In the 1970s, in central California, some high school students read Pat Frank’s novel Alas, Babylon

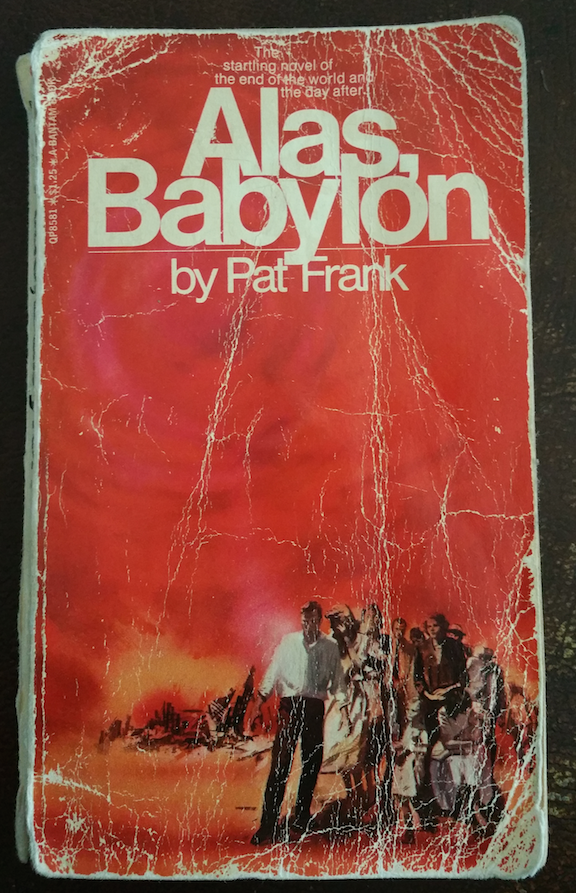

in their sophomore English classes. I know this because my grandmother, who went to college in her forties and earned a bachelor’s degree and became a high school English teacher in one of the little farm towns of Stanislaus County, assigned this book in her classes as part of that district’s standard curriculum. In fact, I think this is one of her copies – the 30th printing, hot off the presses of Bantam Books some time in 1974 or 1975.

First published in 1959, Alas, Babylon is a post-apocalyptic novel set in “Fort Repose,” a fictional rural community in central Florida. The premise of the novel is simple enough. Soviet nuclear missiles have struck the United States, including nearby MacDill Air Base. Infrastructure, food supply, law and order – all have been obliterated. The country folk and townspeople who survived the blast must now figure out how to survive the aftermath. They have to figure out not just how to find an uncontaminated water supply, how to find food, what to do in medical emergencies, but how to rebuild the social order: how to protect themselves from lawless outsiders, how to tell friend from foe, how to foster and defend a just and democratic society.

First published in 1959, Alas, Babylon is a post-apocalyptic novel set in “Fort Repose,” a fictional rural community in central Florida. The premise of the novel is simple enough. Soviet nuclear missiles have struck the United States, including nearby MacDill Air Base. Infrastructure, food supply, law and order – all have been obliterated. The country folk and townspeople who survived the blast must now figure out how to survive the aftermath. They have to figure out not just how to find an uncontaminated water supply, how to find food, what to do in medical emergencies, but how to rebuild the social order: how to protect themselves from lawless outsiders, how to tell friend from foe, how to foster and defend a just and democratic society.

And all the while they don’t know what is happening in the larger world. Have the Russians destroyed the United States? Is there a war on? Is anyone fighting back? Is America still standing?

One of the major motifs running through the novel concerns racism and discrimination. The basic takeaway, as you might expect, is that the white residents of “Fort Repose” – and, by analogy, white America (or, for mid-century readers, just “America”) – cannot survive without the help and knowledge of their black neighbors. In the face of an existential threat, it would be foolish, even suicidal, to cling to old prejudices. I’d say “spoiler alert” here, but is it really a spoiler to know that the plot requires that A Good Black Man Die Heroically and Selflessly in order to drive home to readers the message that We Are All Americans and We Must Defend Democracy Together?

In any case, the novel is an interesting artifact of its time; in a U.S. history survey it would pair well with a screening of Atomic Café. Indeed, despite the author’s stated intentions, outlined in a Foreword, to offer a glimpse of the “nature and extent” of the devastation that could be wrought by “the H-bomb,” the same naïve optimism that characterizes some of the Civil Defense clips featured in Atomic Café suffuses this novel too. I guess it would be hard to sell a post-apocalyptic novel whose premise was that nobody would survive the apocalypse.

Still, at first glance it strikes me as an odd reading choice for high school students in the late 1970s, in a school district in the central San Joaquin Valley, in the shadow of a Strategic Air Command base with a wing of B-52s that were taking off and landing at all hours, every day, all through the Cold War.

I was a high school student in the central San Joaquin valley in the 1980s, not the 1970s – different decade, different school district, but still well within the blast radius of whatever would have been launched against that base. And we all knew it. We all knew it. The scenario of The Day After

was terrifying – but even as we watched it on TV, we knew that we were watching somebody else’s story. If the Russians attacked, there wasn’t going to be a day after for us; when the Red Dawn came, we knew we wouldn’t be around to fight back.

I guess maybe that’s precisely why you would assign a book like Alas, Babylon to a bunch of high school students in a little farm town in the middle of California (or anywhere else) at the height of the Cold War (or any other time). Being able to think about the Worst, and then somehow imagine that you would still have to face the Day After That, is an important exercise. The point of post-apocalyptic fiction is never about surviving the apocalypse; it’s always about reflecting on what kind of society we are, or want to be. Maybe if we can figure that out, we can find a way to avoid the apocalypse.

That was a worthwhile thought exercise in the 1970s in California, even in the hinterlands of the San Joaquin Valley – indeed, perhaps especially there. And though it’s not great literature by any stretch, Alas, Babylon was probably a fairly engaging and accessible read for high school students toiling through sophomore English.

I would be interested to know how this particular text fit into the larger curriculum, and if I have the chance, I’ll try to do some archival research on this question. Was Alas, Babylon understood as “dated” when the students read it? Did it serve as a stand-in for the discussion of other “apocalyptic” or Malthusian scenarios (environmental disaster, “population bomb,” etc)? Was the book taught and read in explicit relation to the Vietnam War (or as a way of desperately eliding it)?

I don’t know yet who decided that this would make a good high school text book, and I don’t know how it was taught, either in that particular school district or elsewhere in the state. I can probably guess how my grandmother taught it. Have the Russians destroyed the United States? Is there a war on? Is anyone fighting back? Is America still standing? Yes, I can well imagine what my ferociously patriotic, rock-ribbed Republican grandmother would have had to say about those plot twists.

And that’s why I’m not grieved, but truly grateful that she did not live to see this day — not this day, nor the day after.

16 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

“The point of post-apocalyptic fiction is never about surviving the apocalypse; it’s always about reflecting on what kind of society we are, or want to be.”

I was wondering about how a “back to nature” proponent might view these post-moment scenarios. Are there any environmentalist intellectuals/authors who hoped that, by showing individuals surviving essentially on a Paleolithic diet (in a post-apocalyptic landscape) , they could demonstrate to readers via imaginative musings that a world devoid of artificial objects and machines is possible (even if imperfectly realized)?

I haven’t read Alas, Babylon but the Planet of the Apes films, while confirming your point about the commentary on present-day society, similarly seems to allow people a glimpse of the “unthinkable” becoming quite thinkable.

This is a point that film scholar Barbara Creed makes about evolutionary theory: “In his visually arresting writings on evolution, Darwin anticipated the power of the cinema to yoke together disparate forms and to depict visually the drama of evolutionary transformative.”*

*Barbara Creed, Darwin’s Screens: Evolutionary Aesthetics, Time and Sexual Display in the Cinema (Victoria, Australia: Melbourne University Press, 2009), 27.

Mark, thanks for the comment.

The wish fulfillment in Alas, Babylon, like many post-apocalyptic works, is more nostalgic than futuristic. The disaster forces the hero and his little cohort “back to a simpler time” (but not *that* far back, and certainly not permanently). But the whole point of the apocalypticism is to create a (mostly) clean slate in order to remake the social order. It’s not a new Eden though — it’s not even the earth after the Flood, though that’s a closer analogy. This particular book, as well as some others like it, could be read as an errand into the wilderness, really, but an errand that’s only possible if you first re-render the modern world as a wilderness via the deus ex machina of a nuclear strike.

But the book presents a meliorist vision of social change, not a radical vision. Part of the “meliorism” is a “return” to Men Being in Charge of Things and Women Being Grateful for Men’s Leadership and Protection. Oh, and a return to That Time When We Got Along Fine Before Outsiders Tried to Interfere with Race Relations. (So, turn back the clock to some point before Reconstruction?) However, the stronger theme is very much of the 1950s-Superman-PSA variety: discrimination is un-American and we can only win the Cold War if we all find common cause in our shared patriotism. But that’s a very “straight” and uncomplicated reading of the book’s more problematic ideas about race.

Thanks for that interesting Superman link.

I don’t recall hearing very many expressed fears about Trump leading the world into a nuclear Armageddon (I could be wrong).

In contrast to the lower socioeconomic groups, the affluent middle-class possessors of consumer goods during the fifties seemed to be more fearful of atomic annihilation (or, at least, they had more voice through the literary/cinematic channels).

If one substitutes fear of “terrorism” today for nuclear detonations, is there some class distinction that appears designating those who are concerned with terrorism?

Sorry; I know this is veering away somewhat from your original post, but I figured I’d jump on the bandwagon of Robert’s “rambling” confession. . .

No problem.

On Trump and nuclear Armageddon — people were absolutely sounding the klaxon on that. But here we are, a few decades out from the purported end of the Cold War, and the fear of imminent nuclear annihilation just doesn’t scare people like it used to, I guess. I find this astonishing and alarming.

But it’s not “Trump with nukes” that I’m glad my grandmother didn’t live to see, though that’s bad enough; it’s “Russia attacks America, and the Republican party rolls over and plays dead” that I’m glad she’s not here to see. She would blow. a. gasket.

On class distinctions and terrorism fears — I don’t know. Good question.

This reminds me of a British miniseries produced in the 1980s, around the time of “The Day After” titled “Threads.” It’s actually *more* depressing than “The Day After” because it imagines Britain struggling–and utterly failing–to cope with a nuclear war.

Spoiler Alert!

So the final part of the miniseries shows Britain roughly twenty years after the war….and society has fallen apart. The English language itself has been mangled due to the collapse of public schooling. It’s quite depressing. And when I imagine the apocalypse it’s that particular vision that has always struck with me. It offers a stark contrast with “Star Trek,” where World War III is the event in humanity’s history that (along with finally meeting the Vulcans) pushes unity among humans.

That rambling post was to simply say thanks for the intriguing post. So many ways to think about the day after.

“I guess it would be hard to sell a post-apocalyptic novel whose premise was that nobody would survive the apocalypse.” Perhaps the best-known nuclear war novel of the period was Nevil Shute’s On the Beach (1957, film 1959) with exactly that premise.

Yes, I know about On the Beach. Read it in junior high — one of those blessed, life-saving paperbacks on the rack at the back of the classroom that we could use for “free reading.” It would be interesting to compare the sales figures of the two books over time. OTB had the benefit of being first. I’d also be curious to know if it has been assigned more frequently or less frequently in “sophomore English” over the years.

Thanks L.D.

It’s presumed, at least on my part, that post-apocalyptic novels end in some form of dystopian state. I haven’t read any post-apocalyptic novels as you have described here but I have read many dystopian ones, is there a clear distinction between the two genres? Aren’t they both lamenting a bygone era in extreme terms?

Paul, interesting question. It could be that Alas, Babylon! might not really count as a “post-apocalyptic” novel, then, because its ending is not at all dystopian.

Maybe it’s just because I was re-reading Perry Miller last week, but I really am struck by the “errand into the wilderness” theme of this work of fiction, very much reaffirmed/underscored by the novel’s conclusion (which I will not spoil for the reader who may want to zip through the book in an afternoon).

I do think the “optimism” of this novel might explain its place in the curriculum — it’s a feel-good story about America.

At the same time, it seems to me that the “dystopia” in many post-apocalyptic scenarios is actually a perverse form of utopianism. If “hell is other people,” or other kinds of people, the apocalypse can mean a “fresh start.” Maybe not the garden of paradise, but not utter hell either. I’m going to write about this more next time, but, briefly…some (all?) post-apocalyptic fantasies are not really about the people who perished, but about the people who survived. If the loss of life/habitat, however vast, however “tragic,” is necessary to the premise/plot, it may be ultimately incidental to the moral/meaning, which is revealed to/through the survivors. Their future has become the most important future in human history, because it’s the only possible future left. That’s the fantasy/appeal for readers, I think: to be counted among the survivors, to have a shot at the future.

Is post-apocalyptic inherently a secular concept then? Doesn’t it negate the idea of apocalyptic?

Paul, short answer: no, I don’t think so — because after the apocalypse (in some theological systems) comes the millennium. But more on this next time.

But it’s not “Trump with nukes” that I’m glad my grandmother didn’t live to see, though that’s bad enough; it’s “Russia attacks America, and the Republican party rolls over and plays dead” that I’m glad she’s not here to see. She would blow. a. gasket.

It is indeed rather appalling, if unsurprising, that the Republicans are putting partisanship above all else in this respect.

Also perhaps worth mentioning that we have a Pres.-elect who, during one of the debates, seemed unaware of what the U.S. ‘nuclear triad’ is or means, and who is almost certainly unaware of the absurdly excessive size and cost of the current U.S. nuclear arsenal, including about 200 utterly worthless, in military terms, B-61 nuclear ‘gravity’ bombs stationed in certain NATO countries (including a number at Incirlik airbase in Turkey) and currently undergoing a ridiculously expensive and (it goes without saying) unnecessary process of ‘modernization’. (Unnecessary b.c these particular weapons are themselves unnecessary and should be scrapped rather

than ‘modernized’ to the tune of tens of billions of dollars.)

Also the Pres-elect has named a Natl Sec advisor- designate who has dissed Islam (as a whole) and he will have three former generals in key posts (Defense, Homeland Security, Natl Sec Advisor), and while appointing former generals is not in itself necessarily always bad, I would be surprised if any of these three are anything other than supportive of the basic shape of the current nuclear arsenal.

In sum, in 2016, decades after the end of the Cold War and even more decades after The Day After and even more decades after the post-apocalyptic novel that this post discusses, the U.S. still has a nuclear arsenal whose basic strategic premises, such as they are, derive very much from the Cold War (pick your decade, 50s to 80s, doesn’t matter much). The number of warheads has declined over time b/c of various arms limitations agreements with the then-USSR and more recently Russia, but the basic shape of the triad and the strategic premises underlying it have not changed fundamentally since the 1950s. It is in its current configuration hugely expensive and in many respects strategically pointless. Various sober, non-fringe analysts have argued that the entire land-based ICBM leg of the triad is a complete anachronism and should be eliminated — it won’t be, of course.

All this is an indictment of the inertia, folly, and entrenched interests that characterize this part of the military-industrial complex.

[/rant]

P.s. This is all quite separate from the issue of whether Trump is too close etc. to Putin (he is) or whether the Repubs are acting hypocritically and stupidly w/r/t Russian interference in the election (they are).

I see from a glance at the newspaper today that M. McConnell is announcing some kind of intel. cte. investigation of the alleged Russian interference. So Senate Repubs doing nothing was apparently judged politically unwise. It will be interesting to see what, if anything, results.

Thanks for this post. I somehow missed this reading assignment in school. I finished h.s. at the end of the 80s, so maybe I *just* missed it. – TL

Well, I doubt it was a major part of the curriculum anywhere — just shows up here and there on reading lists. It’s definitely a cheerier and more brisk read than On the Beach, which makes it in some ways less commendable but also more understandable as an assigned text. FWIW, at least in CA high schools, students were divided up into “A track” and “B track,” or “college track” and “vocational track” schedules. This book may have been used more often as a reading in one track but not in another.