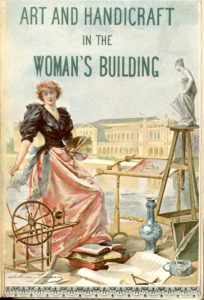

Phillis Wheatley walked the White City, thanks mainly to the black women of Pittsburgh. A bronze bust of the colonial-era poet, contracted by a local group of women citizens and crafted by African-American sculptress Edmonia Lewis, gazed out at the World’s Fair of 1893. The Paris-trained Lewis reduced her usual fees to finish the commission. “This is indeed a little history, and always to be remembered,” she wrote of recreating Wheatley. Around Wheatley, in the Woman’s Building, roughly 200,000 attendees came in waves. In a show of intellectual citizenship that amplified new political needs, American women gathered to hear a global congress of speakers address them in the poet’s shadow. Six African-American women leaders, all presidents or pioneers in diverse fields, stood ready to take the Chicago stage and talk history. Today, resuming my series on early American women intellectuals, let’s see another set of founders step out of their frames and speak.

By May 1893, a national spotlight already followed educator Anna Julia Cooper, who capped her early teaching career with a master’s degree in mathematics from Oberlin. Fairgoers were likely familiar with Cooper’s first book, A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South (1892), her lectures promoting African-American citizenship and civil rights, and her work in co-founding the Colored Women’s League. More than a century later, Cooper’s Voice rings out as fiery, smart, finely edged. To start, she splays out the connective threads of Christianity, feudalism, and women’s influence in history. Where do we get our ideals of womanhood from, Cooper asks, and what price do women pay for building civilizations like America into empires? She hauls in Macaulay, Tacitus, and Emerson for reference. Yet Cooper’s urgent appeal, to improve African-American lives now through education, dominates every page. And her cause spans centuries. “I would beg, however…to add my plea for the Colored Girls of the South:—that large, bright, promising fatally beautiful class that stand shivering like a delicate plantlet before the fury of tempestuous elements, so full of promise and possibilities, yet so sure of destruction,” Cooper wrote. “Oh, save them, help them, shield, train, develop, teach, inspire them! Snatch them, in God’s name, as brands from the burning! There is material in them well worth your while, the hope in germ of a staunch, helpful, regenerating womanhood on which, primarily, rests the foundation stones of our future as a race.”

For the Chicago crowd, Anna Julia Cooper tallied victories and blueprinted new goals. She counted 25,530 “colored schools” in the United States filled with 1,353,352 students. Assessing the twin pillars of Providence and progress, Cooper reported that African-Americans held $25 million “in landed property for churches and schools.” Her snapshot census of African-American life, the kind of data often cached in the nineteeth century’s “colored conventions” movement, shaped Cooper’s lifelong intellectual commitments. Many milestones lay ahead for Anna Julia Cooper (1858-1964): a Sorbonne doctorate earned at the age of 67, followed by her presidency of Frelinghuysen University. “Let woman’s claim be as broad in the concrete as in the abstract. We take our stand on the solidarity of humanity, the oneness of life, and the unnaturalness and injustice of all special favoritisms, whether of sex, race, country, or condition,” Cooper told her growing sea of colleagues. “The colored woman feels that woman’s cause is one and universal.”

Inside the women’s pavilion, members of the women’s congress likely traded views on the gathering’s other intellectual draws, such as Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells. Along with Cooper, they heard five more black women redefine rights for the American Century. Many, like abolitionist and author Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, tried to place the whole World’s Congress of Representative Women in greater historical perspective. The prolific Harper (1825-1911) seized on the theme of “Woman’s Political Future” and advertised the merits of suffrage. “If the fifteenth century discovered America to the Old World,” Harper observed, “the nineteenth is discovering woman to herself.” Educator Sarah Jane Woodson Early

Inside the women’s pavilion, members of the women’s congress likely traded views on the gathering’s other intellectual draws, such as Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells. Along with Cooper, they heard five more black women redefine rights for the American Century. Many, like abolitionist and author Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, tried to place the whole World’s Congress of Representative Women in greater historical perspective. The prolific Harper (1825-1911) seized on the theme of “Woman’s Political Future” and advertised the merits of suffrage. “If the fifteenth century discovered America to the Old World,” Harper observed, “the nineteenth is discovering woman to herself.” Educator Sarah Jane Woodson Early

(1825-1907), who was named the “Representative Woman of the Year,” spoke proudly of local organizational efforts in Tennessee: “If we in the midst of poverty and proscription can aspire to a noble destiny to which God is leading all his rational creatures, what may we not accomplish in the day of prosperity?” Then, Early charged on: “Hark! I hear the tramp of a million feet, and the sound of a million voices answer, we are coming to the front ranks of civilization and refinement.”

Hallie Quinn Brown, an Ohio-born teacher who spent the 1870s teaching in Mississippi and South Carolina, followed up on the calls for reform laid out in Sarah Early’s speech. Brown had honed her oratory on popular topics of the day, arguing for suffrage and promoting temperance. By the time she took the platform in Chicago, Brown (1850-1949) worked in a prominent post, serving as dean of women at the Tuskegee Institute. A vocal opponent of the early plan to exclude African-American women from the exposition, Hallie Brown cut out her sentences with care. In her speech, Brown sought to expand the bounds of civic space. She recalled the 300 girls who saw her off, remarking that African-American women’s “development from darkest slavery and grossest ignorance into light and liberty is one of the marvels of the age.” Brown took time to highlight the labors of Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and William Lloyd Garrison. She pointed to “a life-size statue” of Wheatley, praising Edmonia Lewis for recognizing her own “genius within.” Art spoke volumes, but Brown also pushed her audience to consider the merits of learning basic household economy, and the significance of obeying the “gospel of honorable manual labor” in order to succeed. “What more is needed?” Brown asked. “Time and an equal chance in the race of life.” A groundbreaking leader of African-American women’s clubs who skillfully leveraged their political power, she later served as president of the National Association of Colored Women from 1920 to 1924.

As the congress wore on, more African-American women intellectuals filled the stage. Teacher and advocate Frances (Fannie) Barrier Williams (1855-1944) offered a striking model. Williams, who had studied at the New England Conservatory of Music and at Washington’s School of Fine Arts, was a leader of Chicago’s library and culture scene. She spoke on “The Intellectual Progress of the Colored Women of the United States Since the Emancipation Proclamation,” observing to her audience that, “Less is known of our women than of any other class of Americans.” African-American women, William said, were progressive, Christian, and interested in “fighting against the nineteenth century narrowness that still keeps women out of the higher institutions of learning.”

Frances (Fanny) Jackson Coppin, a former slave freed as a teenager for the price of $175, stepped forward to describe her work as a Pennsylvania school principal and as vice president of the National Association of Colored Women. Coppin (1837-1913), who taught Greek, Latin, and math, implored fairgoers to champion higher education for all. “If black girls can calculate equations and logarithms as I saw them doing yesterday, how much more could you with your higher inheritance do?” she asked. “Do you consider that you owe us an obligation for that?” As Coppin wrapped up her remarks, Frederick Douglass rose from the crowd, moving to add a lone male voice to the general congress’ official record. “I say there is a time coming when prejudices, discriminations, proscriptions, and persecutions on account of what is accidental will all pass away,” Douglass said, “and this great country of ours will be possessed by a composite nation of the grandest possible character, made up of all races, kindreds, tongues, and peoples.”

In the great shuffle following the world’s fair, Phillis Wheatley was lost. The bronze memento bust, swiftly and silently, went missing and sank into history. Here are six women worth reading and hearing, until, like Edmonia Lewis’ Cleopatra, we see her again.

- Check out Frances Harper’s 1892 novel, Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted, available to read here.

- Hallie Quinn Brown’s papers are open for research at Central State University.

- Read Fannie Barrier Williams’ A Northern Negro’s Autobiography and more in ed. Mary Jo Deegan, The New Woman of Color: The Collected Writings of Fannie Barrier Williams, 1893-1918 (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2002).

- Archives with research material documenting Fanny Jackson Coppin’s career include New York Public Library, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, Haverford College, and the African American Library and Museum at Oakland in California.

0