1930s that lasted to be learned from by Marxists and non-Marxists alike is CLR James’s The Black Jacobins. It was important particularly in the 1960s. I sometimes think that Marxism is most compelling as a way of capturing the drama and struggle of modern history, as articulated in terms of class struggle but not confined to those terms strictly speaking, since, in James’s case, Toussaint was as important a force for change as the race-as-class struggle.”

Indeed so. James toggles between thinking that events determine humans, and that humans determine events. For him Toussaint is a great man in the Whig sense. Born a slave, he made himself into arguably the greatest revolutionary leader in the Age of Revolutions. “Yet Toussaint did not make the revolution. It was the revolution that made Toussaint.” So it seems Marx spoils the Whiggish fun—but perhaps not, as James follows this line with a curious qualifier: “And even that is not the whole truth.” Even that is not the whole truth.

Indeed so. James toggles between thinking that events determine humans, and that humans determine events. For him Toussaint is a great man in the Whig sense. Born a slave, he made himself into arguably the greatest revolutionary leader in the Age of Revolutions. “Yet Toussaint did not make the revolution. It was the revolution that made Toussaint.” So it seems Marx spoils the Whiggish fun—but perhaps not, as James follows this line with a curious qualifier: “And even that is not the whole truth.” Even that is not the whole truth.

James lays out his theory of history in his introduction to Black Jacobins. “Great men make history,” he writes, “but only such history as it is possible for them to make. Their freedom of achievement is limited by the necessities of their environment. To portray the limits of those necessities and the realisation, complete or partial, of all possibilities, that is the true business of the historian.” Upon reading this, it seemed to me beyond any doubt that James was channeling Marx from the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.” Such influence would hardly have been surprising given that James was a committed socialist revolutionary who often called himself a Leninist.

My strong suspicions were confirmed later in the book when James quoted from the Eighteenth Brumaire at length: “Upon the different forms of property, upon the social conditions of existence as foundation, there is built a superstructure of diversified and characteristic sentiments, illusions, habits of thought, and outlooks on life in general. The class as a whole creates and shapes them out of its relationships. The individual in whom they arise, through tradition and education, may fancy them to be the true determinants, the real origin of his activities.” In other words, the history of slavery and colonialism and resistance gave shape to Toussaint and the Haitian Revolution. Yet even that is not the whole truth

.

Aside from the introduction, Black Jacobins mostly reads like a dramatic narrative history of the Haitian Revolution. Narrative that is jaw-dropping exciting and makes for a great book on its own. But to me, the greatest quality of Black Jacobins are the lightning bolts of historical wisdom that James nonchalantly drops into the narrative here and there. A few samples, ranging in length:

The struggle of classes ends either in the reconstruction of society or in the common ruin of contending classes.

No place on earth… concentrated so much misery as the hold of a slave-ship.

The difficulty [in owning slaves]…was that… they remained… quite invincibly human beings….

The cause in each case [comparing 1775 San Domingo to 1938 Germany] is the same—the justification of plunder by any obvious differentiation from those holding power.

The slave trade and slavery were the economic basis of the French Revolution.

When did property ever listen to reason except when cowed by violence.

It was the quarrel between bourgeoisie and monarchy that brought the Paris masses on the political stage. It was the quarrel between whites and Mulattoes that woke the sleeping slaves.

The rich are only defeated when running for their lives.

Revolution, says Karl Marx, is the locomotive of history. Here was a locomotive that had travelled at remarkable speed [since the storming of the Bastille]…

The struggle of classes ends either in the reconstruction of society or in the common ruin of contending classes.

It is the privilege of historians to be wise after the event, and the more foolish the historian the wiser he usually aims to be.

Pericles on Democracy, Paine on the Rights of Man, the Declaration of Independence, the Communist Manifesto, these are some of the political documents which, whatever the wisdom or weaknesses of their analysis, have moved men and will always move them, for the writers, some of them in spite of themselves, strike chords and awaken aspirations that sleep in the hearts of the majority in every age. But Pericles, Tom Paine, Jefferson, Marx and Engels, were men of a liberal education, formed in the tradition of ethics, philosophy and history. Toussaint was a slave, not six years out of slavery, bearing alone the unaccustomed burden of war and government, dictating his thoughts in the crude words of a broken dialect, written and rewritten by his secretaries until their devotion and his will had hammered them into adequate shape. Superficial people have read his career in terms of personal ambition. This letter is their answer. Personal ambition he had. But he accomplished what he did because, superbly gifted, he incarnated the determination of his people never, never to be slaves again.

It is Toussaint’s supreme merit that while he saw European civilization as a valuable and necessary thing, and strove to lay its foundations among his people, he never had the illusion that it conferred any moral superiority.

Many an honest subordinate has in this way been the unwilling instrument of the inevitable treachery up above; the trouble is that when faced with the brutal reality he goes in the end with his own side, and by the very confidence which his integrity created does infinitely more harm than the open enemy.

I won’t go into detail about the actual historical narrative here, nor will I judge how it stands relative to more recent historiography (As Kevin Gannon wrote on Twitter: “it may be blasphemous to say as a historian, but James’s book is one of those that’s truer than the truth.”) I encourage everyone to read the book and judge for themselves. I will close, however, by saying that this book more than any other I have ever read unfolds history as a series of possibilities. Given the cruelties of slavery and colonialism, it is inevitable that the history of Haiti would be written in blood. But it did not have to be quite so tragic.

11 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Eric Brandom pointed out to me elsewhere that the first James quote above–“The struggle of classes ends either in the reconstruction of society or in the common ruin of contending classes”–is from the Communist Manifesto. He is of course correct and I am ashamed that I did not recognize that. James does not put the passage in quotation marks–the Communist Manifesto was in the public domain for a Marxist thinker like James–but I should have recognized as much.

At least you knew it was a good idea. Great essay. Bringing TBJ on the plane with be tomorrow.

“There is no drama like the drama of history,” but I am always fascinated at the narratives historians emphasize and those they do not. Historians of the U.S. tend to overlook the story of the Haitian Revolution because it doesn’t neatly fit into the traditional political history narratives of the 1790s and 1800s.

The “aristocratic” John Adams has a much more racially progressive foreign policy towards Haiti and its vanguard of Black Jacobins than his successor, the “apostle of liberty,” Thomas Jefferson. Adams and his Secretary of State Timothy Pickering break bread with Toussaint L’Ouverture’s emissary Joseph Bunel an are unperturbed by his marriage to Marie Bunel who was a free Creole. The Republicans who have just a few years earlier had argued for the recognition of Citizen Genet as a representative of the revolutionary government, are now balking at recognizing Haiti and Bunel as an emissary.

The Federalists who abhorred the political violence of the French Jacobins are rather sympathetic to the notion of a successful slave revolt. The Republicans? Not so much. Albert Gallatin abhorred a revolution led by “men who received their first education under the lash of a whip, and who have been initiated to liberty only by that series of rapine, pillage, and massacre, that have laid waste to that island in blood; of men, who if left to themselves, if altogether independent, are by no means likely to apply themselves to the peaceable cultivation of the country, but will try to continue to live, as heretofore, by plunder and depredations.”

The past decade or so has seen an increase in the number of journal articles and monographs dealing with the Haitian revolution which should lead to more accurate interpretations of the history of the early republic.

I’m not familiar enough with the historiography to comment on it. But the US plays an interesting side role in The Black Jacobins. In an effort to frustrate the French and to make a profit, it seems the Americans sold arms to the San Domingo rebels. James has some hilarious commentary about English and American hypocrisy regarding free trade and slavery.

Those interested in following up some of these issues might look at David Scott’s “Conscripts of Modernity: The Tragedy of Colonial Enlightenment”. Since I did the book on “Arendt and America,” I should note that Scott criticizes Arendt, rightly, for having analyzed the American and French Revolutions as the two originary landmarks of political modernity in “On Revolution”, while neglecting to mention Toussaint and the Haitian Revolution. (Arendt did welcome the Cuban Revolution for a while and was at Princeton when Castro came there to speak in the late 1950s.) Crane Brinton’s mainstream “The Anatomy of Revolution”, which was so broadly influential up into the 1960s, paid scarcely any attention to the Haitian case; nor did the more radical Barrington Moore’s “Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy” even include Haiti or Toussaint in its index. I should say that Scott does go on to observe that Arendt nevertheless identified the tragic situation of revolution in the modern world, which was forced to choose between the creation of the institutions and ethos of political freedom and the creation of greater economic equality under centralized control, usually at the expense of political freedom. James’s “The Black Jacobins” is a kind of exemplary account of just such a tragic unfolding of historical events and forces.

Not as knowledgeable as I should be about the Haitian Revolution, but it’s not clear to me how it would have fit into Moore’s concerns in Social Origins (which is not necessarily to say he was right to omit any mention of it). Moore’s book is not a survey of revolutions but in large part an examination, as its subtitle suggests, of the role played by peasants and agrarian conditions and landlord/peasant relations in the modern (i.e., up through mid-20th century) political trajectories of England/Britain, France, Russia, China, India, and Japan.

Historiographical currents change, as they should, and whereas these days most any general discussion of the French Revolution will probably include some mention of the roughly contemporaneous Haitian Revolution, and though Hobsbawm mentioned the Haitian Rev. in his 1962 The Age of Revolution, I suspect that it was less common in the mid-’60s, when Moore published Social Origins, to mention the two together than it is today.

As far as Brinton’s Anatomy of Revolution goes, haven’t read it but based on what I understand to be the character of that book, I’d think the criticism of neglecting Haiti has somewhat more force w/r/t Brinton than Moore. But the Brinton was published even earlier, so the neglect is not too surprising.

So CLR James drops in these larger, more philosophical observations as his own (except where specifically stated otherwise)? Does the book have an extensive notes apparatus, linking to philosophers, etc.? …It sounds aphoristic–given in a Nietzschean fashion. – TL

Aside: Kloppenberg covers Toussaint and the Haitian Revolution in the chapter I’m reading on the 1789-1793 portion of the French Revolution.

Tim: the book is well sourced. James uses footnotes, mostly primary sources, and the book includes a nice little bibliographic essay at the end. But aphorism is also a feature.

Per Brian’s comment above…I dunno — maybe it’s just because I’m re-reading History’s Memory, so am especially skeptical just now regarding “old history”/”new history” claims, but I’m not convinced that US historians still “overlook” the Haitian Revolution. Recent survey textbooks I’ve looked at/used give a fair amount of space not just to the Haitian Revolution as a phenomenon, but to the different policies and sympathies of Jefferson, Adams and George Washington in relation to the long struggle for freedom in Haiti, as well as to the anxieties of the planter class about revolutionary news and revolutionary influences reaching their own enslaved labor force from the influx of “refugee” planters from Haiti.

Whatever has made its way into the survey textbooks put out by the major publishers is, arguably, “mainstream” historical thought. And of course CLR James is one of the reasons that the Haitian Revolution has a secure place within the “coverage” of the survey. But I’d be quite surprised if most American historians today (or, for that matter, in earlier periods) were in fact surprised to learn the different positions of Adams and Jefferson.

Having done a good amount of research on the Haitian Revolution and its reception in US academia, I think LD’s impression is on point in regards to the increased attention that the Haitian Revolution and Hait has received. But I am not sure this attention is connected to The Black Jacobins itself. I would link this surge of interest to the emergence of postcolonial sudies in the US and, particularly, to Michel Rolph Trouillot’s 1995 classic, Silencing the Past, which opened the floodgates to numerous monographs dedicated to the Haitian Revolution and its reverberations across the region and in the US.