There’s no better primary source for illuminating the intellectual, cultural, political, and economic life of Philadelphia in the mid-18th century than an issue – any

issue — of Ben Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette. It doesn’t much matter which number you pick – there are more telling details about life in that prosperous, bustling, contentious, connected colonial world in one printing of that newspaper than it would be possible to explore, or even to “cover,” in a week’s worth of lectures or course discussions.

For class a couple of weeks ago, I picked a number at random from Franklin’s paper and used that to anchor a discussion that also served as an orientation to the primary source analysis paper my university students will be writing. I had already planned to include excerpts from the May 9, 1754 number (with the famous “Join or Die” cartoon) in my lecture slides for that night. But to introduce the idea of “close reading” a primary source, particularly a newspaper, I wanted to have students discuss a “non-momentous” number – just “a day in the life” of Ben Franklin’s town.

For this exercise, I do like to use earlier numbers, since they are printed in three columns rather than four – that makes photocopied handouts more legible for students. So after some browsing in the Early American Newspapers

database, I settled on the number from Nov. 18, 1742. For discussion, I divided the class into six large-ish sections – one section per column for the last two pages of the newspaper. I told them that our task would be to try to characterize mid-century Philadelphia life and culture based on what we found in this paper: with the telling details included in one single number of Ben Franklin’s Gazette, what story could we tell about daily life in and around that city? So I gave them about 15-20 minutes to get into smaller groups and go through the ads in their assigned column, noting in the margins what aspect(s) of colonial life – religion, politics, economy, culture, education, etc, etc – each particular advertisement could illuminate. And then we discussed our findings together.

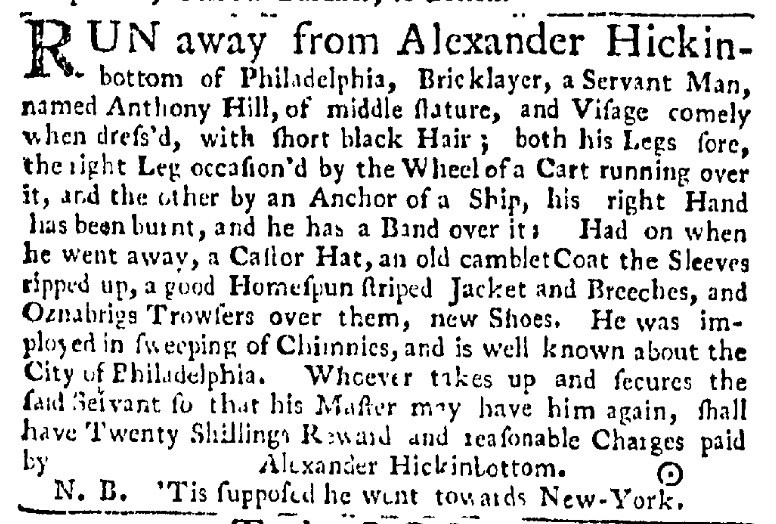

Of all the ads the students singled out, perhaps the most striking text for them (and for me too) was a notice placed by a bricklayer seeking the return of his indentured servant:

Run away from Alexander Hickinbottom of Philadelphia, Bricklayer, a Servant Man, named Anthony Hill, of middle stature, and Visage comely when dress’d, with short black Hair; both his Legs sore, the right Leg occasion’d by the Wheel of a Cart running over it, and the other by an Anchor of a Ship, his right Hand has been burnt, and he has a Band over it. Had on when he went away, a Castor Hat, an old camblet Coat the Sleeves ripped up, a good Homespun striped Jacket and Breeches, and Oznabrigs Trowsers over them, new Shoes. He was imployed in sweeping of Chimnies, and is well known about the City of Philadelphia. Whoever takes up and secures the said servant so that his Master may have him again, shall have Twenty Shillings Reward and reasonable Charges paid by Alexander Hickinbottom.

N.B. ‘Tis supposed he went towards New-York.

Lord have mercy – where do you even begin? The extraordinary details about this poor fellow Anthony’s many injuries were so extreme that they were almost comical. Almost. The guy had a cart run over one leg, a ship’s anchor dropped on the other, and his hand burned — all in (one presumes) three separate work-related accidents. Perhaps no single text I’ve read better conveys in a shorter space the punishing and perilous working conditions of the manual laborers. This poor man may have had a comely face, but the rest of his body was shattered by the danger and difficulty of his work.

He was broken, he was burned, he was ragged, with a patched coat and rough cloth trousers. But he did have a decent pair of britches and a jacket to match. And, most importantly, he had a new pair of shoes. We decided that our friend Anthony probably waited until he got his annual pair of shoes from his tightwad tormentor of a master, and as soon as he got those new shoes, he hit the road.

“‘Tis supposed,” the ad says, “he went towards New York.”

We were all rooting for him, hoping that somehow, against all odds, he made it to New York and found some place to go, or at least to lie low, where his body wouldn’t be bruised and broken again either in service to another man or in pursuit of his daily bread. One could almost imagine a whole series of stories about how poor Anthony’s awful fortunes finally turned. But those would be tall tales indeed, an unlikely end to what was perhaps an all-too-typical life of peril and pain.

We were all rooting for him, hoping that somehow, against all odds, he made it to New York and found some place to go, or at least to lie low, where his body wouldn’t be bruised and broken again either in service to another man or in pursuit of his daily bread. One could almost imagine a whole series of stories about how poor Anthony’s awful fortunes finally turned. But those would be tall tales indeed, an unlikely end to what was perhaps an all-too-typical life of peril and pain.

I was curious to find out if anyone else has found out what became of Anthony. I have done some preliminary searching, but have yet to find any clues to Anthony’s eventual fate. And that’s no surprise. This was a poor, common laborer, possibly illiterate, probably in horrible health, far more likely to be marked than to make his mark.

However, I did find a journal article that points to the broken body of Anthony Hill as one of many examples of the harsh labor conditions endured by those on the bottom rungs of the economic / class ladder in Philadelphia. “In the most basic of terms,” Michael Bradley McCoy writes of Hill’s situation, “life as a servant was a dangerous and demeaning prospect.”*

Indeed, that’s pretty much all we know of Anthony Hill. We know that, and we know that he seized his chance and tried to put a lot of miles on that new pair of shoes.

‘Tis supposed he went towards New York?

Well then: go, Anthony, go!

__________________________

*See Michael Bradley McCoy, “Absconding Servants, Anxious Germans, and Angry Sailors: Working People and the Making of the Philadelphia Election Riot of 1742,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 74, no. 4 (Autumn 2007): 427-451. (For those who do not have access to JSTOR, it looks like Penn State has made a .pdf of the article available here

.)

0