It is easy to underestimate the significance of James Fenimore Cooper for American literature and American imagination more broadly. To the modern reader his prose appears tedious, his characters shallow, and his plots formulaic. Even when compared with contemporaries he at times appears as a clumsy curiosity: he lacked the wit of Washington Irving or the psychological penetration of Charles Brockden Brown. He did, however, demonstrate an uncanny ability to cater to the sensibilities of an American audience thirsty for cathartic formulas that could elevate the American settler-colonial project to the realm of the mythological—despite festering moral equivocations. Indeed, in many ways Cooper pioneered the themes later taken up not only by Emerson and Whitman, but also by more critical authors such as Melville, Twain, and Faulkner.

Born in 1789, James Fenimore Cooper’s peculiar personal background seemed to endow him with the intellectual and emotional confusion necessary to unearth and explore many of the challenges at the heart of a congealing American culture. Cooper grew up in a wealthy and genteel household surrounded by frontier common folk. Although his father, William Cooper, raised him in a firm Federalist environment, by the time he published his first important novels in the early 1820s Cooper joined the ranks of his father’s former political adversary, Governor De Witt Clinton. Expelled from Yale at the age of sixteen because of a prank, Cooper joined the merchant marine as a sailor and later the US Navy, viewing the world from a much different vantage point than most other young men of his social milieu. Although when his father died in 1809 he supposedly left him a great fortune, J. F. Cooper soon learned of the estate’s very tenuous financial standing as it came crashing down on his head. In fact, he started writing to help support his family as he sought to settle debilitating debts. In short, when at the age of thirty he started work on his second novel and the first of his novels set in America—The Spy, published in 1821—Cooper was uniquely attentive to a wide spectrum of the predicaments Americans of his generation wrestled with.

It was two of his next novels, however, The Pioneers

and The Last of the Mohicans, published in 1823 and 1826, respectively, that delivered the most mesmerizing and long lasting impressions of America. Casting the American West in romantic and sublime terms, they no less importantly also furnished American audiences with an exemplary model of frontier nobility in the immortal figure of Natty Bumppo. In The Pioneers Cooper portrayed the setting of his childhood in Cooperstown on the New York frontier, though he garbed it in fictive names. It was a narrative of the oncoming of civilization at the expense of nature. In the The Last of the Mohicans he used the historical setting of the Seven Years’ War to weave a narrative of the borderlands, in which settlers and Indians sought to navigate the natural environment.

Cooper organized both narratives in a similar formula that related the passing of the noble and sublime and the ascendence of white Anglo-American civilization. In The Pioneers the wild environment receded and with it the august figure of Natty Bumppo, the old frontiersman who could not live in a civilized setting. In The Last of the Mohicans, Uncas, the noble Mohican warrior, last survivor to a noble stock of Indian chiefs, died and with him the person the reader might have hoped could be his spouse, the character Cora, whose partly African heritage made her much “better fit” to marry an Indian. In both cases, however, Cooper mixed sadness and grief with hope, as two white couples of upright character united in marriage to symbolize the virtuous future of the nation under a regenerated yeomen patriarchy. In The Pioneers Oliver Effingham, a man of genteel background yet virile character, and Elizabeth Temple, the genteel and kind daughter of Judge Marmaduke Temple, inherited a vast estate. In The Last of the Mohicans the kind-hearted Alice Munro, Cora’s fully white half sister, united with the gallant Major Duncan Heyward and hinted at a bright future for white folks in America.

Indeed in both cases Cooper deftly designs a catharsis that finds acceptance in tragic closure. The reader mourns the demise of the wilderness and its inhabitants yet accepts it as necessary. Cooper invokes a compelling mythic formula to resolve the challenges intrinsic to the advent of the settler-colonial republic—namely, the brushing away of the genocide of Natives and the destruction of the natural environment.

Critical to the success of this schema, Cooper pioneered a mythic structure that combined the historical nationalism of Walter Scott in his numerous novels of Scotland and England with the Daniel Boone narratives first tried out by John Filson in 1784 and later modified by several others. Furthermore, though Cooper crafted the character of Natty Bumppo in many ways along the lines of Daniel Boone in Filson’s narrative, perhaps his most clever move was to invoke through the noble frontiersman’s character the godly persona of Jesus Christ. Natty Bumppo—the somber, selfless, and tortured figure who lives with the Indians as a Christian. Bumppo, who has many names, Leatherstocking, La Longue Carabine, Hawkeye, and in later books more still, transforms the narrative of regeneration into a more attractive mythological formula—as far as Cooper’s evangelically-inclined American audience was concerned. Thus, in Cooper’s gripping mythology, Natty Bumppo, a person “without a cross” in his blood—as he reminds us time and again—carries the figurative burden of the Christian cross, disappearing along with the sins of white civilization and leaving white Christians to inherit the American environment.

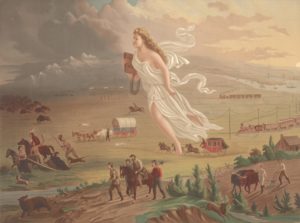

Indeed, what Cooper—probably subconsciously—recognized was that an “American Adam,” was not quite as compelling without an ‘American Jesus’ to clear the way. For Americans to construct a “passing away” of Native American civilization they were best served by a godly character that could function as a “sponge” for their sins, who could then disappear into the sublime. In this manner the people of the United States, who not incidentally at this very moment were undergoing religious evangelical revivals, could become a Christian nation with Native Americans playing the role of the old people of Israel who, tragically, could not adhere to the teachings of Christian civilization. In mythological terms it proved far more useful for the Daniel Boone mold of the stoic frontiersman to disappear from the scene rather than function as the offspring of American civilization. In this vein, the white pioneers that would start American civilization were more of the Peter and Paul variety than in the mold of Adam or Abraham, as some literary scholars have had it. This was the synthesis of providential nationalism and romantic language that two decades later would become known as “Manifest Destiny.”

After completing The Last of the Mohicans, in 1827 Cooper published the last book in the Leatherstocking trilogy, The Prairie (at least for the time being, he would return to Natty Bumppo fifteen years later). Close to death at the age of eighty, Cooper brings frontier civilization in the shape of an extended family of white frontiersmen to bask in Natty Bumppo’s glory one last time. When they first set eyes on him alone in the wilderness, the Bush family recognize a figure, “as it were, between the heavens and the earth.” As we follow the ebbs and flows of a borderlands narrative set on the western side of the Mississippi, Bumppo reforms the morals of the Bush clan, bringing them to the Christian path of righteousness before taking leave of this world. In his wake, we are made to understand, will arrive a better sort of white people who will transform the wilderness into civilization, as it must.

10 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Eran, what an intriguing reading.

FWIW, in the 1980s, American literature survey courses in (some) U.S. high schools began with the Knickerbockers. In other words, Cooper — not CBB nor Rowson nor Hannah Webster Foster — was presented as the first (great) American novelist, the first novelist worthy of notice.

I would give my eye teeth to figure out the title/edition of the American Lit survey textbook used at my high school, but (IIRC)JFC (!) was treated as the “first” American novelist — if not first in time, then first in importance. We didn’t read Last of the Mohicans, but we learned who Natty Bumpo was. For us, American literature began with Cooper, Irving, and Bryant.

Why we didn’t begin with Brown or Fowler is an interesting question, but I think it probably has a lot to do with ideas of “the American Renaissance,” and the aim of finding precursors to the same.

Thanks LD! It’s pretty much a condensed version of the last pages of my dissertation.

I agree, I think that it makes perfect sense considering that schools are such important vehicles for nationalist indoctrination. Cooper–and Washington Irving’s post 1820 work–provide a much easier and neat starting point, than CBB for example, whose work is much less digestible though I think he is one of the most original authors to ever work in the United States. That is also why Rip Van Winkle is far more celebrated than “A History of New York,” which is an amazing gem.

If you haven’t already try d.h. lawrrence’s studies in classic american literature, finder’s return of the vanishing American, and for a laugh twain’s literary offenses of james fenimore cooper. Pioneers oh pioneers!

Thanks, yup I read both and have appreciated both much more than Cooper’s writing, which I can’t stand, although I think its brilliant in its own way.

Thus, in Cooper’s gripping mythology, Natty Bumppo, a person “without a cross” in his blood—as he reminds us time and again—carries the figurative burden of the Christian cross, disappearing along with the sins of white civilization and leaving white Christians to inherit the American environment.

Not sure I get the reference to “‘without a cross’ in his blood” — did JFC mean to convey with that phrase that Bumppo wasn’t a practicing Christian?

Most interpretations take it to mean that he is white and does not have a cross in his blood with Indians, despite living with Indians much of the time.

I think that there is also something else here, that has to do with his Jesus-like role as well.

Thanks; I wasn’t reading “cross” in that sense, but I now get it.

barbara mann of the university of toledo wrote a paper entitled “man with a cross: hawkeye was a half breed” if that helps

I really enjoyed this post, it helps to clarify the meanings of Cooper, especially from the perspective that I am most familiar with: the circulation of his texts in 19th century Latin America, how his politics and aesthetics were appropriated to convey fantasies of white nationalism and civilization in the new nations to the south. The Brazilian writer José de Alencar’s Iracema and O Guaraní have been read alongside Cooper’s fictions of frontier culture and imperialism. In Facundo: or, Civilization and Barbarism (the foundational text, if there is any, in Latin American lit), Argentine writer Domingo Sarmiento borrows freely from Cooper’s works in order to posit, again, a narrative of racial cleansing, with the romanticized gaucho standing for the stoic frontiersman–in fact, Sarmiento participated actively in this process, as president of Argentina. Doris Sommer writes about this quite a bit in one of the better chapters of Foundational Fictions, she incorporates Lawrence and Fiedler in her analysis. Anne Brickenhouse’s book Transamerican Literary Relations and the Nineteenth-Century Public Sphere is worth checking out too, for how it investigates the reception of Cooper among Cuban writers. Interestingly, Cooper supported the study of Spanish and Hispanic / Hispanic American cultures, although this is something I am not much familiar with. Irving and Bryant are the ones usually mentioned in this regard.

Thanks Kahlil! This is a really interesting angle. I’m especially curious about Brickenhouse’s book, I should check it out.