As we proceed with our inquiry into the origins of the Epistemic Left, we turn to the journal that most fully embodied the values of left Theory in the United States: Social Text.

[We know, of course, that Social Text is today best-known as the venue within which the Sokal Hoax of 1996 was perpetrated. Suffice it to say, here, that that hoax had comparatively little to do with the first decade of Social Text’s history. In fact, one could exhaustively reconstruct the history of that hoax without saying very much of any value about why Social Text was started or how it functioned prior to the mid-1990s].

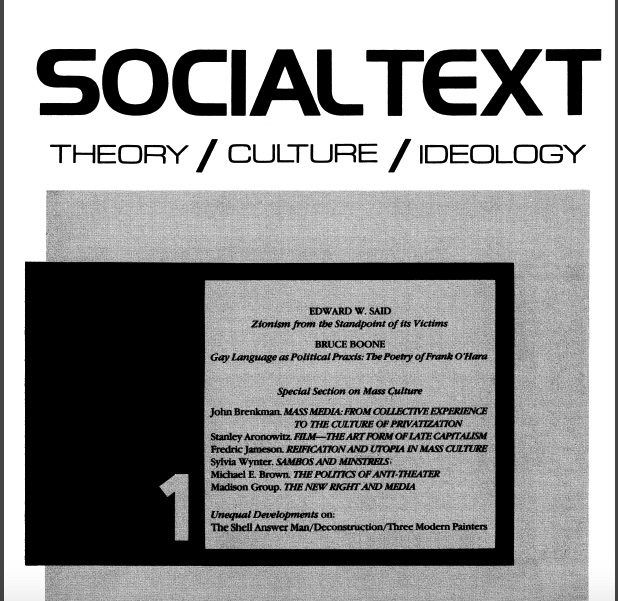

Founded by Stanley Aronowitz, John Brenkman, and Fredric Jameson, and developed in three geographically discrete hubs (Irvine-La Jolla; Madison, Wisconsin; and New Haven, Connecticut), Social Text published its inaugural issue in Winter of 1979.

How did it announce its arrival to the world?

Social Text

framed its mission, broadly, as providing a forum for the consideration of “problems in theory.” (Here, perhaps, is one possible anchor as we seek to define what we mean by “Theory” in our broader inquiry into the history of the Epistemic Left). Social Text’s Prospectus took pains to underline the journal’s “Marxism”: with “Marxism” to be understood “in the broadest sense of the term.”

The unique circumstances of the moment (identified, anticipatorily, as “the 1970s and 80s”) created felicitous conditions for a renewal of historical materialism. Cold War anti-communism no longer colored every consideration of historical materialist thought. Liberalism “had proven itself bankrupt,” while the specialized academic disciplines found themselves in the throes of a thoroughgoing epistemic crisis (“in which traditional methods and presuppositions” had broken down).

Political exigencies had rendered “renewed theoretical investigation of revolutionary possibilities… in the advanced countries” newly urgent. In this light, only the “dialectical framework” of Marxism was adequate to the task of theorizing late twentieth century capitalism.

But Marxism, at the same time, could not be expected to provide all of the answers.

In view of the recent “development of all kinds of theoretical work bearing on culture, sign systems, social relations, power structures, and epistemology––theories which range from semiotics and Lacanian psychoanalysis to information and systems theory, Habermas’s critical pragmatics, Foucault’s political technology of the body, Derrida’s deconstruction, Althusserian structuralism, and Chomskian linguistics”––Social Text would strive to incorporate new ideas and methods while eschewing Theory’s tendency to suppress or repress history. Social Text-ian Marxism would reinvigorate historical materialism by dedicating itself to “dialectical thinking,” resituating texts and practices “in the immense life history of human society from its tribal origins to multinational consumer capitalism and beyond.”

This understanding of critique––the cultivation of a “distinctively Marxist problematic”–hewed closely to that of the classical phase of the Frankfurt School. Social Text would insist upon “the unique dynamics of capitalism as a system that cannot be reversed from within,” attend to “the dominant role of social classes in historical change,” recognize “the primacy of social being over consciousness,” demand “the interrelation of theory and praxis,” and commit to “the necessity of interpreting history in terms of modes of production”: not as “some litany to be repeated but rather define problems and directions of research that need to be worked out afresh and reinvented in terms of today’s situation.” (This language, one senses, must have been contributed by Jameson––he was often critical of Marxist “litanies” that functioned as fetters on free thought).

Analysis would aim at “disclosing the capacity for struggle,” or, conversely, “the tendency toward blockage” in “methodologies and researches.” I think (if I may be allowed to editorialize) that the “methodologies and researches” declension here represents something of a short circuit (or perhaps reflects the perils of writing-by-committee). What was likely meant (I am guessing) was: “we are interested in disclosing the capacity for struggle and/or the tendency toward blockage in a given set of cultural, intellectual, and aesthetic practices.” In any event, Social Text would serve, primarily, as an intellectual home for new kinds of interpretation of phenomena out there in the world rather than as a site of Theorists reflecting Theoretically on Theory itself. (This, I think, is where the actual practice of Social Text deviates farthest from popular perception).

Contemporary capitalism had developed “historically unique forms of repression, integration, and reproduction.” This “new capitalist machine” called for “new modes of critical and utopian thought” and for “new emancipatory impulses” as well as “new forms of struggle.”

Perhaps the most suggestive territory mapped by the Social Text editors was the specification of new areas of interest: 1) “Everyday Life and Revolutionary Praxis”; 2) “The Proliferation of Theories”; 3) “Symbolic Investments of the Political”; 4) “The Texts of History”; 5) “Ideology and Narrative”; 6) “Mass Culture and the Avant-Garde”; 7) “Marxism and the State”; 8) “‘Consumer Society’ and the World System.”

In the next essay, I will explore this eightfold agenda in further detail—here, I think it is worth pausing to consider whether or not this itinerary serves as a guide to the Epistemic Left’s preoccupations in the decades that followed. I invite readers to reflect on this in the comments below.

Works Cited

“Prospectus,” Social Text, No. 1 (Winter, 1979), pp. 1-181.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Came across this passage form Benedict Anderson’s memoirs (Anderson was reflecting both on the rise of Theory within the American academy and his own career as a scholar of Southeast Asia at Cornell):

“…Americans are a practical and pragmatic people, not naturally given to grand theory. A quick glance across the social sciences and humanities for the ‘great theorists’ of the past century makes this abundantly clear, whether in philosophy (Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Derrida, Foucault, Habermas, Levinas, etc.), history (Bloch, Braudel, Hobsbawm, Needham, Elliott), sociology (Mosca, Pareto, Weber, Simmel, Mann), anthropology (Mauss, Lévi-Strauss, Dumont, Malinowski, Evans-Pritchard) or literary studies (Bakhtin, Barthes, de Man, etc.).

All these foundational figures are European.

The grand American exception is Noam Chomsky, who revolutionized the study of linguistics, and, perhaps to a lesser extent, Milton Friedman in economics, though Keynes may last longer.

Of course, this does not mean that contemporary US universities are not obsessed with ‘theory’, only that the ‘theory’ either comes from outside America, is modelled on economics (which has a strong theory-orientation important for understanding the functioning of modern society), or is underpinned by America’s egalitarianism: ‘everyone’, so to speak, ‘can and should be a theorist’, though history shows that individuals genuinely capable of producing original theory are rare.

My own experience as a student at Cornell occurred before ‘political theory’ really took hold. My thesis (1967) could almost have been written in a history department. But by then what was later remembered as the era of ‘behaviourism’, understood as making the study of politics ‘scientific’, was on the rise.

The thirty-five years I spent as a Professor of Government at Cornell taught me two interesting lessons about US academia.

The first was that ‘theory’, mirroring the style of late capitalism, has obsolescence built into it, in the manner of high-end commodities.

In year X students had to read and more or less revere Theory Y, while sharpening their teeth on passé Theory W. Not too many years later, they were told to sharpen their teeth on passé Theory Y, admire Theory Z, and forget about Theory W.

The second lesson was that – with some important exceptions like the work of Barrington Moore, Jr. – the extension of political science to comparative politics tended to proceed, consciously or unconsciously, on the basis of the US example: one measured how far other countries were progressing in approximating America’s liberty, respect for law, economic development, democracy, etc. Hence the rapid rise, and equally rapid fall, of an approach that today looks pretty ‘dead’ – modernization theory.

Needless to say, there was often an openly stated Cold War objective behind this kind of theory. Namely, to prove that Marxism was fundamentally wrong! In its innocence, this kind of ‘look at me’ theory typically ignored such embarrassing things as the very high rates of murder and divorce in the US, its hugely disproportionate Black prison population, persistent illiteracy and significant levels of political corruption, and so on.”

That’s an interesting passage from B. Anderson.

Couple of quick, off-the-cuff reactions.

First, to this:

“…Americans are a practical and pragmatic people, not naturally given to grand theory. A quick glance across the social sciences and humanities for the ‘great theorists’ of the past century makes this abundantly clear, whether in philosophy (Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Derrida, Foucault, Habermas, Levinas, etc.), history (Bloch, Braudel, Hobsbawm, Needham, Elliott), sociology (Mosca, Pareto, Weber, Simmel, Mann), anthropology (Mauss, Lévi-Strauss, Dumont, Malinowski, Evans-Pritchard) or literary studies (Bakhtin, Barthes, de Man, etc.).”

If talking about ‘grand theory’ as a kind of style or theoretical ambition, probably at least a couple of Americans in addition to Chomsky should make the list, for instance Talcott Parsons; doesn’t mean one has to like his work or find it appealing or insightful etc., and I’m sure Anderson didn’t, but that’s not immediately pertinent. [Mills amusingly criticized Parsons’ writing style (among other things) in ‘The Sociological Imagination’, but Parsons is a major figure in 20th-cent. sociological theory.]

Second, on modernization theory:

Yes it was tied to the Cold War and often, consciously or otherwise, took the U.S. (or Western democracy) as the standard. It never really completely disappeared though, so much as changed shape and packaging.

Once shorn of its exhorting (“be more like us!”), what emerges in recent decades is, e.g., studies of changes in ‘values’ across the world (Ronald Inglehart) or how governments are increasingly expected to do similar kinds of things (John Meyer et al.), or even a fair chunk of the globalization literature, all of which probably owe some kind of debt, in one way or another, to modernization theory of the immediate postwar decades. (Again, not evaluating this work, just noting its existence.)

p.s. Sociological theory isn’t my field, but as long as I bothered to write the above comment I should prob. add something before shutting off the computer for a while. Mills was right about Parsons’ writing style, but he probably overstated a bit his case vs. ‘grand theory’ in The Sociological Imagination. E.g., p.33:

“The basic cause of grand theory is the initial choice of a level of thinking so general that its practitioners cannot logically get down to observation. They never, as grand theorists, get down from the higher generalities to problems in their historical and structural contexts…. One resulting characteristic is a seemingly arbitrary…elaboration of distinctions….”

This no doubt accurately described some stuff in vogue in American sociology in the ’50s (when the passage was written), but I think it’s not *completely* fair as applied to Parsons himself. And definitely would not apply to, say, Foucault (though Mills died before Foucault’s work started to be generally known in the U.S., and indeed before a lot of it was written).

Kurt, I can’t tell you how much I am enjoying this series of posts! (I left a belated comment to the post on Said, I hope you noticed it).

The role of Marxism in the trajectory of Social Text is a fascinating subject; my impression is that as a whole the journal progressively distanced itself in the 80s and especially the 90s from a Marxist–orthodox or heterodox–perspective, if we define this at the very least as the practice of a dialectics that does not abandon the issue of class and socioeconomic struggle. Some would argue that in engaging Gramsci, Althusser, Raymond Williams, Stuart Hall, and other Marxist or Marxist-inspired thinkers most of this critical work was working within the spirit of Marxism, even if class or dialectics did not figure in any way whatsoever in their “methodologies and researches.” As I read texts in graduate school, I always wondered about this matter, what did it mean for example that folks who participated in the Marxist Literary Gorup at the MLA were not engaging class difference in their work–forget dialectics. In this regard, the impact of Foucault and his theorization of “power” cannot be undervalued, nor Laclau and Mouffe’s so-called post-Marxism resignification of Gramscian hegemony (both would be critiqued, along with Zizek, by Marxist critics for their idealism and how in different ways this line of work seemed to abandon the issue of class–even with the resurgence of Marxist theory in the past few years one can still perceive this in how folks–both scholars and activists–speak in terms of oppression, without alluding in any way to exploitation). But even from the beginning, one might ask, how loosely and broadly can we define Marxism before it becomes, well, not Marxism at all?

One element that I found interessting in the Social Text editorial is the use of “new”: it comes up repeatedly, as if there was an anxiety about not repeating certain theoretical traditions (aside from liberalism, perhaps orthodox Marxism?). Coupled with Anderson’s comment about how theory–that “mirroring the style of late capitalism, has obsolescence built into it, in the manner of high-end commodities.”–I can’t help but think again about how institutions themselves drive scholarly work to always be trendy and, yes, fashionable. I see this also as an operative attitude among some scholars in my field, who dismiss a priori any work that is seen as not dealing with “new” theories–tragically, this kind of logic has been used to marginalize work dealing with gender and sexuality, as if to suggest that since there was already a high moment of feminist and queer theory, we should not engage with these matters anymore. I can’t help but ask myself what extent the innovations featured in the pages of Social Text were not fueled in this manner?