Guest Post by Mike O’Connor

By most metrics, the success of Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94) dwarfed that which its predecessor Star Trek had received on NBC during its initial 1966-69 run. While the first show had to be rescued from cancellation after its second season by a viewer letter-writing campaign, its successor ran for seven years with solid ratings. Star Trek: The Next Generation (TNG) substantially enlarged the core audience for Star Trek and eventually its characters and time-frame replaced those from the original series as the focus of the feature films. (Since then, the movies have come to feature younger actors playing the characters from the original series.) Yet TNG had a mission beyond delivering ratings and making money for its studio. Star Trek was more than a television show: it embodied a particular philosophy that was one of central aspects of its appeal. Gene Roddenberry, the auteur behind Star Trek who is widely credited for supplying the “vision” that characterized the Star Trek universe, described the show as his “statement to the world” his “political philosophy,” and his “overview on life and the human condition.”[i] (Roddenberry created TNG and worked on its first few seasons. His declining health and increasingly erratic personal behavior led to him being eased out of positions of authority before his death in 1991. The extent to which Roddenberry was personally influential on the vision of Star Trek: The Next Generation is a subject for debate; but the larger significance of his philosophical and ideological blueprint is beyond question.) Media scholar Henry Jenkins explained that the new series “had to carefully negotiate between the need to maintain continuity with the original series (in order to preserve the core Star Trek audience) and the need to rethink and update those conventions (in order to maintain the programme’s relevance with contemporary viewers and to expand its following).”[ii] Philosophically, this meant that the later show had to distinguish between those ideas that were central to the ethos of Star Trek and those that needed to be modified or even abandoned to keep up with the spirit of the times.

Both Star Trek series chronicled the adventures of a group of interstellar space travelers living centuries from now. The heroes serve aboard the U.S.S. Enterprise, a vessel in the “Starfleet” of the United Federation of Planets. “The Federation” is a governing body of planetary representatives, of which Earth is a central member. Starfleet has dispatched the Enterprise to the furthest reaches of the galaxy with arguably conflicting tasks: on one hand the crew is involved in exploration and scientific research, and on the other, it serves  as the Federation’s military and diplomatic representative far from the centers of power. As a result, the ships’ crews are constantly brought into contact with ideas and practices that are different from theirs; some situations are learning opportunities, while others invite danger and require force. One way or another, civilizations bump into one another in Star Trek series. In many cases, such as the planets that came together in order to form the Federation, the results are of benefit to all. Other situations, however, invite conflict: cultural, intellectual, political and—occasionally—military.

as the Federation’s military and diplomatic representative far from the centers of power. As a result, the ships’ crews are constantly brought into contact with ideas and practices that are different from theirs; some situations are learning opportunities, while others invite danger and require force. One way or another, civilizations bump into one another in Star Trek series. In many cases, such as the planets that came together in order to form the Federation, the results are of benefit to all. Other situations, however, invite conflict: cultural, intellectual, political and—occasionally—military.

Typically, these conflicts are resolved by some action taken by the captain of the ship. That position was filled in TOS by James T. Kirk, played by William Shatner, while Patrick Stewart’s Jean-Luc Picard sat in the big chair in the later series. David Gerrold, a writer who worked on both shows, wrote in 1973 that when Star Trek was at its best, the captain’s decisions were the focus of the episode. Plotlines that placed their characters in some sort of a trap and then spent the rest of the episode freeing them are “the easy story to tell. If Star Trek had been a truly dramatic series, then the essential Star Trek story would not have had to have been ‘Kirk in Danger,’ but ‘Kirk Has a Decision to Make.’ The decision is the core of every dramatic episode.”[iii] The particular nature of Star Trek’s format meant that these dramatic decisions frequently offered a fairly strong stance about some moral or political issue. But different problems and concerns characterized the time periods in which each series was produced. TOS and TNG shared the Star Trek name, but each series developed its own characteristic viewpoint.

Among the different arenas in which Star Trek articulated an opinion, central among these was the political one. I have argued elsewhere that TOS was a fundamentally liberal project, but that 21st century understandings of that doctrine cannot be read backward to apply to a 1960s television show. The first series embodied a creative tension between the Cold War liberalism and countercultural anti-militarism that competed to define late ‘60s liberalism.[iv] For the producers of TNG, “updating” those views in response to a world with different issues and new preoccupations was not an easy task. Roddenberry himself claimed that TNG represented “the product of [his] mature thought,”[v] but the relationship between TOS and TNG is not best understood as that of draft to final copy. Instead, I would suggest that Star Trek: The Next Generation represents the continuing articulation of liberal values as those values themselves were changing.

By 1987, the Reagan Revolution was in full swing. Cold War liberalism was no longer an “establishment” philosophy. As a response to Reagan’s escalation of the Cold War and willingness to back repressive anticommunist governments abroad, countercultural pacifism still existed. Yet it was rather marginal in its import, at least compared to its Vietnam-era heyday. Many Democratic politicians had abandoned the Great Society ideals of economic redistribution and confronting various forms of discrimination. These priorities, they believed, were unattractive to what they viewed as a more conservative electorate. The office-seeker who embodied this strategy most successfully was Bill Clinton, a “new Democrat” who promised to leave behind much of his party’s purportedly outmoded philosophical and political commitments. Clinton was elected president in 1992, in the middle of TNG’s television run.

American liberals and leftists who felt that the Democratic Party had abandoned them despaired of seizing the levers of power anytime soon. Thus one of the most important expressions of late-twentieth century American liberalism became its theoretical and intellectual wing. And what many liberal intellectuals were advocating was some form of cultural relativism. This term denotes a somewhat vague idea that highlights common features of several more comprehensive theories. Proceeding from the anthropologically established fact that values vary widely across cultures, relativists maintain that the only authority that moral and political distinctions can have is derived from their status as cultural standard-bearers. Therefore outside of their culture of origin, rules have no binding quality whatsoever. The theory itself is at least as old as the ancient Greek sophist Protagoras and his famous claim that “man [sic] is the measure of all things” but it enjoyed a renewed popularity in the academy in the late 20th century. Many of the most prominent waves of scholarship during this period, such as deconstructionism, post-structuralism, “third wave” feminism and neo-Pragmatism, articulate, assume or at least grapple with a relativist program.

By the time that Star Trek: The Next Generation premiered in 1987, cultural relativism had firmly implanted itself in at least a segment of the American population. By the late ‘80s the Civil Rights movement and Black Power had run their course. Voices for racial justice often spoke the language of identity politics, which focused on respecting the differences between cultures rather than appealing to universal standards of justice. After his Discipline and Punish was published in 1975, Michel Foucault’s relativistic arguments became so influential that he became, in the words of historian Andrew Hartman “the most widely read theorist in American humanities since the sixties.”[vi] In 1986, Carol Gilligan argued in In A Different Voice that women and men possess different and incommensurable moral faculties. That same year, the authors of Women’s Ways of Knowing offered a parallel argument for a female epistemology. Though nearly all of these writers denied that they actually were relativists in a naïve or vulgar sense, the doctrine increasingly came to underwrite liberal thought. Additionally, relativist ideas were finding expression in the language of non-intellectuals. In 1986, philosopher Stephen Satris called the attitude of “student relativism” one of the “most serious, pervasive and frustrating problems facing philosophy teachers today.” Students faced with a professor asking whether such time-honored values as “rationality,” “love” or an “examined life” were a necessary component of human flourishing will simply “fly the flag of relativism” by responding, “Who’s to say?”[vii]

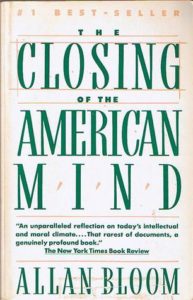

The rising influence of relativism was not welcomed in all corners. The same year that TNG premiered, Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind climbed the best-seller lists. For Bloom, cultural relativism had completely taken hold of the college-age youth of the country, and its effects struck at the core of the western tradition itself. Firmly entrenching itself since the 1960s, argued Bloom, “relativism has extinguished…the search for a good life.”[viii] The idea that objective standards of discourse were being  undermined by the incessant demands of women and minority groups to pay them linguistic respect spread throughout the country as the specter of “political correctness.” A host of other authors jumped on Bloom’s bandwagon, including William Bennett, Dinesh D’Souza and Roger Kimball. Whether or not Bloom, et al., were correct about the horrible damage that relativism was doing to our civilization, they were right at least about the fact that relativism was catching on as a prominent ethical discourse among the educated left.

undermined by the incessant demands of women and minority groups to pay them linguistic respect spread throughout the country as the specter of “political correctness.” A host of other authors jumped on Bloom’s bandwagon, including William Bennett, Dinesh D’Souza and Roger Kimball. Whether or not Bloom, et al., were correct about the horrible damage that relativism was doing to our civilization, they were right at least about the fact that relativism was catching on as a prominent ethical discourse among the educated left.

To the extent that relativism offered a dividing line between left and right, Star Trek: The Next Generation was clearly on the left. In championing the new form that liberal values were now taking, however, it sometimes found itself at odds with its predecessor series. The clearest example of this new direction involves stories that featured the Prime Directive. This is the highest of the Federation’s laws, and it says that those who serve on Starfleet vessels cannot interfere in the affairs or the development of a less technologically advanced culture. In the earlier series, this was typically justified by some reference to the human need for self-determination in order to flourish. What that meant in a practical matter is that, in TOS, Captain Kirk frequently broke it. When he did so, however, he justified his actions by some standard of self-determination which he believed to be objective. That is, if Kirk believed that interfering would make people more free rather than less, he would interfere. His attitude on these matters, then, reflected a form of the traditional liberal humanism that one might associate with Locke or Rousseau. In this context, however, liberal humanism can seriously run the risk of confusing one’s own local values with the universal human standards that are supposed to characterize freedom. That is the essential conflict in the liberal humanist project, one which can embody a healthy and creative tension. But by the time of TNG this tension had been resolved so that the ideal of non-interference simply no longer referred to humanistic flourishing. Instead, it was about cultural integrity. As a result, the Prime Directive embodied a commitment to cultural sensitivity rather than to liberty. The fundamental values of the Federation were no longer rooted in the liberal humanistic claim that every people has its own right to self-determination and autonomy. Instead, they were now based on the claim that there is no Archimedean point from which to make value judgments.

In the TNG episode “Symbiosis,” for example, the crew encounters two cultures, the Ornarans and the Brekkians. The latter planet owes its entire economy to the production of an addictive drug for the former. The Ornarans believe that the drug is medicine for a deadly disease, but the Enterprise’s Dr. Crusher discovers they have not had the disease in generations, and now the drug only saves them from the effects of the withdrawal symptoms. Crusher claims that this is a case of exploitation of one group by another. Picard’s only response is, “That’s how you see it.” He does not claim that he sees it some other way, for presumably he does not. In this sense, his response is very similar to the “Who’s to say?” of Satris’s philosophy students. Instead, the fact that the values of the two planets’ inhabitants may differ from those of the Federation is sufficient to demonstrate to Picard the immorality of even telling the Ornarans of what he has learned.

In the episode “Half A Life,” Lwaxana Troi, mother of ship’s counselor Deanna Troi, meets and falls in love with Timicin, a man from the planet Kaelon II, which orbits a dying sun. Timicin is a scientist, the one who is closest to the solution to the problems that plague his planet. Unfortunately, Timicin turns 60 in a few days, and his people undergo a ritual suicide as they reach that age. Lwaxana begs Picard to intervene, but he insists that “the Prime Directive forbids us to interfere with the social order of any planet.”

After trying, and failing, to convince Timicin to abandon his culture by refusing to participate in the ritual (called the Resolution), Lwaxana and Deanna are discussing the situation.

Lwaxana: I’ve never considered how deeply ingrained this Resolution ritual is.

Deanna: Ritual provides structure, both good ones and bad ones.

Lwaxana: Well this is a bad one.

Deanna: Your point of view.

Characters in The Next Generation routinely point out that each other’s opinions are, in fact, their opinions. This somewhat cloying observation is tossed around as though it trumps any possible moral position. This is because, from a relativist perspective, it does. Even Timicin’s daughter, who is upset that she can’t watch her father die, takes the moral high ground with Lwaxana by asserting that the latter is culturally insensitive. “How dare you criticize my way of life and my beliefs?”

In another episode, “Who Watches the Watchers?,” the crew is assigned to repair an anthropologist’s station on the planet Mintaka. Their high-tech “duck blind” renders the scientists invisible so that they can conduct anthropological research without the planet’s inhabitants knowing that they are there. During the repair, two Mintakans see the duck blind. In the process of investigating it, one accidentally hurts himself quite badly. Crusher brings him up to the ship for medical care, and Picard is not happy about it.

Crusher: Before you start quoting me the Prime Directive—he’d already seen us, the damage was done. It was either bring him aboard or let him die.

Picard: [Forcefully] Then why didn’t you let him die?

Crusher: Because we were responsible for his injuries.

Picard: I’m not sure that I concur with that reasoning, Doctor.

Here Picard, the decision-maker on Enterprise D, makes it clear that the maintenance of a culture’s integrity is more morally important than the rights of the individual to his/her own life, or even to more commonsensical notions of fair play.

But the show does not take a consistent relativist line. “Justice” finds the crew on a planet whose inhabitants, the Edo, only punish randomly selected crimes. For any transgression, however, the penalty is death. When Doctor Crusher’s son, Wesley, is unlucky enough to be in a “punishment zone” when he breaks a window, the full weight of the law comes down upon him. Picard tries to convince the Edo to return the boy to him, but at every turn they best the captain in moral argument. They point out that they did not ask the crew to come to their planet, that their society is based on respect for the law, and that they have no crime precisely because their laws are so strict. They even become resentful when Picard tells them that his society no longer uses the death penalty, as they take him to be passing judgment on their “primitive” ways.

Ultimately Picard decides that he simply cannot allow a member of his crew to die under these circumstances, and he removes Wesley from jail with his superior technology. The reasoning that supports such an action is inconsistent and problematic. Starfleet is a dangerous business, and crew members die on missions with some frequency. Picard is willing to sacrifice those under his command for the goals of his mission; what he is presumably not willing to do is allow his crew member to die for an offense that he views as trivial. In this case, at least, Picard appears to take the line that Wesley’s right to life is more important than the Edo’s right to live by their own values. The idea that the Edo respect for order may in fact be a better way to organize society than his own emphasis on individuality appears to play no role in his decision making.

Thus the Prime Directive, which could be a troubling but ultimately self-congratulatory nuisance for liberal humanist Kirk, is a site of serious tension if not hypocrisy for Picard. Mike Hertenstein has written that “on The Next Generation, the PD [Prime Directive] was observed more strictly. That is to say, it was given more sophisticated lip service…Yes, Captain Picard will break the PD,…but not without soul-searching and hand-wringing.”[ix] On my reading, however, the issue is more challenging than that. The philosophy of cultural relativism has little relevance when the vast majority of people that you meet belong to the same culture. Few of us in the viewing audience have the opportunity to decide whether we should impose our moral views on a people who do not share them. Picard, in his fictional Star Trek universe, actually has to put this doctrine to the test. Thus his problems are like a laboratory experiment in cultural relativism.

To my mind, this experiment reveals two interesting results. The first is that telling a satisfying story with a relativist moral is a difficult, if not impossible, task. If the truly noble thing to do is never interfere or impose, then a television episode trying to advocate such a course of action will consist of forty-four minutes of our heroes debating and analyzing a situation before ultimately doing nothing at all. In the episode “Symbiosis,” discussed above, Picard ultimately decides not to tell the Ornarans that they are addicted to the Brekkians’ drug. But he also decisively refuses to help them repair their ship, which he had earlier promised to do. By not repairing the ship, Picard is both refusing to interfere and at the same time helping the Ornarans to realize their situation—without a ship they will not be able to obtain the drugs they so desperately desire. This episode does allow Picard to decisively and actively do nothing, but in general a plot resolution that involves no decision or action makes for rather uninteresting television.

The second result of the narrative experiment in cultural relativism is perhaps more important. That is that neither TNG nor, presumably, its viewers are entirely comfortable with its relativistic bent. Relativism is primarily a reaction against ethnocentrism, but not all desires to interfere with another culture have such unworthy motives. In the episode, “Pen Pals,” for example, the Enterprise’s helmsman Data has been chatting via a sort of interstellar “ham radio” with a little girl who lives on a remote planet. Natural events are causing the girl’s planet to disintegrate. When Data asks Picard to use the ship to save the planet, the captain takes the position that rescuing a group from a natural disaster without their knowledge leads down the slippery slope toward cultural imperialism. During the ensuing conversation between several Enterprise officers, each offers a slightly different take on what the ship should do. One even calls the prime directive “callous and cowardly” in this instance. Picard, claiming that one of the functions of the Prime Directive is to “protect us from our emotions,” finally decides that the ship will take no action to save the planet. At the very last minute, however, the captain overhears a transmission from Data’s friend. He is emotionally moved and changes his mind. This is hardly a surprise: it is difficult if not impossible to imagine an American prime-time television series in which the heroes would simply proceed on their way when they had the opportunity to save billions of people with little trouble to themselves. But it is nonetheless inconsistent. If liberal humanism runs the risk of an arrogant cultural imperialism, cultural relativism can lead to a shocking lack of concern for the welfare of individuals. TNG sees these problems, but does not offer a solution with any real confidence.

Because Star Trek: The Next Generation deals with problems that relativism raises, but does not have a compelling answer for them, many plot resolutions are rather wishy-washy. Even “Pen Pals” is not willing to take a clear stand on the issue it raises. At the very end of the episode, Picard orders that Data’s friend’s memory be wiped of any knowledge of the Enterprise, through a scientific technique that had not been mentioned up to the point in which it is used. If no one on the planet has any knowledge that Picard’s ship was ever there, then in a sense the crew did not interfere. The captain can have his relativist cake and eat it, too.

Hertenstein has pointed out the prevalence of these deus ex machina endings, whereby a seemingly difficult moral choice is rendered unnecessary or inconsequential by a sudden turn of events. Yet even he fails to notice that the vast majority of his own examples come from TNG rather than TOS. In the episode “Justice,” discussed earlier, Picard takes Wesley from the Edo, but ultimately has to deal with their technologically superior “god” who is orbiting the planet. The god threatens to destroy Picard for interfering with the Edo, but Picard argues from a decidedly non-relativist position that “there can be no justice so  long as laws are absolute.” It is the god, rather than the Edo themselves, that is the true arbiter of Edo morals. Thus its approval of Picard’s action suggests that, in this case, the relativist and humanist projects yield the same result. But the audience is deprived of an answer to the really interesting question, the one that Gerrold says should define a dramatic episode. What people really want to know is “What would Picard have decided if he had to choose between violating the Prime Directive and allowing Wesley to die?” In this case, Picard is allowed to violate the Prime Directive but have his action blessed by the culture whose mores were fundamentally disrespected. Like “Pen Pals,” this episode slinks out of Picard having to take a stand on what values are most central to him.

long as laws are absolute.” It is the god, rather than the Edo themselves, that is the true arbiter of Edo morals. Thus its approval of Picard’s action suggests that, in this case, the relativist and humanist projects yield the same result. But the audience is deprived of an answer to the really interesting question, the one that Gerrold says should define a dramatic episode. What people really want to know is “What would Picard have decided if he had to choose between violating the Prime Directive and allowing Wesley to die?” In this case, Picard is allowed to violate the Prime Directive but have his action blessed by the culture whose mores were fundamentally disrespected. Like “Pen Pals,” this episode slinks out of Picard having to take a stand on what values are most central to him.

Philosopher Richard Rorty observed that “the novel, the movie and the TV program have, gradually but steadily, replaced the sermon and the treatise as the principle vehicles of moral change and progress.”[x] It is through these fictional forms, he argued, that we describe the kinds of pain we inflict on one another. Armed with this knowledge, we can hopefully begin to eliminate them. If Rorty is correct, then the inability of Star Trek: The Next Generation to tell a compelling story with a cultural relativist message is of more than merely academic interest. It suggests that relativism as a comprehensive ethical system may never achieve more than a parasitical check on the tendencies toward ethnocentrism to which liberal humanism is always subject. This is still a significant contribution, one that should not be minimized. But the example of TNG also has a message for American political liberalism. Democratic politics is about the swaying of hearts and minds, and central to this endeavor is the ability to tell resonant, meaningful stories. The show’s difficulty in articulating a consistent relativist position suggests that the extent to which the liberal political project is animated by this doctrine is the extent to which it is unlikely to succeed.

Mike O’Connor is a candidate for the Master of Public Affairs at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. He has published the article “Liberals in Space: The 1960s Politics of Star Trek” in the journal The Sixties and is the author of A Commercial Republic: America’s Enduing Debate over Democratic Capitalism. He can be found online at eight-hundred-words.net

[i] Alexander, David. “The Humanist Interview: Gene Roddenberry—Writer, Producer, Philosopher, Humanist.” The Humanist, March/April 1991: 5-38, 14. (Excerpts from the interview are available here.)

[ii] Jenkins, Henry, “Genre and Authorship in Star Trek,” Science Fiction Audiences: Watching Doctor Who and Star Trek, ed. Henry Jenkins and John Tulloch (New York: Routledge, 1995), 175-95.

[iii] Gerrold, David, The World of Star Trek (New York: Ballantine Books, 1979), 232.

[iv] O’Connor, Mike, “Liberals in Space: The 1960s Politics of Star Trek,” The Sixties (New York, Routledge, 2012), 5:2, 185-203. (Also available here.)

[v] Alexander, 21

[vi] Hartman, Andrew, A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars (Chicago, University of Chicago Press: 2015), 3

[vii] Satris, Stephen A., “Student Relativism,” Teaching Philosophy (Philosophy Documentation Center (Philosophy Documentation Center, September 1986), 9:3, 193-205, 193-4

[viii] Bloom, Allan, The Closing of the American Mind (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987) 34.

[ix] Hertenstein, Mike, The Double Vision of Star Trek: Half Humans, Evil Twins and Science Fiction (Chicago: Cornerstone Press, 1998), 121.

[x] Rorty, Richard. “Introduction.” Contingency, Irony and Solidarity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), xvi

3 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I do not agree with the conclusion though the preceding analysis is adept. The conclusion surprisingly fails to respond to a central claim of Rorty’s relativism: that the author thinks we cannot tell a “satisfying” or “compelling” story about cultural relativism suggests a lack of fit between compellingness and relativism that could be the fault of compellingness rather than the fault of relativism. Drop the idea that there is something wrong with an episode that leaves you without an easy answer that seems to flow inexorably from first principles, as relativists would often have us do, and you will find the episodes perfectly compelling. That is, Rorty didn’t think that narratives had to tell us “the answer” to serve a valuable edificative role. Or to put it another way, the enduring popularity of tNG with many people tells us that their sense of compellingness fits the show’s kind of relativism pretty well.

It’s a fair point that people will disagree about what constitutes a “compelling” story. But I did not mean to suggest that whatever a narrative can be called “satisfying” is dependent on its articulation of “an easy answer that seems to flow inexorably from first principles.” That would indeed be rather silly. Instead, I suggested that the first principles that TNG actually does invoke fairly consistently are rarely carried to their logical conclusions, even when the narrative of a particular episode sets up what seems to be an unavoidable decision. I find deus ex machina climaxes to be very common in the episodes of TNG that feature the Prime Directive. I personally find this narratively unsatisfying, and thought that others would too. To the extent that I am mistaken about that, it is indeed a flaw in the argument.

Hey, I can probably donate some paragraph breaks if you need a few