In 2007, Andrew Sullivan wrote a cover essay for The Atlantic in which he argued that the rise of Barack Obama to the national stage meant an end to the divisive cultural politics that defined American politics since 1968. Sullivan argued at the time, “he could take America—finally—past the debilitating, self-perpetuating family quarrel of the Baby Boom generation that has long engulfed all of us.” Reflecting on the events of the last eight years, it now seems this assumption about Obama’s rise was naïve and misplaced. Now, as we transition from an “Age of Obama” to an “Age of Trump” everyone has spilled much ink—both real and digital—trying to explain how we got here.

A keen reading of African American history, especially intellectual history, offers us much to consider in this debate. The recent Ta-Nehisi Coates essay, “My President Was Black,” offers one of the better meditations on Obama’s presidency and its possible legacy. The responses to it—in particular Tressie McMillian Cottom’s—have all been useful to also think about Obama’s failings and successes in office. Along with this is a reflection among historians and others about what kind of era we’re entering. Indeed, Coates’ body of work—from his essay on Bill Cosby and Black America

to this most recent piece—offer a fascinating take on post-1945 African American history. While I will leave that for another post down the road, I do want to tackle the ways in which history is being discussed in the public sphere in 2016.

Historical comparison is a cottage industry unto itself. After November’s election, pundits and historians alike began casting a wide net to make comparisons with the past. Jamelle Bouie compared the events of November 8, 2016 to the backlash to Reconstruction. This comparison soon caught on with other writers. Barret Holmes Pitner, at The Daily Beast, made a similar argument. In concern about potential backlash to racial progress, I can sympathize with this comparison. This reminds me of earlier comparisons made between Black Lives Matter and the Civil Rights and/or Black Power Movements. But I also vehemently disagree with it.

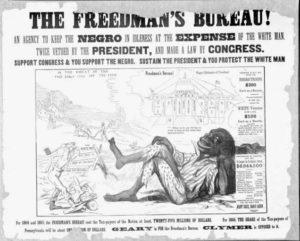

Backlash against racial progress is central to the story of America–as you can see with this political advertisement from 1866. Whether or not it was the reason for Trump’s victory, the interminable problem of racism and democracy in American society remains with us.

Historical analogies are useful, but we also need to recognize how they are limited in speaking to the present moment. Both Bouie and Pitner acknowledge this. History never repeats itself. It doesn’t even necessarily rhyme. But we can “use” history to think harder about the present. History, taught well, teaches us that the present is never easy to understand. There are never any simple answers or quick victories. Historical comparison, of course, is nothing new. C. Vann Woodward, among many others, referred to the Civil Rights Movement as a “Second Reconstruction.” Today, the theologian and activist Rev. Dr. William Barber of North Carolina refers to the present day as a “Third Reconstruction.” Others may also argue that the here and now is a “second Nadir of African American history,” in comparison with the low point in African American history from 1890 to 1930 written about and described as such by Rayford Logan.

The comparison with another nadir is not new. The historian Sundiata Keita Cha-Jua argued, in a The Black Scholar essay in 2010, that Black America was already suffering through a second nadir. There, he argued that African Americans were already in a nadir due to a variety of factors. Most notably, the changes in American political economy since the mid-1970s due to the rise of neoliberalism and its associated policies of austerity—coupled with cultural and political debates over colorblindness and racism—have damaged the progress made by African Americans in the immediate aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement. Cha-Jua argued that events such as the 2000 election (and allegations of voter suppression in Florida), the federal response to Hurricane Katrina, and the collapse of the housing market in 2007-08 (which destroyed the slowly-built up wealth of the African American middle class) were all symbols of the modern nadir. This was all before Obama’s election in 2008—which Cha-Jua argued was “contrasted but not off set by” the events previously mentioned.

I disagreed with this analysis of a “new Nadir” when it first came out. Today, I am tempted to argue that it is the best analysis of the present moment. Economic factors of the damage done to African Americans over the last three decades lend some credence to Cha-Jua’s analysis. And, to be blunt, I worry that any administration in the White House may not provide the answers to helping millions of Americans—regardless of race—recover from the 2008-09 Great Recession. The debate about voter suppression across the country, highlighted by recent events in North Carolina, also make the “new Nadir” take a tempting one.

I still reject a wholesale comparison with that era, for a variety of reasons. But it is not out of any sense that things are fine today. On the contrary. Historical comparisons are not to be discarded. They can and do serve a purpose. Comparisons across historical eras make the present day easier to understand. In that sense, African American history is critically useful. After all, African American history offers a bitterly learned lesson—that democracy and progress are always built in American history on a foundation of sand. Freedom cannot be taken for granted. Most importantly, the whiggish idea of history as a march of progress has been laid bare, once again. Much of human history proves this. For Americans, however, to simply look to the history of African Americans—or, for that matter, Native Americans, women, Hispanics, a multitude of groups—is to realize that “progress” and “hope” are not natural to human history.

And so we plunge into 2017, unsure of the future and groping for lessons from the past to help us. The urge to make historical comparisons is understandable. Just remember that the differences between eras is important too.

10 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Pleased to see you are challenging the “third Reconstruction” narrative Robert. It does not work historically. Reconstruction and the so-called Second Reconstruction were “progressive periods” 14th, 15th Amendments, 1875 Civil Rights Act, etc. in the first and of course the legislative victories of the modern civil rights movement in the second. This is not a period of “progressive” racial legislation. While I too am not completely comfortable with the “nadir” analogy, it does work better then “Reconstruction.”

Agreed. I think I get where people are coming from with a “Third Reconstruction” angle, but it doesn’t seem to work the more you compare the eras.

As always, thanks for reading.

Robert: this is such a beautifully written (if very painful) piece. I tend to think that the Trump election signifies the arrival of another nadir, as decisive an announcement as was Plessy. I hope I am wrong.

Thanks for the kind words. And that’s my biggest fear–there are some other parallels I barely mentioned here that scare me. But we shall see.

This is inspiring stuff, Robert! It left me thinking of the idea of tragedy (as well as hope) and its uses to frame history. It reminded me of the following: in his work on Caribbean ideas of revolution and anticolonialism, the anthropologist David Scott turns to the concept of tragedy as a productive way of questioning the tendency to romanticize anticolonial struggles–part of his focus is C.L.R. James’s classic, The Black Jacobins. But I also have issues with how the tragic can overdetermine both hermeneutics and political action and erase radical hope. Is there a way beyond the opposition between hope and the tragic? Thanks for making me think hard about these matters.

I’m glad you got so much out of my piece! I think there has to be some way between hope and tragic. Cornel West has often argued that the definition of “hope” should not be the same as, say, “optimism.” Here’s one place that gets into that–http://archerpelican.typepad.com/tap/2004/05/cornel_west_on_.html

You’re right, though, we both need to get beyond the conflict between hope and tragedy, as well as not allowing tragedy to swallow up current ideas of hope. You’ve given me something to also think–and perhaps write–about.

Robert, I was reminded of this post today as I’m prepping to teach Reconstruction tomorrow.

I always begin every class, every semester with a “why study history” intro discussion that inevitably gets around to the question of whether or not history repeats itself, how history could be predictive, etc, etc. And this semester was no different — though it has felt different.

I don’t think history is repeating itself. It may not even be echoing. It may simply be that an old impulse, once sidelined to some extent or driven underground, is re-emerging with renewed vigor.

That impulse, as near as I can name it, is “Redemption,” — that same shameless, corrupt, hate-fueled, racist (and sexist) backlash, contemptuous of law, devoid of ethics, bent on destroying the fragile institutions that (however imperfectly) seek to safeguard the civil rights and fundamental freedoms of citizens in a participatory democracy. And nothing and no one so far has been able to stand against this juggernaut.

It is enough to drive one to despair.

FWIW, here’s how I framed Reconstruction. Hardly original, but perhaps useful to those getting ready to teach it next week.

Reconstruction via Nast

Thanks for posting both these replies. I once, half-jokingly, suggested during a seminar years ago that we should probably begin to think of all of American history as white backlash–with some ebb and flow in there.

But in all seriousness, it is hard to square the history of the nation with any sort of interpretation beyond a fragile belief in democracy and freedom for all its people, often under siege from internal forces.

Thanks Robert.

I was just talking to a friend about how the first week went. (And because my institutions are staggered, “the first week” is also next week at the community college.)

I really hate having to start out the second half of the survey with Reconstruction. During the first half of the survey, you can trace out with your students the historical development of race-based slavery, the stratification of American society and the paltry compensation of “the wages of whiteness” as a wedge to make sure that the oppressed would never make common cause. Even that history, taught with perspicuity and thoughtful care, can be rough going with a class full of students who have absorbed an awful lot of Lost Cause / Redemptionist historiography in their K-12 education.

But to start right out in week one with Reconstruction and the Redemptionist backlash is such a tough assignment. My students haven’t learned yet that they can trust me, and the first thing they’re hearing from me is some Damn Ugly News. I haven’t yet figured out how to leverage this less-than-ideal situation and work within this dynamic. I’m not happy with how Thursday’s lecture went, so maybe the best thing to do is address that some on Tuesday while we’re talking about building the transcontinental railroad, exterminating the buffalo, and conducting genocidal wars against Native Peoples.

Bad news.