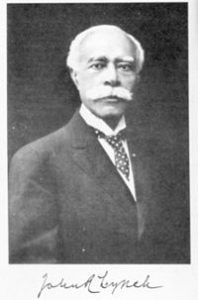

The fight over Reconstruction historiography traditionally begins with the Dunning School of the early twentieth century. That school of thought, out of Columbia University, argued that Reconstruction was a national tragedy and proved that African Americans were not fit to be American citizens. Often, the first stand against the Dunning School is seen in W.E.B. DuBois’ Black Reconstruction (1935). When it was released, the book was recognized for offering a stinging challenge to the then-prevailing thought on Reconstruction. However, we should also look to earlier works by African American scholars that also challenged ideas of Reconstruction. This is where the former politician John Roy Lynch comes in.

Lynch was an African American politician from Mississippi. Serving in the State House of Representatives (and as the first African American Speaker of the House in Mississippi’s history in 1872) and later in the United States Congress, Lynch had a unique perspective on the events of Reconstruction. In his The Facts of Reconstruction (1913) Lynch used both his political experience and training as a scholar to craft a history of the Reconstruction period that countered the prevailing theme of Reconstruction history that was accepted as gospel by most Americans. Lynch would also write “Some Historical Errors of James Ford Rhodes” for the Journal of Negro History in 1917—again, as an attempt to offer a corrective to the mainstream view of African Americans as either  incidental to or, more often, a hindrance on, the American Republic in the past and present. This is part of what Stephen G. Hall in Faithful Account of the Race (2009) as part of a revisionist wave of history written by African American historians in the early decades of the twentieth century, spearheaded by Carter G. Woodson.

incidental to or, more often, a hindrance on, the American Republic in the past and present. This is part of what Stephen G. Hall in Faithful Account of the Race (2009) as part of a revisionist wave of history written by African American historians in the early decades of the twentieth century, spearheaded by Carter G. Woodson.

His book is a fascinating read. It offers both what was, for the time, a fresh take on Reconstruction, and a political memoir of a man who recognized that African Americans would have to fight for political and social rights in the South for a long time to come. Lynch’s work is part of a tradition of African American counter-historiography—existing alongside American historiography—that tried to battle the attempts of mainstream history to condemn African Americans as being unworthy of citizenship. Additionally, at the end of his book, Lynch argues for what the Republican Party needs to do to help African Americans in the South.

In fact, if one were interested in reading about the history of the Republican Party during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, you could do worse than reading Lynch’s book. His “insider” status as a member of the Republican Party during and after Reconstruction means that Lynch had access to many of the important players in the party at that time, such as Grover Cleveland and James G. Blaine. Lynch’s critique of William Taft’s “Southern Policy” in the 1910s is a reminder that the Republican Party flirted with gaining the support of white Southerners long before the “Southern Strategy” of Richard Nixon in 1968, or even Dwight D. Eisenhower’s victories in Upper South states in the 1950s. The Door of Hope: Republican Presidents and the First Southern Strategy by Edward O. Frantz (2011) goes into considerable detail on this.

Lynch cared greatly about the future of African Americans in the South. He wrote a prophetic take on the future of the South, and African Americans:

If there is ever to be again, as there once was, a strong and substantial Republican party at the South, or a party by any other name that will openly oppose the ruling oligarchy of that section,—as I have every reason to believe will eventually take place,—it will not be through the disposition of federal patronage, but in consequence of the acceptance by the people of that section of the principles and policies for which the National Organization stands. For the accomplishment of this purpose and for the attainment of this end time is the most important factor. Questionable methods that have been used to hold in abeyance the advancing civilization of the age will eventually be overcome and effectually destroyed. The wheels of progress, of intelligence, and of right cannot and will not move backwards, but will go forward in spite of all that can be said and done. In the mean time the exercise of patience, forbearance, and good judgment are all that will be required.

Lynch argued that, sooner or later, the South would be changed by African Americans. It would merely need a political party to change with them, and take up the fight for civil rights on a national level. Writing at the height of the “nadir” of African American history, voices such as Lynch were important to keeping the flame of African American freedom and a more accurate history of Reconstruction alive in the fact of white supremacy and historiographic terror in the academy.

John Roy Lynch was part of a burgeoning school of thought that went against the Dunning School of Reconstruction. Scholars such as Lynch, along with William Sinclair and his The Aftermath of Slavery (1905), tried to give the recently freed African American men and women struggling to survive during Reconstruction voice in the history of an era that is still, to this day, poorly understood by most Americans.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Had Du Bois and Lynch’s paths ever crossed during their lifetimes? Or is there any indication in ‘Black Reconstruction’ that Lynch’s works had an influence on Du Bois?