Guest post by Chris Arnold.

Over 30 years ago, Chuck Reilly, a recently retired steel executive had a problem. In the scope of his personal life history of serving and losing a brother in the Pacific, rising from labor to management and raising 7 children (including one with special needs) it was not one of the more important ones. However, in the moment, how to entertain or rather distract his 3 grandsons of 6, 5 and 4 on a quiet Sunday afternoon was a crucial issue. After some negotiating (a skill sharpened by his years as the Foreman of bar finish at Crucible specialty metals) he had Chris, Mike and Jason all situated around his easy chair. He began, “a long time ago some explorers were looking for oil, they heard about a possible oil well on a pacific island so they got a boat and sailed there…” and within a few minutes his problem was solved as the boys were regaled the American myth of King Kong.

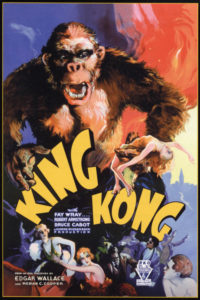

Few memories of my childhood have such a strong or even obsessive hold as the first time my grandfather (who a few generations earlier, would’ve been a shoe-in for the village Seanchai) retold the story of King Kong. I’ve been thinking a lot about that incident as the latest cinematic iteration of the Kong myth, Kong: Skull Island premieres this week. While this new Kong movie can be explained by yet another case of Hollywood’s mining of our collective nostalgia for products to sell or as South Park Memorably and wickedly satirized  it “member berries

it “member berries

,” I would argue the Kong movies differ in significant ways from the other franchises of the current pop culture scene. In fact I’ve been revisiting some thoughts I’ve had for a while on what exactly is the Kong myth and how it works in 20th century American culture. Since the original 1933 movie roughly every 20 years has seen a major cultural reproduction of the Kong myth. 1954’s Creature From the Black Lagoon

, Dino DeLaurentis’s remake of the original King Kong in 1976, Disney’s 1993 Beauty and the Beast, 2005’s Peter Jackson remake and now finally Kong: Skull Island

.

In each instance, using the fairy tale archetype of the Beauty and the Beast, twentieth century popular cultural producers fashioned a uniquely American text that not only delineated but reinforced and in rare occasions transgressed cultural discourses of violence, history, gender, beauty, monstrosity and racial other. This myth was so powerful that it escaped the fetters of its original medium (as the above personal and anecdotal evidence suggests) and has become a colossus that stalks the 20th and 21st century American cultural landscape. It is, to use Lawrence Levine’s phrase, a major element of Industrial era folklore.

While I’m far from the first person to write analytically about Kong, I think there remains a great deal to be said. Following the intellectual trail blazed by Richard Slotkin, I hope to excavate roots of the Kong myth’s cultural genealogy, then, through an examination of the producers of each text of the Kong myth as well each text itself hope to demonstrate that the myth of Kong and its uses are as beneficial to understanding American culture as the myth of the Frontier has been for earlier periods of American history.

Chris Arnold has an M.A. in history from SUNY Brockport. He is an independent researcher and historian. His most recent project involves editorial and research assistance on Dr. John P. Daly’s forthcoming history of Reconstruction as a southern civil war. Areas of research interest include American cultural, religious, and political history.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Chris, I am *so excited* about this upcoming series. When I saw the trailer for the newest Kong, I thought, “Someone should really write about why King Kong, of all things, is the one movie that always gets remade.” I am so glad you are doing this!

Why does Hollywood trot out Kong for every generation, and why is it always so awful? (Or is it that all the “monsters” get a remake every era — Frankenstein, Dracula, the Mummy, etc — and Kong is just an awfully American monster?)

Anyway, can’t wait to read these posts!

It is interesting that you fold Beauty and the Beast into this genre. When the new live-action version of the Disney movie (which I haven’t seen) came out and Emma Watson was in it I thought maybe they’d do something transgressive with it, like have the beast turn out to be black. No such luck. But apparently the story has worked on my unconscious. I’m looking forward to seeing what you do with this!

Chris,

Thanks for this interesting post.

Barbara Creed has also written about Kong (from the perspective of evolutionary theory) in a chapter from her Darwin’s Screens (Melbourne University Press, 2009). She notes that, “[l]ike the classic Beast of the ‘Beauty and the Beast’ tale, Kong dreams of finding a mate, an exotic Other who is very different from himself. . . . Once worshipped by primitive people as a deity, Kong is sacrificed by the civilized world to a god beyond his comprehension. Kong’s fall from deity to demon parallels the journey of the animal and its role in human history—an important theme of the 1976 remake of King Kong” (Creed, 182).

I find it interesting how the size of Kong seems to increase throughout the years, although this might be due to the advancement of CGI rather than any sociological insight (maybe the continuing residue from Jurassic Park?).

It seems like some cultural and intellectual systems require the combatting of an Other to sustain their existence. From what I’ve seen of the recent trailer (“It’s time to show that man is king”), there’s also the continuing theme of justifying a distorted, post-Darwinian chain-of-being through the physically-enhanced features of “monsters” (size and strength) that force humans to band together under the imperative of survival at all costs.

apologies for the delay in my reply. Thanks for all the positive comments. I think, as I hope future posts will demonstrate , that what I call the King Kong Myth is an American version of the multi cultural folk tale motif of the Beauty and the Beast. By incorporating various critical cultural discourses, in my view the Kong myth is one of the most significant and useful pop culture myths of the Twentieth Century.

1) L.D. And Eliza I hope I will justify your faith in future posts on such a fun topic.

2) Mark some interesting thoughts and thanks for the heads up about the Creed essay.