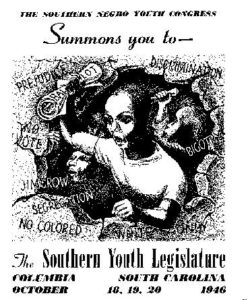

Last week was the seventieth anniversary of a meeting held in Columbia, South Carolina almost forgotten by history. Hosted by the Southern Negro Youth Congress, in October 1946 delegates from all over the world met in Columbia to plan out future strategies for fighting for civil and human rights. Among those who spoke there were W.E.B. DuBois and Paul Robeson. The modern-day celebrations, put together by the University of South Carolina’s Center for Civil Rights, the History Center, and in conjunction with Historically Black Benedict College and the South Carolina Progressive Network, were about “usable pasts” and recovering a nearly-forgotten moment from Southern history. They were also, I found to my satisfaction, about the use of intellectual history in remembering a more radical vision of the past.

David Levering Lewis, the historian and famed biographer of DuBois, gave a speech on October 20, Thursday night, to commemorate the event from seventy years previous. Lewis’ speech, titled “Our Exceptionalist Quagmire: Is There a Way Forward?” was a meditation on American history, American exceptionalism, and the complications categories such as race, gender, and ideology through into comfortable narratives of America’s past. DuBois occupied a place of prominence in Lewis’ speech, a work which put the titan of American thought in conversation with De Tocqueville and John Hector St. John (known before his American naturalization as Michel Guillaume Jean de Crèvecœur), Henry Wallace and Henry Luce. For Lewis, the importance of events like the 1946 Southern Youth Legislature meeting was to offer a different vision of the future—one that was only partially realized by the victories of the Civil Rights Movement. At the same time, Lewis took pains to emphasize how the young men and women of the SNYC were linked to activists across the world, some of them even traveling to London’s 1945 World Youth Congress.

was a meditation on American history, American exceptionalism, and the complications categories such as race, gender, and ideology through into comfortable narratives of America’s past. DuBois occupied a place of prominence in Lewis’ speech, a work which put the titan of American thought in conversation with De Tocqueville and John Hector St. John (known before his American naturalization as Michel Guillaume Jean de Crèvecœur), Henry Wallace and Henry Luce. For Lewis, the importance of events like the 1946 Southern Youth Legislature meeting was to offer a different vision of the future—one that was only partially realized by the victories of the Civil Rights Movement. At the same time, Lewis took pains to emphasize how the young men and women of the SNYC were linked to activists across the world, some of them even traveling to London’s 1945 World Youth Congress.

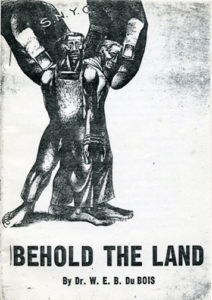

Lewis’ speech put the speech given by W.E.B. DuBois in 1946, titled “Behold the Land,” in an important historical context. DuBois and others on the American Left saw the South as a place where the fight for human rights had to not only be waged, but won. As DuBois himself argued, “The future of the American Negro is in the South.” This was a tacit acknowledgment of the political power of the South in both houses of Congress—no civil or human rights victories could be won without changing conditions on the ground in the states of the former Confederacy. The words brought forth by DuBois in 1946 must have thrilled the delegates. Indeed, one of the great thrills I experienced at the events of the past few days was meeting activists who had the privilege of meeting DuBois in 1946, and carrying on the fight for human rights throughout the dark days of McCarthyism and the Second Red Scare. For them, usable pasts were also important in a different context—the 1946 Southern Youth Legislature meeting featured banners with the images of African American politicians from the Reconstruction era, a stark reminder of the potential of the South to be a more democratic place.

The rest of the week’s symposiums focused on this idea of a usable past. In particular, the events of Saturday, hosted by the South Carolina Progressive Network, put the 1946 SNYC meeting in context of the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement, and in South Carolina’s long history of black struggle. Many attendees there—hearing from U of  SC history professor Bobby Donaldson, along with political scientist Sekou Franklin and Roosevelt University professor of history Erik Gellman—learned of SNYC in the context of an older, and more radical, component of the Civil Rights Movement than most of them were aware of. Most people there expressed astonishment at not knowing much about the history of activism in South Carolina. The sad truth is that figures from South Carolina’s history, such as Modjeska Simkins and John H. McCray, are not as well-known outside the state (or for that matter, even within the state) as they deserve to be. I have written a scholarly article

SC history professor Bobby Donaldson, along with political scientist Sekou Franklin and Roosevelt University professor of history Erik Gellman—learned of SNYC in the context of an older, and more radical, component of the Civil Rights Movement than most of them were aware of. Most people there expressed astonishment at not knowing much about the history of activism in South Carolina. The sad truth is that figures from South Carolina’s history, such as Modjeska Simkins and John H. McCray, are not as well-known outside the state (or for that matter, even within the state) as they deserve to be. I have written a scholarly article

about the importance of South Carolina to the history of civil rights—and why it deserves to be better remembered—but this is a topic that deserves further attention.

When we talk about usable pasts, historians and others should also recognize that we are also talking about the unused past too. Whether it’s activists in 1946 knowing little about the reality of black political power during Reconstruction, or today’s activists only being familiar with the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee, but not the Southern Negro Youth Congress, the past never ceases to be usable by both activists and their antagonists. The last week has been a personal reminder of that long-standing use of history in the public sphere.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I love your point on “usable pasts” presuming the existence of “unused pasts.” It makes me wonder how many usable yet unused pasts are still waiting to be mined, and the awesome responsibility that comes with having the tools to mine them.

Thanks! And you’re exactly right–how do we get at events in the past that haven’t been excavated, so to speak, by historians as of yet? Incredible to think about how much work waits to be done.